Kailash Mansarover Yatra to resume soon: MEA

The government on Thursday suggested that the Kailash Mansarovar Yatra will resume soon.

Russell’s opposition to war did not stop with the end of World War I. He continued to remain a pacifist throughout. He strongly upheld the view that war was the outcome of ‘possessive impulses’. The best government is a world federation of Free states. In the years immediately preceding the Second World War, Russell was again an advocate of a policy of pacification

CHANDRAKALA PADIA | New Delhi | May 18, 2023 5:46 am

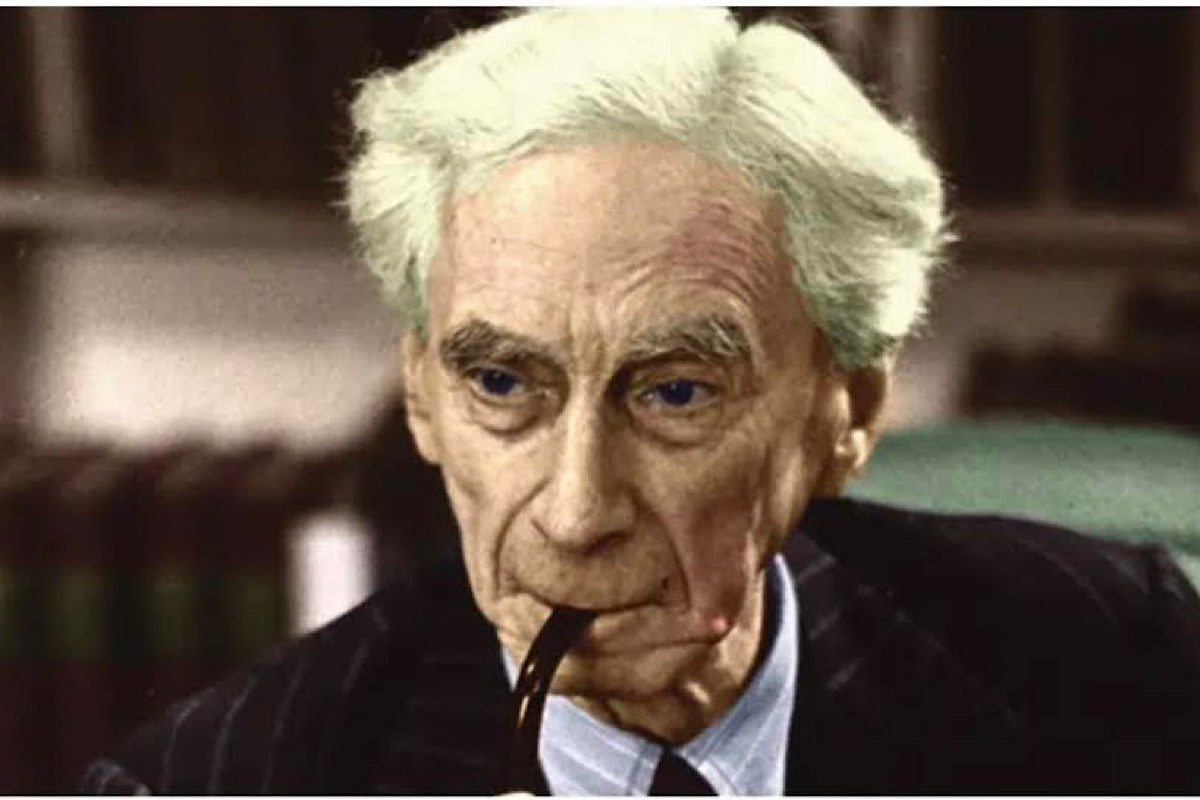

Bertrand Arthur William Russell (Photo:SNS)

Bertrand Arthur William Russell, 3rd Earl Russell, OM, FRS (18 May 1872 – 2 February 1970), is the most important philosopher of the 20th century, the most important logician since Aristotle, a mathematician, social critic, political activist, author of over 40 books and thousands of essays and letters addressing a myriad of topics, winner of the Nobel Prize in literature, and a pacifist.

The qualities that make Russell so different from other philosophers are his indomitable courage, unflinching spirit and capacity to stand by his views in even the most challenging circumstances for the poor masses, developing nations and marginalized peoples, even if it meant going against his own country or people.

Advertisement

One of the best examples of this are his speeches in favour of India’s independence against his own British Government as President of India’s League when he categorically mentioned, “The British government has been gravely at fault in the past, and Mr Churchill has been even more reactionary than the government, as appeared in his opposition to the Government of India Act”.

Advertisement

He acclaimed Gandhi’s contribution by regarding him “unquestionably a great man, both in personal force and in political effect. He molded the character of the struggle for freedom in India…. He had… that scrupulous honesty which later distinguished him…. Gandhi possessed every form of courage in the highest possible degree….” Besides this, his opposition to World War I and his country’s involvement in it to the extent of distributing pamphlets against his government, initiating his own people to work for ‘No Conscription Fellowship’, the courage to accept what he wrote against the British Government resulting in his imprisonment in Brixton Prison in 1918 for 6 months, bear testimony to this. Not only this, as a result of his antiwar campaigning, Russell was dismissed from his lectureship at Trinity College.

Although Trinity offered to rehire him after the War, he turned down the offer, preferring rather to pursue a career as a journalist and freelance writer rather than to succumb to any authority. Russell’s opposition to war did not stop with the end of World War I.

He continued to remain a pacifist throughout. He strongly upheld the view that war was the outcome of ‘possessive impulses’. The best government is a world federation of Free states. In the years immediately preceding the Second World War, Russell was again an advocate of a policy of pacification.

He aimed at a dialogue with the Nazis to prevent a new conflict, but in 1940 he recognized the impossibility of dealing with Hitler.

Hence he had to change his views. He believed that though war was an evil, but in extreme circumstances, war itself could be the lesser evil. He called his position, “relative pacifism”.

But this position did not deter him from opposing unjust wars fought by powerful nations against poor nations. This is the reason Russell became one of the staunchest critics of America’s involvement in the Vietnam War.

He spent the 1950s and 1960s opposing the Vietnam War and primarily in campaigning against nuclear armament. The 1955 Russell-Einstein Manifesto was a document calling for nuclear disarmament and was signed by 11 of the most prominent nuclear physicists and intellectuals of the time.

Jawaharlal Nehru was one of them. In 1961, Russell was tried and sentenced to prison for two months at a demonstration in London against the proliferation of nuclear weapons.

Considering his advanced age (he was 89), the judge offered to release him if he promised “good behavior” ~ but even at that age Russell did not yield, and refused.

He also relinquished his privilege, as a Peer of England, of being exempted from arrest without authorization from the House of Lords. In 1966-1967, Russell worked with Jean-Paul Sartre and many other intellectual figures to form the “Russell Vietnam War Crimes Tribunal” to investigate the conduct of the United States in Vietnam.

He wrote a great many letters to world leaders during this period. He ceaselessly worked for the release of political prisoners in over forty countries where they were held, half forgotten, for deeds which were often praiseworthy.

He sent many representatives to both Israel and Egypt to discuss the separate and joint problems of those countries. In turn, they sent their emissaries to meet him.

He was very much concerned with the plight of the Jews in the Soviet Union and carried on a considerable and continued correspondence with the Soviet Government. In addition, he made several appeals on behalf of a very large number of Jewish families in Eastern Europe separated during World War II and wished to rejoin their relations abroad, usually in Israel.

Due mainly to his efforts, many prisoners in many lands were freed. Russell was very upset when East Germany abducted and imprisoned Heinz Brandt, who had survived Hitler’s concentration camp.

Russell found it so inhuman that he returned to the East German Government the prestigious Carl Von Ossietzky Medal which it had awarded him.

As a result, Brandt was soon released. It was due to his pioneering work for prisoners that the American Emergency Civil Liberties Committee bestowed upon him the Tom Paine Award in January 1963.

Throughout his life, Russell worked in this direction and sent fact-finding representatives to many parts of the world. They travelled to most European countries, and to many Eastern countries ~ Cambodia, China, Ceylon, India, Indonesia, Japan and Vietnam.

They were also sent to Africa ~ Ethiopia and Egypt and the newer countries of both East and West Africa. They travelled to the countries of the Western Hemisphere too.

Due to Russell’s illustrious personality and sincere efforts, these representatives were generously welcomed by the heads of whichever country they went to.

Russell himself carried on prolonged correspondence with the various Heads of State and officials, and had discussed in London a variety of international problems with them, particularly with those from Eastern Europe, Asia and Africa.

As all this work steadily increased and became increasingly demanding, Russell realized that it was not possible to work alone.

Hence, with the help of Ralph Schoenman and Christopher Farley, he established the Bertrand Russell peace foundation.

This foundation was to deal with the more immediately political and controversial side of the world.

Though it was very difficult to generate funds, the foundation could sustain itself on the generous grants made by numerous artists, painters, sculptors and musicians of different countries.

(The writer is former Professor and Head of Department of Political Science, Benares Hindu University)

Advertisement

The government on Thursday suggested that the Kailash Mansarovar Yatra will resume soon.

Assam Chief Minister Himanta Biswa Sarma on Thursday called upon the Indian leadership to accept what he termed the "enduring civilizational divide" between India and Pakistan, urging the country to abandon long-held notions of reconciliation with its neighbour.

India on Thursday said it is working closely with Belgium for the extradition of fugitive diamantaire Mehul Choksi, who was recently arrested in the European country.

Advertisement