Black is the universal colour of protest against oppression. Black is the colour of tyranny. Black is the colour of evil. So when on13 February 1986, Iqbal Bano, the famous Pakistani ghazal singer, decided to wear a sari banned as a non-Islamic outfit by the dictator, General Zia-ul- Haq, who had already Islamized Pakistan, the colour of the sari could not have been anything other than black. It was aorn to protest aganst his tyranny. And when the singer clad in black started singing to a packed hall of 50,000 people in Lahore’s Alhamra Arts Council, the atmosphere became electrifying.

As she sang Faiz Ahmed Faiz’s famous revolutionary song, Hum dekhenge /Lazim hai ke hum bhi dekhenge / Wo din ke jis ka wada hai/ Jo lauh-e-azl mein likha hai (We shall certainly witness the day that has been promised to us, and written on the pages of eternity), the crowd erupted in a bout of thunderous applause. There were workers from political parties, peasants, trade union activists, students, teachers, men and women from all walks of life, who were being repressed by the dictator and deprived of their right to protest.

Advertisement

She continued, Jab zulm-ositam ke koh-e-garan/Rooi ki tarah ur jaenge/Hum mehkoomon ke paaon tale/Ye dharti dhar dhar dharkegi/ Aur ahl-e-hakam ke sar oopar /Jab bijli kar kar karkegi/ hum dekhenge (When these high mountains of tyranny and oppression will start blowing away like fluff, when this earth will tremble underneath our feet, when lighting will strike the heads of our ruler with thunderous roar, we shall be there to see). The crowd became hysteric and Bano had to stop till the cheers subsided to resume her singing, as Faiz’s grandson Ali Madeeh Hashmi who was present in the concert narrated.

As her sonorous voice rang in the packed hall, Jab arz-e- Khuda ke kaabe se/Sab buut uthwae jaenge/Hum ahl-e-safa mardood- e-harm/Masnad pe bethaye jaenge/Sab taaj uchale jaenge/ Sab takht girae jaenge/ Hum dekhenge (When from the abode of God, all false idols will be removed, then we, the pure who have been exiled from his sacred place, will be seated on the throne, when their crowns will be flung in the air and their thrones will be smashed, we shall be there to watch), the crowd broke into rapturous shouts of Inquilab Zindabad that filled the air inside the hall and reverberated outside.

As Hashmi recounted, “For those of us sitting in the hall, it was quite surreal. The clapping and cheers were so thunderous that it felt at times that the roof would blow off.” And when she finished the song, Bas naam rahega Allah ka / Jo ghayab bhi hai hazir bhi/ Jo manzar bhi hai nazir bhi/Utthega an-al-haq ka nara / Jo mai bhi hoon tum bhi ho/Aur raaj karegi Khalq-e-Khuda/Jo mai bhi hoon aur tum bhi ho (Only the God’s name will survive, who cannot be seen but is present everywhere, who is both the seer and the seen. A cheer will rise ~ I am the God, who is me and who are you too, and that God’s reign will prevail), the crowd refused to let her leave and demanded an encore which she had to oblige.

As Hashmi noted, it was this encore that was recorded surreptitiously by a technician that survives even today. As anticipated under the most brutal military dictatorship that Pakistan had ever known, a severe crackdown followed. That very night, the authorities raided the homes of the organisers and of those who attended the concert. They confiscated and destroyed all the recordings they could find. Anticipating this, a copy of the song was already handed over to a friend who could smuggle it out to Dubai where it was widely circulated. Faiz died in 1984 and General Zia died in 1988 in mysterious circumstances.

Today even in Pakistan, nobody mourns Zia-ul-Haq, but Faiz’s poetry has made him immortal. Among his poems, Hum Dekhenge has become an icon of liberty and a beacon of hope against tyranny and dictatorship in the entire subcontinent and beyond. Dictators and tyrants do not last forever, poems do. Hum Dekhenge has now become a controversial issue in India, after it became the anthem of protest during the countrywide agitation against the CAA and NRC. On 17 December, it was sung by the students of IIT Kanpur during a peaceful march within the campus.

A faculty member, who is no expert in poetry and obviously has no idea about the use of metaphors in poems, made a formal complaint to the Director, saying that the poem was anti-India and had words that could offend the sentiments of the Hindus. Instead of dismissing the complaint with the contempt that it deserved, IIT Kanpur overreacted and formed a panel to decide whether the poem was offensive to Hindu sentiments. In particular, the objection was against the use of the word buut and the phrase Bas nam rahega Allah ka.

One has to stretch one’s imagination beyond the wild to conclude that these metaphors are offensive. IIT Kanpur ought to have stuck to its core domain of engineering instead of venturing into poetry. It has subsequently issued a denial which is as weak as it is unconvincing. Now the poem is stirring the students in various campuses across India, including Jawaharlal Nehru University. Protests and dissent are the quintessence of democracy, indeed its lifeblood as well as safety valve. Any attempt to muzzle the voice of dissent by coercive tactics is bound to stoke violence on a wider scale.

While violence in all forms is to be condemned unequivocally, in the current spate of protests across the country against the CAA and NRC, the government must also claim its responsibility. It was not necessary at this juncture to uncork a genie that has the potential of dividing the country along sectarian and communal lines that threaten to tear the fabric of society apart, especially when the slowdown in economic growth demands vigorous efforts to set things right. The Indian State, as an entity of governance, cannot be so fragile as to cower before a few slogans and poems raised and recited by children.

Any democracy, especially a diverse one like India’s, is a land of million mutinies occurring every day. A government with the kind of massive mandate that it enjoys has no reason to feel endangered. It must also remember that no government lasts forever and today’s rulers will be tomorrow’s opposition. If the protesting voices are coerced into silence by today’s rulers, the consequences will continue to haunt them when they will need to raise their voices of protest, besides weakening the vibrancy of democracy we so cherish. Faiz had a turbulent life and suffered physically and mentally from the tyranny of the State throughout his life.

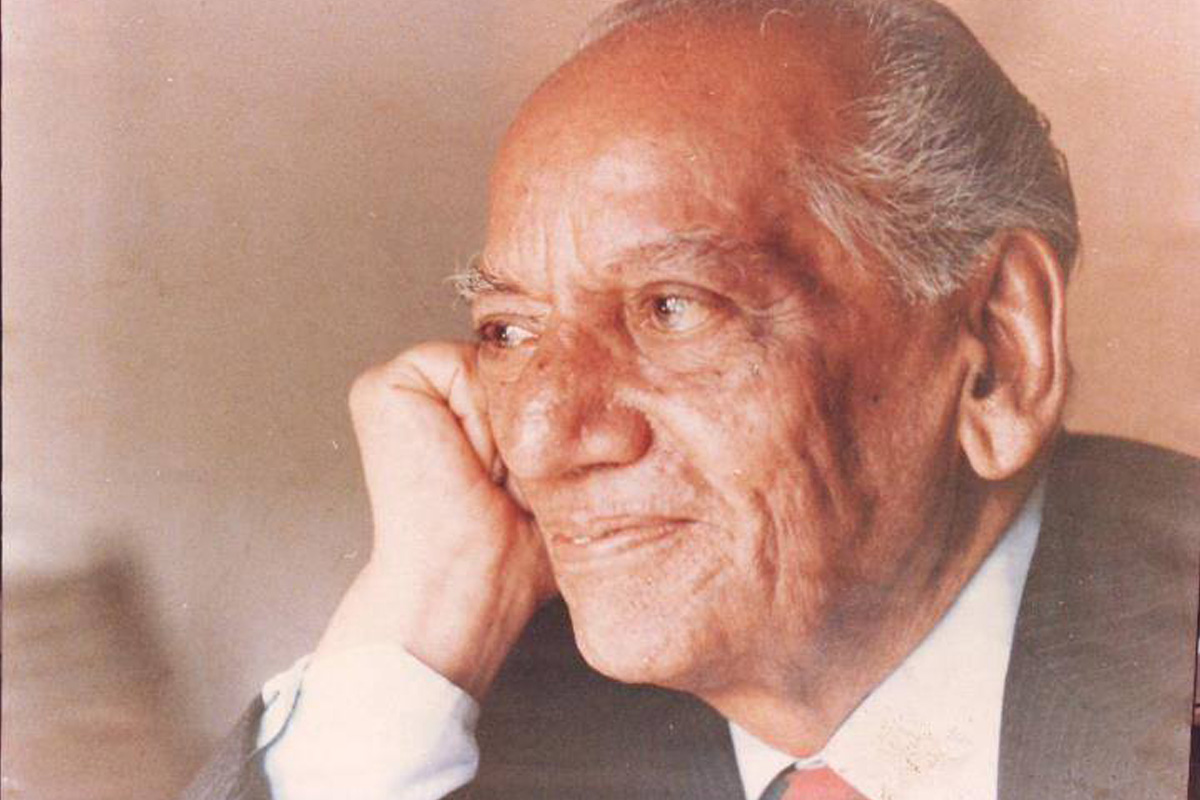

He was jailed in Pakistan in 1951 in the Rawalpindi Conspiracy Case as a co-conspirator against the State, went into exile in Lebanon when Zia-ul-Haq overthrew Bhutto in 1977, returned to Pakistan in 1982 and was promptly jailed again to be released after some time, and finally died in 1984 in Lahore. While he combatted atrocity and tyranny perpetrated by the military through his poetry, he never lost faith in love, which remains the fundamental inspiration of a poet anywhere at all times. He was awarded the Lenin Peace Prize in 1962. While receiving the prize in Moscow, he concluded his speech by quoting the Persian poet, Hafez Shiraj “Every foundation you see is faulty except love which is faultless.”

A government’s fundamental duty to society is to promote love. On 14 August 1947, Faiz wrote his famous Subh-i-Azadi (Dawn of Freedom) expressing his anguish at Partition. Yeh daag daag ujala, yeh shab-gazeeda sehr/ Woh intezar tha jis ka yeh who sehr to nahi (This stained light, this night-stung dawn is not the dawn we have so long been waiting for). It seems our wait for that dawn of freedom when the mind will be without fear and the world will not be “broken up into fragments by narrow domestic walls” is not yet over.

(The writer is a commentator. Opinions are personal)