The fiftieth anniversary of the independence of Bangladesh is being celebrated all over. Numerous books and articles have been published by scholars and practitioners from India, Bangladesh and even Pakistan. On the Indian side, books by former ambassador Chandrashekhar Dasgupta India and the Bangladesh Liberation War (Juggernaut, 2021) and retired colonel G S Batabyal Politico-Military Strategy of the Bangladesh Liberation War, 1971(Routledge, 2020), among others, analyse the history and experience of India’s political, diplomatic and military actions.

Noted authorities from Bangladesh like Junaid K. Ahmad and Ishrat Husain, in their articles, focused on the course of socioeconomic regeneration in Bangladesh, especially during the last few decades, that is now being globally acknowledged. From Pakistan, one reads accounts of how the discredited defence personnel were treated and how the country is yet to come to terms with the debacle.

Advertisement

In this context, a book Recollections of a Civil Servant-Turned Banker (Pathak Shamabesh Bangladesh, Dhaka, 2019) by Md. Matiul Islam, a distinguished bureaucrat who spent seventeen years in the Civil Service of Pakistan, two years in the private sector there, six years in the Government of Bangladesh (being its first Finance Secretary) and sixteen years thereafter in the World Bank and the UNIDO, deserves special mention. I met this gentleman in 1990 when he was serving as the Country Director of UNIDO in Delhi and I joined the UNDP office, on secondment from the IAS.

Islam’s book is a collection of essays, some published and a few unpublished, divided into eight parts, that broadly covers his personal life and career trajectory. Though not written in the style of a memoir, the parts somehow fall into place and create a narrative that is rich in detail and compelling to read. It traces the turns in his evolution as a multi-dimensional person who, despite achieving a great deal as an administrator, retained goodness of heart and simplicity of spirit.

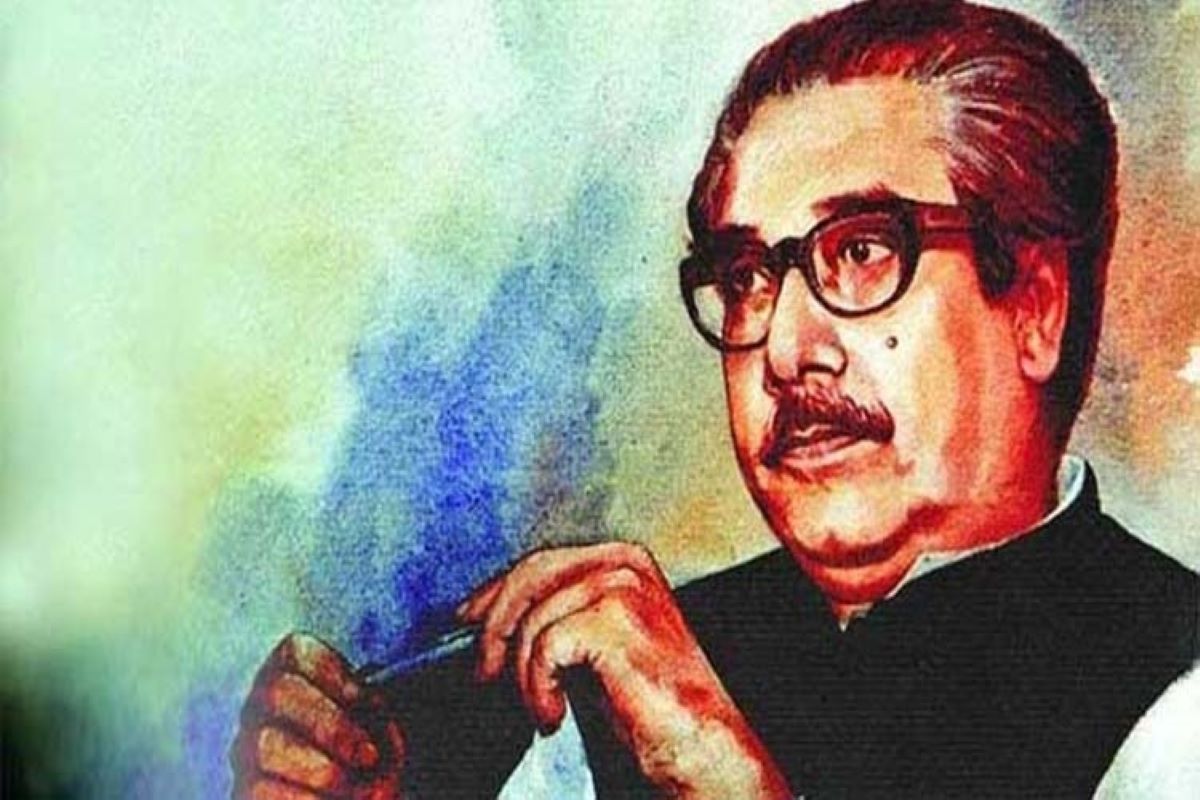

More than that, the book throws important insights into the working of the higher bureaucracy in Pakistan and Bangladesh, the enormity of problems that as a trusted lieutenant of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman he had to face while steering the nation through, and his grateful remembrance of people, including fromIndia, who had left a deep impress on his mind. Also, about the role of providence in human life.

Islam met Sheikh Mujib for the first time in 1957, when he was in Harvard pursuing a masters’ degree in public administration and Mujib, having resigned as a minister in order to devote time for party work, went to the US under a leadership programme and was admitted to Boston General Hospital for surgery.

This marked the beginning of an association that continued till the latter’s brutal assassination in 1975. Islam describes lovingly, but with the impartiality of a seasoned bureaucrat, the sterling qualities of the Bangabandhu whom he first saw in Calcutta in 1946. Islam went to Calcutta to begin his college education when Mujib was a final year student in Islamia College.

Briefly, Islam also narrates what he witnessed on Direct Action Day, 16 August 1946. With life turning uncertain, he left Calcutta after the announcement of partition. Being selected to the Civil Service of Pakistan in 1952 (qualifying simultaneously as a chartered accountant), he had his run of usual postings, having worked as a District Magistrate of Chittagong and for a long spell in the Department of Finance in East Pakistan.

In 1957, Sheikh Mujib, as a young minister, had set up the Film Development Corporation on behalf of which Islam later came to Calcutta to import twelve Bengali films. He met Satyajit Ray, and the maximum price was paid for Apur Sansar ~ Rs 25,000! After the problem started in 1969 with Yahya Khan imposing Martial Law and ousting President Ayub Khan, Islam faced the worst humiliation for a civil servant, on trumped up charges, that virtually ended his career in the Pakistan government.

The forced retirement when he was still in his thirties made him work for the private sector for two years. Interestingly, a day after Bangabandhu was swornin, Islam was appointed as the Finance Secretary of the new Government. This is how destiny unfolds! But life was not easy.

As he reminisces, “The Governement coffer was empty, the foreign exchange reserve was zero (except for US $5 million deposited by the Government of India with the RBI, in the name of Bangladesh Government) and all foreign exchange earnings arising out of exports from the then East Pakistan until 16 December 1971 were pre-empted by the Government of Pakistan… The cost of running the Government had tobe met without the benefit of a budget, new departments and ministries created, foreign missions opened…”

The list is endless, including the need to demonetise Pakistani currency notes in circulation! In layman’s language, Islam chronicles the process of bringing the economy back to the rails, under the guidance of enlightened and pragmatic leaders like Sheikh Mujib and Finance Minister Tajuddin Ahmed. Islam’s story of those heady and difficult days, including ‘An Eyewitness Account of Indira-Mujib Talks on Bilateral Issues, February, 1972’, provides a nuanced perspective of these historical events, interspersed with humorous incidents.

Heroes of the war for freedom are rightly remembered, but rarely are those who worked behind the scenes in developing a free nation. While Islam’s respect for Sheikh Mujib is understandable, his account of the post-Mujib era under Ziaur Rahman, especially in development of the private sector, also deserves notice. Ziaurwas assassinated by his own army colleagues in Chittagong.

When rumours were rife that General Ershad was planning a coup and that Islam was likely to be made Finance Minister, he left for Vienna to join the UNIDO. The book contains interesting snippets from Islam’s stint as Alternate Executive Director of the World Bank during 1973-77, including encounters with its President, Robert McNamara.

Islam’s long tenure at the Finance and Industry departments and his qualification as a chartered accountant equipped him to play an important role as a banker in his later life. The tender side of Islam’s personality gets reflected in his fond remembrances of people who mattered the most in his life. Other than his close family members including his mother [My Gateway To Heaven], he recalls, among others, Dr S R Sen, thenoted economist.

About his mother, “She was like an island of peace and an oasis of hope and love. At the age of 16, I left home for Calcutta for higher studies but never missed the opportunity to come to Barisal to be with her. The hardship of the journey, the sleepless night in the steamer from Khulna to Barisal, was all forgotten the moment I reached home to my mother…” Islam shows an amazing ability in dealing with complex issues like ‘Realities of Division of Assets between Pakistan and Bangladesh’ as with emotional ones like his last meeting with Sheikh Mujib.

The seamless manner in which the official matters and the personal issues are discussed, as also the warmth and empathy the book exudes combine to make it a delectable read. There are beautiful, some historically significant, photographs too. At around ninety and still active in Dhaka as the Chairman of a prominent financial institution, Islam is among the last surviving members of the old guard who had been instrumental in the momentous transformation of their motherland.

On the killings of Ahmadias in 1952 at Lahore, Sheikh Mujib observed: “I know at least this much that no one shall be murdered because he holds views different from mine. That certainly was not what Islam taught and such an action was tantamount to a crime in the religion.”

While returning from their first visit to the USSR, “I was summoned by the Prime Minister in the VIP cabin. The Prime Minister made a very unusual request. He asked me to sing a Tagore song for him. With the noise made by the four engines as the background music, I did my best to carry out the command of a great man…”

During a visit to Dhaka, while serving with the World Bank, Islam called on Sheikh Mujib on 7 August 1975, to take leave of him. What the Prime Minister said in parting shocked him, “Come to my Janaza”. He was assassinated eight days later. Did he have a premonition?

(The writer is a retired IAS officer)