When Shyam Benegal credited Satyajit Ray for revolutionizing Indian cinema

Shyam Benegal praised Satyajit Ray as the genius who redefined Indian cinema, leaving an unmatched legacy that transformed filmmaking.

One should ask whether all these exhibitions, retrospectives, lectures and seminars, books and articles have succeeded in making Ray’s treasure reach the unreached, and whether his luminous creativity is being subjected to questioning in the context of present times.

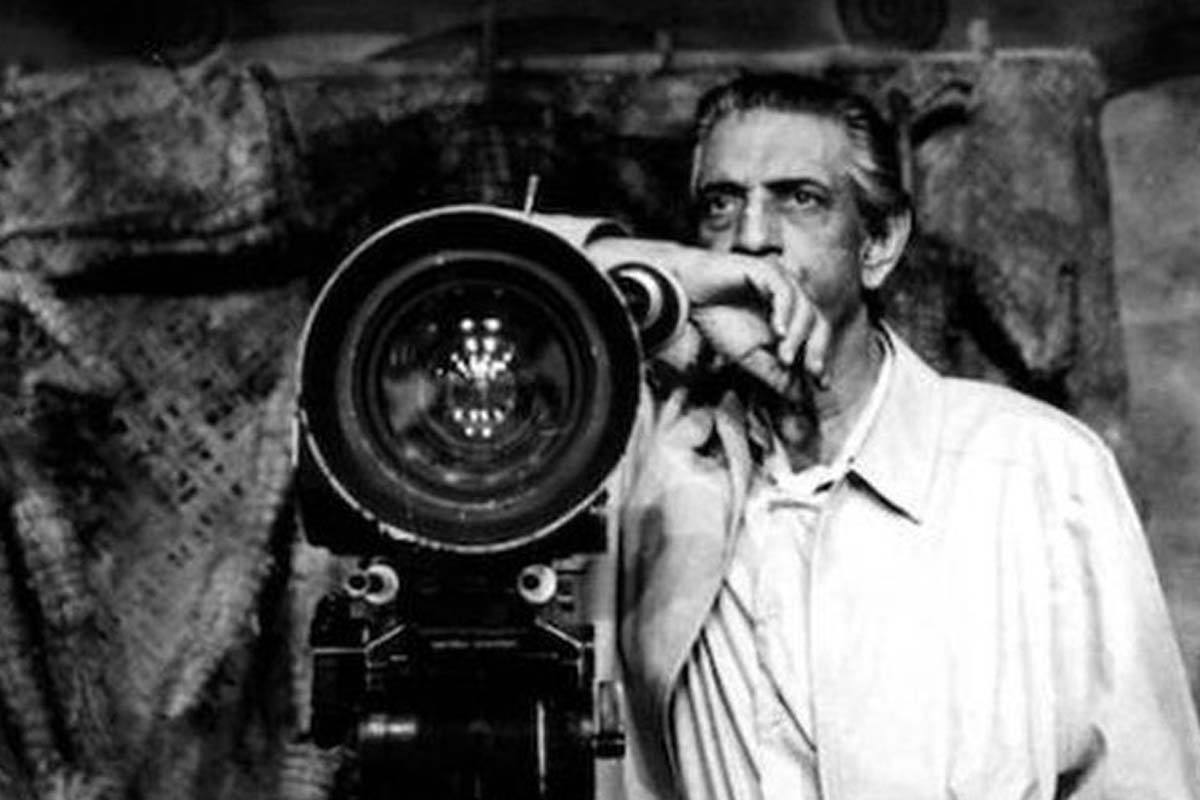

Satyajit Ray (Photo: Facebook)

The stature of Satyajit Ray (1921-92) should not be gauged by the national and international laurels bestowed upon him. It rests mainly on the admiration of millions of men, women and children keeping in mind he made films, wrote fiction, and composing music. Pather Panchali (Song of the Little Road) had run to packed houses and been critically acclaimed in Calcutta before it was hailed internationally.

His books continue to be among the best sellers in Bengali. From his early youth till his untimely death, Ray remained productive and illuminated the world of arts as very few have done. Yet, outside the Bengali-speaking areas or the sphere of film enthusiasts in India and abroad, he remains of interest as a matter of general knowledge – hardly watched, rarely read. I personally know of distinguished individuals who have not seen even one of Ray’s films. His birth centenary celebration provided an opportunity for this gulf to be bridged. Has that really happened?

Advertisement

A quick stock-taking of how he has been remembered reveals a great deal of activity from Ray’s actors, admirers and the public at large. Interesting new books have been published, and some comprehensive or academic ones, such as by Andrew Robinson and Surabhi Banerjee for example, have been revised and updated. Kolkata Municipal Corporation and Front-line magazine came out with impressive publications. Writings of this master storyteller are being brought out by the Penguin Ray Library. In Bengali, there has been an outpouring of books, journals and newspaper features focusing on various facets of Ray’s life and vision, not confined to the cinema alone.

Advertisement

The Government response, especially at the state level, has been inadequate. Central Government, through the Ministry of Information & Broadcasting, engaged itself with a year-long celebration in India and abroad, instituting ‘Satyajit Ray Lifetime Achievement Award for Excellence in Cinema’, arranging retrospectives of his films including at the Cannes Film Festival, creating a dedicated Satyajit Ray section at the National Museum of Indian Cinema at Mumbai and the like. The West Bengal Government has taken some initiatives, though largely symbolic. In film-literate Kerala, there has been some enthusiastic response. What about other states? Doesn’t Ray inspire talented directors, keen to make films within li cited budgets?

The Academy Museum of Motion Pictures in Los Angeles decided to observe the centennial with a two-part retrospective of fifteen of his films. Ray, a Hindi-language web series on Netflix, based on four of his short stories – from satire to psychological thriller – has been greeted with mixed reviews. Anik Datta’s film Aparajito (The Undefeated) chronicles the challenges faced by Ray and his co-artists while making Pather Panchali. Madhur Bhandarkar has co-produced his debut Bengali movie Avijatrik (The Wanderlust of Apu) – as a sequel to Ray’s Apu Trilogy. In Delhi, the India International Centre arranged two exhibitions, one with the costumes of Shatranj Ke Khilari (The Chess Players) and another showing the pioneering contribution of Ray in designing book covers. Raghu Rai has brought out a volume of photographs on Ray.

As can be noticed, the appreciation of Ray remains undimmed within certain sections. There seems to be a rediscovery of his diverse talents, especially among the younger generation. In fact, some of his later films about which the Western response had so far been lukewarm, as in Ganashatru (An Enemy of the People) for instance, is now being revisited.

Nevertheless, one should ask whether all these exhibitions, retrospectives, lectures and seminars, books and articles have succeeded in making Ray’s treasure reach the unreached and whether his luminous creativity is being subjected to questioning in the context of present times. While some of his lesser-known achievements – especially in music and graphic design – have been highlighted, his cinematic oeuvre remains largely confined amongst the cineastes and his prodigious but strikingly original literary output is yet to cross most linguistic barriers.

It would have been appropriate if the Central Government had brought out a commemorative stamp, as the Bangladesh Government had done, on this occasion, or would have taken the initiative of christening Ray’s birthday or the date of release of Pather Panchali as National Film or Film Director’s Day, the following few days constituting the National Film Week. Equally significant would have been actions that would spread throughout the country the gospel of good cinema and other arts where Ray made a difference.

Selecting, for example, a dozen of his films from different phases of his life, with dubbing/subtitling done in major languages of India, translating some of his best literary offerings into various regional languages, maybe under the National Translation Mission, and making them widely available through all possible channels would perhaps be worthwhile. Completing the Ray Encyclopaedia, setting up a National Ray Archive and film complexes like Nandan (as in Kolkata) at different state capitals, where his films together with those of other masters, could be continually screened should also be seriously thought of. Besides, the Government should take up with the United Nations on how best the humanistic vision of Ray could be preserved and promoted at the global level. I had suggested a blueprint of action (The Week dated 28 March 2020, and Science and Culture, September-October 2020), and many other Ray aficionados must have also offered their ideas to make his legacy more inclusive and participatory.

Ray believed in ‘art wedded to truth’ and set new benchmarks of excellence that are valued as inspirational and culturally nourishing.

He developed his own idiom to connect with the lives of people of all hues, probing deeper and deeper into conditions of human existence, while remaining firmly rooted in his own soil. Observance of Ray’s centenary would be deemed successful, and more than ceremonial, if his vast body of work is facilitated to reach far and wide, especially in our own country.

Advertisement