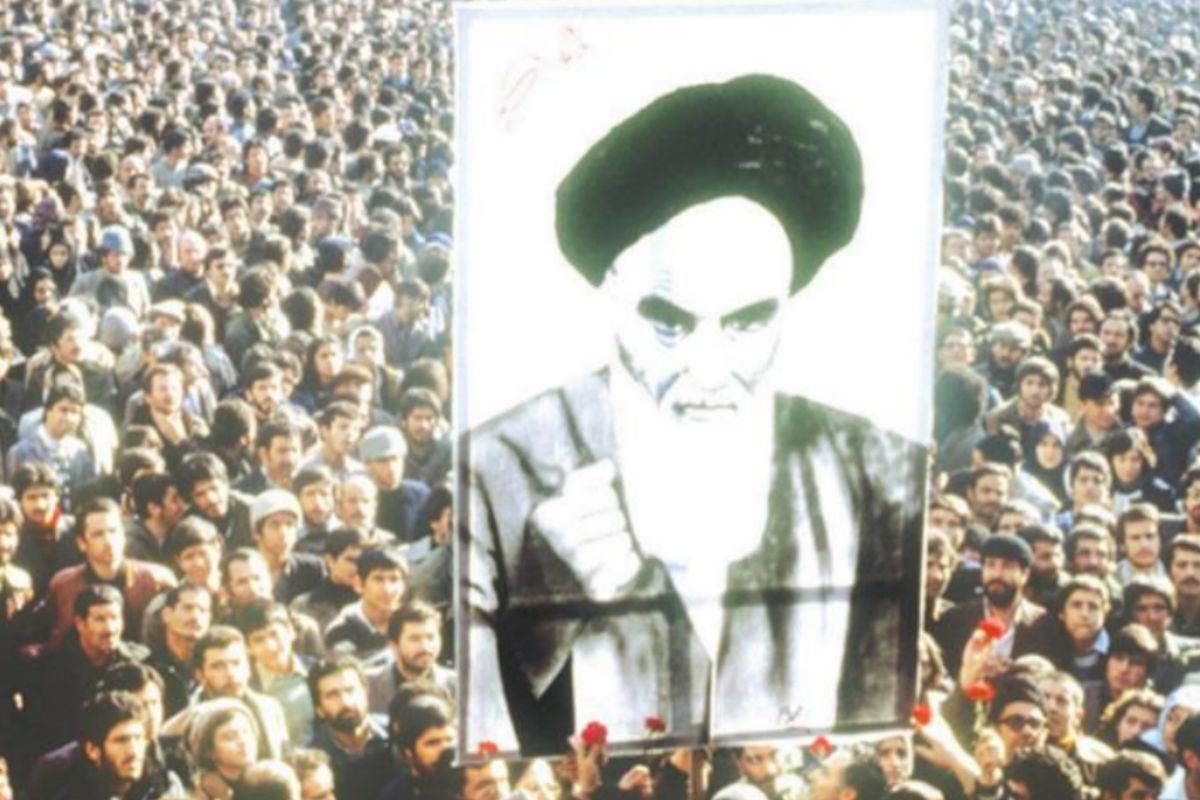

More than four decades ago, the unusually eloquent Polish foreign correspondent Ryszard Kapuscinski witnessed “a human river, broad and boiling, flowing endlessly, rolling through the main street [of Tehran] from dawn till dusk … a violent flood that in a moment will engulf and drown everything”.

It did, albeit not quite in the way many of the components of that flood had imagined. The obscenely repressive Pahlavi regime was overthrown in 1979, but the window of opportunity for a representative republican alternative was short-lived. Opposition to the Shah had by then been ingrained in virtually every segment of Iranian society and across the ideological spectrum, from the communist left to the Islamist hard right.

Advertisement

If the latter were predominant, it was partly because in previous decades the clergy, to some extent, had access to its pulpit, whereas liberal democrats and forces further to the left were ruthlessly crushed. Once in power, the theocrats echoed that strategy, silencing all dissent and introducing controversial prohibitions directed particularly against women.

A quarter-century earlier, Faiz Ahmed Faiz had dedicated a poignant poem to Iranian students, which begins (to loosely paraphrase it) by asking: Who are these altruists the rubies of whose beneficence drip into humanity’s begging bowl?

Iran’s trajectory in the latter half of the 20th century would have been remarkably different had not an Anglo-American intervention blocked the progress of the Mossadegh administration and reinstalled the Shah. The potential threat of a theocracy would at least have substantially been diminished. And Faiz would no doubt have been relieved if his verses did not loudly resonate 70 years later.

The protests that have proliferated across Iran since Mahsa Amini’s death in custody in mid-September are both uplifting and heartrending. The 22-year-old Kurdish visitor to Tehran was detained by the so-called morality police on September 13 and pronounced dead three days later. Almost no one buys the ridiculous narrative that she died of natural causes.

Not surprisingly, women have been at the forefront of the uprising that has seemingly engulfed Iran ever since, with the brutality of the state’s repressive apparatus adding to the pent-up wrath. The death toll so far is reported to be more than 100, which may well be an underestimate, amid hundreds more injuries and arrests.

Protests on a smaller scale in fact began a month before Mahsa Amini’s murder, when President Ebrahim Raisi decreed enhancements to the dress code for women, weeks after a national Hijab and Chastity Day was introduced in mid-July. Among those arrested for “improper clothing” was a 28-year-old writer and artist Sepideh Rashno, who was harassed on a bus, then arrested, and forced to apologise for her indiscretion on national TV after she had apparently been physically abused.

Women’s rights have invariably been a particular problem in Muslim societies in recent decades — albeit with vast variations. The ‘chaddar aur chardiwari’ aspects of the Zia regime came as a shock to Pakistanis precisely because that kind of nonsense had not previously been the norm. Ridiculous as they were, though, such “moral” restrictions thankfully never quite resulted in the restraints implemented in Iran or Saudi Arabia.

It’s also important to acknowledge, of course, that Muslim societies are far from the only culprits in discriminating against and stigmatising women. It is heartening that India’s supreme court has lately sought to extend abortion rights, for example, even as they are being curbed in the US, though more broadly the struggle for gender equity carries on. Much of Latin America and Africa, meanwhile, despite occasional instances of progress, are still struggling with the notion of equality between the sexes.

But significant segments of the Western world are hardly on the right track, with noticeable regressions from the US to Poland, and less obvious ones elsewhere. The kind of constraints imposed in Iran, though, may well be unique — even the Saudi regime has relaxed a few of its social strictures. Besides, the rage in Iran is also a response to various other factors, not least the economic woes that engulf all segments of society.

It may be unreasonably optimistic to view the current protests as the kind of tipping point witnessed in 1978-79. Yet one must fervently wish that the blood that drips into the receptacle of hope will not go waste. Iran will one day be liberated from the tyranny of the rulers. The deliverance may not be imminent, but it may well be in the train.

Fingers crossed. And however long it may take, the autumn of 2022 is likely to be commemorated as a turning point — the kind of moment when, as Faiz concludes, the seeds of hope blossomed once more in the perennial garden of rebellion.