In the immediate aftermath of Indira Gandhi’s assassination in 1984, more than 2,700 people were killed in the anti-Sikh riots ~ more than 2,000 in Delhi alone ~ and the government of the day did little or nothing to protect them. The violence of the Khalistan movement, Mrs Gandhi’s initial support to the politics of the religious conservative, Jarnail Bhindranwale, in an effort to undermine the Akali Dal, the largest Sikh political party, the counterinsurgency leading to Operation Blue Star, religious sectarianism, the killing of the Prime Minister and the gory aftermath are fairly well-documented. For three days in November 1984, certain parts of Delhi resembled Mano Majras ~ a small Indian frontier village in Khushwant Singh’s novel Train to Pakistan ~ with all the killings, arson and rape.

Besides this carnage, there is another shoddy reality. Rajiv Gandhi capitulated to the Muslim fundamentalists in overturning a 1985 Supreme Court ruling that gave Shah Bano and all Muslims the right to seek alimony. To appease the Hindu majority, his government supported the Ram Janambhoomi movement. The Sikh riots, the Muslim Women’s Bill, and the support extended to the Ram Janambhoomi movement affected the standing of the Congress. The party irretrievably lost its secular character, which was a cardinal principle of the Nehruvian Consensus.

Advertisement

If it was tactless on the part of Rajiv Gandhi not to have considered the carnage worthy of an inquiry ~ calling it a “dead issue” ~ what was even worse was the derailment of investigation into the 1984 massacre by a ‘clutch’ of commissions and committees of inquiry set up to ascertain facts. Rajiv only yielded to the demand for an inquiry as the Akali Dal leader, Sant Longowal, had insisted on it as a pre-condition for talks on the raging Punjab crisis.

The inquiry commission appointed in November 1984 and headed by Ved Marwah, then additional commissioner of police, Delhi, to inquire into the role of the police during the antiSikh carnage reached a dead end by mid-1985 at the instance of the Akali leader Sant Harchand Singh Longowal. He had listed a set of preconditions when Rajiv, desperate for a breakthrough in Punjab in 1985, persuaded him to sign a peace accord with him. One such precondition was the setting up of a judicial commission to inquire into the massacre. This led to the Misra Commission in May 1985.

A succession of governments have set up a bevy of commissions and committees ~ Marwah Commission, Mishra Commission, Kapur Mittal Committee, Jain-Banerjee Committee, Potti Rosha Committee, Jain Aggarwal Committee, Ahuja Committee, Dhillon Committee, Narula Committee and the Nanavati Commission. It is hard not to wonder how dark hints at the enormity of the crime could lead not to justice but to further obfuscation.

Does one remember poor Jarnail Singh, who shot to fame for having flung his Reebok runner at P Chidambaram when he was the Union Home Minister. He has mentioned the CBI’s clean chit to the Congress leader Jagdish Tytler, accused as a prime instigator.

By awarding a life sentence to Sajjan Kumar, the High Court is said to have brought ‘closure’ to some families who saw their loved ones being incinerated alive, but has it? Sajjan was convicted 34 years after his crime. In the acquittal of all the 22 accused in the 2005 Sohrabuddin Sheikh encounter case, there was a miscarriage of justice through a process of cover-up, destruction of evidence, poor investigation, influencing of witnesses, open use of money, threat and intimidation, violation of rules and procedures and many other wrongful means.

Within two days of the submission of the inquiry report into the riots by Justice GT Nanavati on 10 February 2005, the furore over the Commission’s report and the Home Ministry’s Action Taken Report (ATR) forced the government to concede an adjournment motion debate in the Lok Sabha. Prime Minister Manmohan Singh, while admitting in Parliament that the anti-Sikh riots of 1984 were a shameful episode in the country’s history, apologised “not only to the Sikh community but the whole Indian nation” with the assertion that “what took place in 1984 was the negation of the concept of nationhood. enshrined in our Constitution”.

The contrition was followed by the resignation of then Minister for Overseas Indian Affairs Jagdish Tytler, against whom the Commission had found “credible evidence” of a possible role “in organising the attacks”. Another senior leader from Delhi, Lok Sabha member, Sajjan Kumar, resigned as Chairperson of the Delhi Rural Development Board, a position of Cabinet rank in the Delhi government.

The Prime Minister made a “solemn promise” in Parliament that “wherever the Commission has named any specific individual as needing further examination or specific case needing reopening and reexamination, the government will take all possible steps within the ambit of the law”.

Was the promise kept? Shiromani Akali Dal (SAD) president Sukhbir Singh Badal recently asked Congress president Rahul Gandhi to expel the 1984 anti-Sikh riots accused Jagdish Tytler from the party as well as the newly appointed Madhya Pradesh Chief Minister Kamal Nath, the nine-time MP from Chhindwara. Though known to be an efficient administrator, he was indicted by the Nanavati Commission for his role in the 1984 anti-Sikh riots.

However, the charges against him were dropped due to lack of evidence. As perceptions matter a lot, Rahul Gandhi could have spared Kamal Nath to do justice to the wounded Sikh sensibilities. No matter what the courts said, well-known Congress leaders of Delhi such as Tytler, HKL Bhagat, Sajjan Kumar, Dharam Das Shastri and Arjun Das were never above board in popular perception. Can the BJP afford to feel smug or claim the moral high ground vis-a-vis the Congress.

The two major political parties stand severely accused. Therefore the BJP cannot revel in the fact that the 1984 Sikh massacre seems to be recalled more often than the Gujarat riots of 2002.

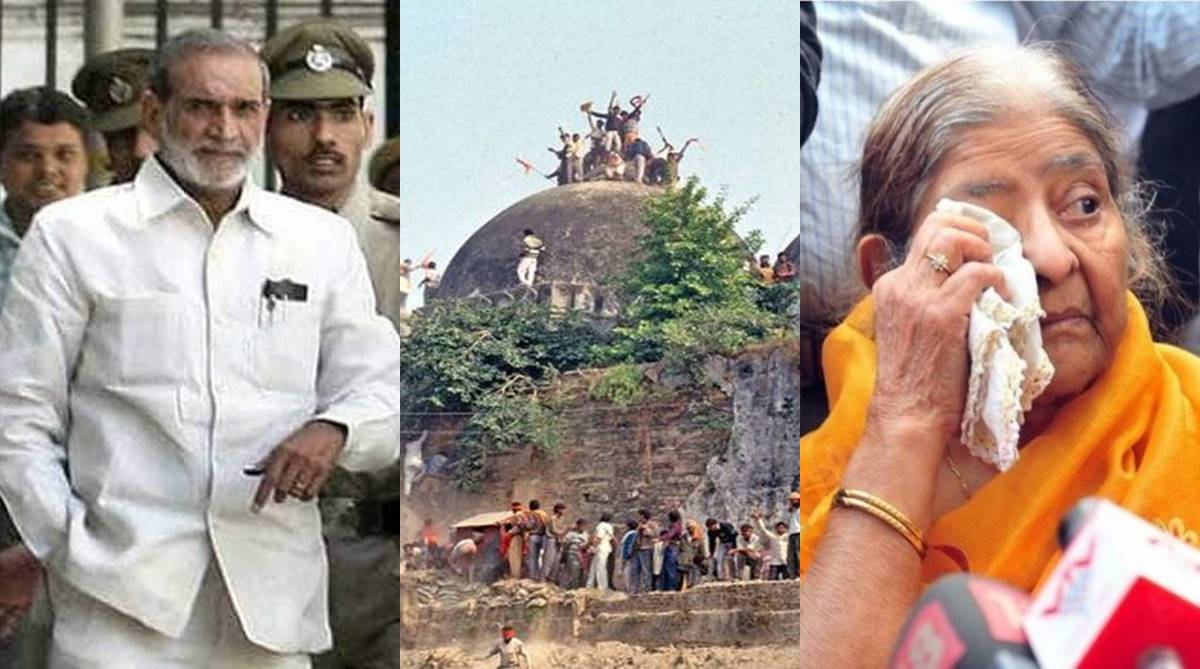

While senior Congress leaders encouraged wholesale mob violence against Sikhs in Delhi in 1984, the BJP leaders played a similar role in attacks against Muslims in Gujarat in 2002. Following the demolition of the Babari Masjid in 1992, some 2000 people were killed in communal riots in Ayodhya, Mumbai and beyond. Hindu hardliner parties, including the VHP and the BJP used the Ayodhya issue as a rallying call to Hindus throughout India.

The complicity of the Gujarat government in supporting the riots ~ the most horrendous massacre of innocent citizens belonging to the minority community in post-Independence India ~ is a blot that is impossible to be removed. Prime Minister Atal Behari Vajpayee remarked that had Muslims condemned the Godhra incident, such a massacre in Gujarat would not have taken place. Though Vajpayee had reminded Modi of his Rajdharma (though without taking any action against him), he often indulged in flip – There is no scope for moral righteousness.

The three major instances of barbarism in India over the past 34 years ~ the anti-Sikh riots of 1984, the Babari riots of 1992 and 1993, and the Gujarat riots of 2002 ~ will continue to be regarded as monstrosities. The culprits either roam free or an effete leader, past his prime, is convicted as an act of cruel tokenism. Overall, punishment for a crime has been reduced to an exercise of too little and too late.

The political careers of Jagdish Tytler and Sajjan Kumar were almost over when their involvement in the 1984 riots came into question. Mark Levene once defined “savagery” as ‘the state-organised total or partial extermination of perceived or actual communal groups’. It is a travesty of justice to see the perpetrators unpunished and roaming around scot free.

(The writer is a Kolkata-based commentator on politics, development and cultural issues)