The annual get-together of European military and security chiefs in the southern German city of Munich is a traditional venue for governments to reassert their commitments; the conference served as inspiration for the Shangri-La Dialogue in Singapore, which now performs the same function in Asia.

But this year’s Munich gathering, which concluded over the weekend, was particularly noteworthy, for it offered a first glimpse into the defence policies of Donald Trump, the only United States president since World War II to have dismissed America’s military alliance with Europe as “obsolete” and the only US head of state who appears to believe that the potential break-up of the European Union may actually serve America’s interests.

Advertisement

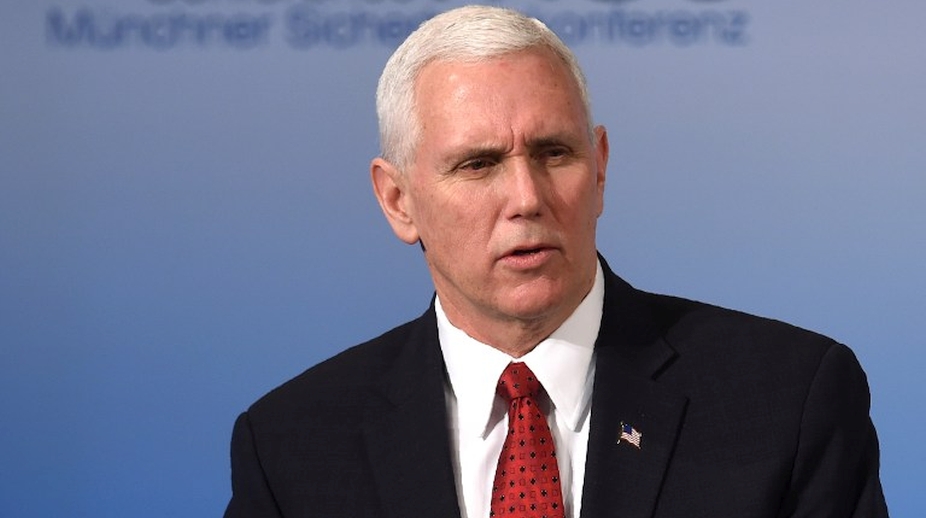

After weeks of transatlantic spats, the Munich Security Conference braced itself for the worst. But it ended on the best of tones, as US Vice-President Mike Pence reiterated Washington’s commitment to “stand with Europe today, and every day”, and as Europeans restated their attachment to the transatlantic link. “Europe needs North America, and North America needs Europe,” Mr Jens Stoltenberg, secretary-general of the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (Nato), the US-led military alliance in Europe, responded.

But despite this renewal of their marriage vows, the reality remains that US-Europe relations are still facing their biggest challenge in seven decades, and the discussion about what needs to be done to fix them has barely begun.

Nobody doubts the significance of the transatlantic link. Notwithstanding the economic rise of Asia, the US-EU economic relationship remains the world’s largest, accounting for around one-third of global trade in goods and services, and just under half of the global economic output.

Its 28 member states spend a staggering US$1 trillion on their armed forces each year, have a combined force of 3.1 million servicemen and women, and include the nuclear arsenals of no fewer than three of the world’s nuclear powers. A bigger punch in both economic and military terms cannot be imagined.

But there is equally no doubt that the military relationship between the US and Europe is ailing. Since Nato was founded in 1949, the Europeans never paid their full share of the expenses. By the early 1990s when the Cold War ended, the US alone paid for half of Nato’s military capabilities. Since then, matters have got worse.

The Americans are now responsible for around 70 per cent of Nato assets, despite the fact that in both terms of population and combined size of their economies, the Europeans’ are bigger than the US’.

Efforts to shame the Europeans into spending more are hardly new.

In prophetic words which date back to 2011, then US Defence Secretary Robert Gates publicly warned that Nato faces a “dismal future” of “collective military irrelevance” unless its European members increase their financial contributions. But the pledge which European governments then made to devote at least 2 per cent of their gross domestic product to defence each year remains unfulfilled: apart from the US itself, only Britain, Greece, Poland and Estonia have redeemed the pledge. Europeans cannot, therefore, plausibly claim to be surprised that the Trump administration now expects quick progress, or that the new US officials are even less diplomatic on this point.

“No longer can the American taxpayer carry a disproportionate share of the defence of Western values; Americans cannot care more for your children’s future security than you do,” said US Defence Secretary James Mattis. Some European officials still resent being lectured to. With his curious knack of saying the wrong thing at the wrong time, Mr Jean-Claude Juncker, president of the European Commission, the EU’s executive body, rejected American “pressure”, claiming that the EU’s broader contributions to global development should also be taken into account. But that was very much a minority view; most European decision makers accept that they should dig deeper into their own pockets.

Still, the Trump administration’s insistence on increased European contributions is misconceived, and can lead only to a sterile debate which will do little to improve transatlantic links. To start with, the Europeans are already doing more. Countries such as Poland and Romania, much closer to Russia which they consider as a threat, are increasing their defence budgets at the fastest rates in Europe. Germany and France have also pledged additional funds.

True, they should have done much more, and much earlier. But the Europeans have already accepted that the burden of proof of their commitment now lies with them. However, looking at bare numbers does not tell much about the actual European defences.

For even if the political will to boost military expenditures was there, the capacity to absorb so much extra cash into the defence sector is absent. Germany alone, for instance, would have to divert about €30 billion of extra expenditure into its defence budget each year, a huge amount which clearly would take years to ramp up. Furthermore, it is not so much the volume of spending but, rather, how one spends cash which matters more. Nato member states are supposed to devote 20 per cent of their military budgets each year to the purchase of new hardware but, on average, they spend only 11 per cent on new weapons. Greece, for instance, meets the 2 per cent of GDP spending target but blows most of the cash on pension liabilities for its servicemen.

So, what Europe and the US need is not an accountants’ dialogue but a broader discussion about how their military relationship is going to function, and what the Americans are still prepared to do.

President Trump inherited an ambitious programme of military involvement with the Europeans, which included a plan to place four Nato multinational battalions – including one commanded by the US – nearer the borders of Russia, in order to bolster the defences of fragile countries.

The current White House also inherited a so-called “European Reassurance Initiative”, a plan to enhance the capabilities of former communist countries which are now members of Nato. At least for the moment, however, there is no signal from Washington whether the Trump administration intends to proceed with these plans, and that matters more to cementing transatlantic relations than all the discussions about defence expenditure targets.

And overshadowing everything is the thorny issue of Russia. In Munich, Vice-President Pence sought to reassure the Europeans that the US would “continue to hold Russia accountable” for the illegal annexation of Crimea, and for fomenting the war in Ukraine.

But at the same time, Pence also told the Europeans that Washington will continue to “search for new common ground” with Russia “which, as you know, President Trump believes can be found”.

Europe is not against a dialogue with Moscow; after all, the Europeans have frequently argued that the US should pay more attention to engaging with Russia.

But they fear that Trump’s idea of a deal is one negotiated above the heads of Europe, directly with Moscow. And they also resent what appears to be the US President’s premise that Russia is a potential ally in a joint effort to contain the threat Trump considers most acute: that of China. Such plans to enlist Russian support against China are not only being dismissed in Europe as wrong-headed, but they are also seen as deadly to the future existence of the Nato alliance.

Ultimately, all the participants in the Munich dialogue laboured under a polite, diplomatic delusion that it is possible to isolate military and security questions from the deeper worries which Europe has with President Trump’s dismissal of the advantages of free trade and globalisation, and that it is feasible for Washington and its European allies to pretend that their security relationship remains unchanged, while they disagree on almost everything else the US President plans to do.

It fell only to Angela Merkel, the German Chancellor whose country hosted the event, to warn that it remains to be seen whether Europe and the US “will be able to act in concert or fall back into parochial politics”. It was a clear admission that the world’s most important security link, although durable, may still need rescuing.

The Straits Times/ANN