As tempers flared in Washington…

Donald Trump and his Vice President JD Vance together targeting Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskky in full media glare is a spectacle not witnessed in years.

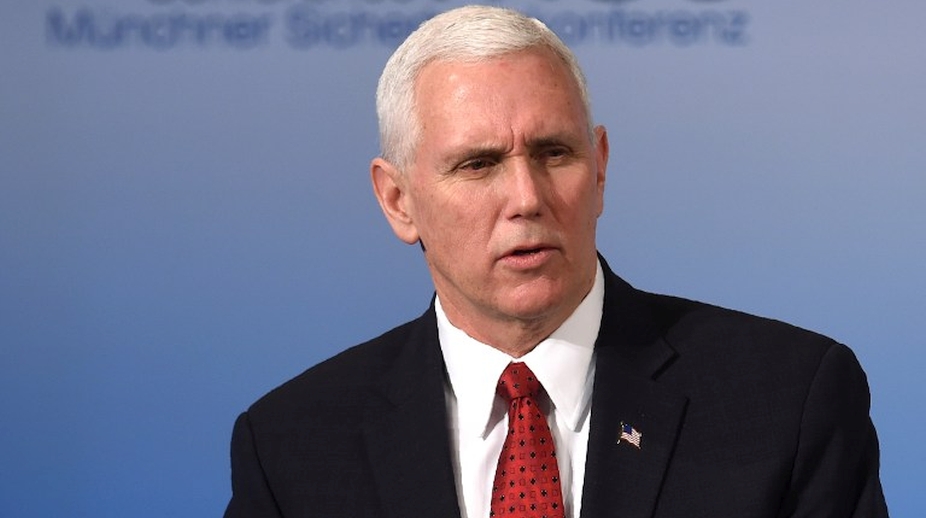

PHOTO: AFP

During the presidency of George HW Bush, his Secret Service detail was reputedly under orders that if anything happened to him, they should immediately shoot his vice president Dan Quayle — to prevent him becoming president. In the present US administration, the orders are: if anything happens to Vice President Mike Pence, first shoot President Donald Trump.

The selection of a US vice president is always a tricky business. Every president hopes to find a person who can complement, not supplant him. Invariably, the choice falls on someone with more experience than ambition, on a man who can be trusted to remain a patient Prince of Wales than a restless heir apparent in waiting.

Advertisement

Some US presidents suffered the same disease that the Guelph Georges did: they hated their potential successors. President Dwight Eisenhower disliked his vice president Richard Nixon, refusing on one occasion to defend him during a corruption investigation. Then Nixon endured being spat upon by angry Venezuelans during a tour to their country in 1958. John F. Kennedy saw his VP Lyndon B. Johnson as a useful Mr Fix-it Southerner rather than his anointed torch-bearer. Nixon, when finally president, in the few hours that he did sleep never dreamed that his VP Gerald Ford would succeed him.

Advertisement

Dan Quayle reached the highest level of his incompetence when he became Bush senior’s VP. The White House must have quaked when Quayle pronounced: “I have made good judgements in the past. I have made good judgements in the future,” or misspelt before an elementary class the vegetable as ‘potatoe’.

Today, Trump’s White House must be watching with apprehension whenever his Vice President Mike Pence opens his mouth. Pence, like Quayle, is from Indiana, but there the similarity ends. Anyone, though, who saw VP Mike Pence at his press conference with Nato Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg in Brussels this week realised that while Trump may well be a Svengali, Pence was certainly not his Trilby.

Pence articulated US foreign policy regarding shared financing of Nato with consummate diplomacy and precision. Within a few sentences, he restored the confidence of the Europeans in US’s leadership of the English-speaking world. And with a snake-oil salesman’s sleight of tongue, he explained away the inconsistencies between his president’s indefensible pronouncements and US’s more enduring global commitments and interests. At a stroke, he demonstrated why a good vice president can be more precious than a bad president. VP Mike Pence is not a mouthpiece VP: in time he may well reveal himself as the Svengali behind Svengali.

The US experience with VPs may explain why Pakistani leaders are loath to nominate deputies. Where others look for running mates, they prefer accomplices. Ayub Khan as a former chief of army staff-turned-elected president did not choose Yahya Khan as his successor. He chose the Pakistan Army whose head happened to be Gen Yahya Khan. Zulfikar Ali Bhutto saw his own successor in Benazir and, after her, Bhutto-ism. Ziaul Haq anointed Ghulam Ishaq Khan, the man who had midwifed him into power. Asif Zardari and Mian Nawaz Sharif share a disease known as congenital myopia: they cannot see a successor outside their family circle.

Mr Sharif must envy Zardari’s Houdini-like skills in being able to escape with such oily dexterity from every trap. Ironically, while Zardari and Gen Musharraf enjoy their retirement abroad, Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif is finding his retirement home in Park Lane in jeopardy. Like some modern Laocoön, he finds himself and his two sons entangled in the suffocating coils of the serpentine judicial system.

Neither he nor his protagonist Imran Khan had expected the delivery of a judicial verdict on Panamagate to be such prolonged labour. The public is tired, the press is tired, court functionaries are tired, my lordships must be tired. Only the legal counsel are not. They remain indefatigable in their pursuit of the elusive white stag of truth.

Now that civil courts have been supplemented by military courts, is it time to practise reverse osmosis, to let military jargon seep into judicial parlance? If so, shouldn’t the concept of surgical verdicts become a feature of the judicial process?

The new Chief of Army Staff Gen Qamar Bajwa, in making punitive strikes against terrorist bases in Afghanistan and within Pakistan, has demonstrated that while he may be Nawaz Sharif’s choice, he is his own COAS, and that even Punjab’s administration can no longer enjoy a fraternal exemption.

When Gen Bajwa took over, he said that terrorism, not India, was the prime enemy. Today, he uses his double-barrelled guns to fire in two directions — westwards against Afghanistan and simultaneously eastwards against its behind-the-curtain Svengali.

Meanwhile, the Pakistani public, to its cost, has learned a new adage: power corrupts, and corruption in power all too often leads to immunity.

Dawn/ANN

Advertisement