Ei roko prithibir garita thamao/ Aami neme jabo….. (Hey, halt, stop the speeding vehicle called the world / I’ll get down…)

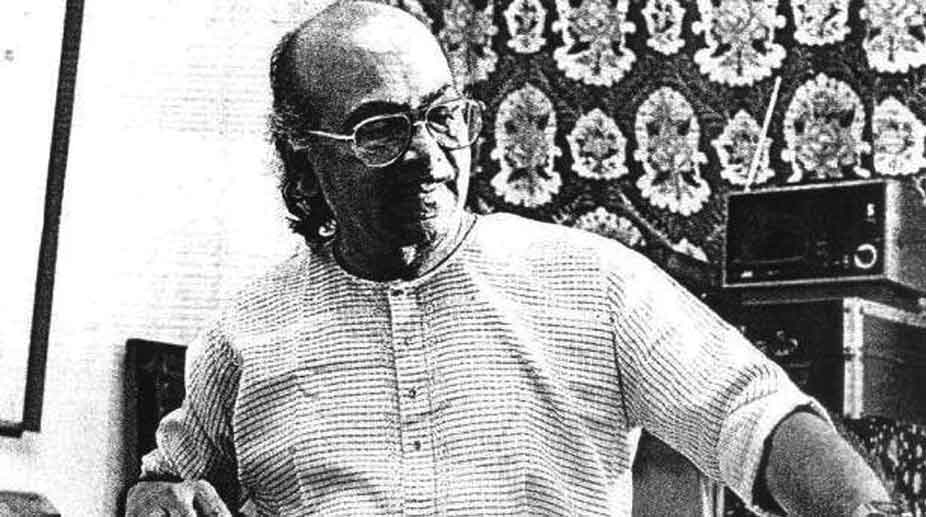

Yes the passenger who yelled like this has really got down, never to embark again. He was the genius called Salil Chowdhury. Five years away from his birth centenary, it would be inappropriate and perhaps an act of ingratitude not to remember him adequately in consideration of his immense contribution to the cause of Indian music.

Lyricist, composer, poet, singer, thinker, playwright, short story-writer and fighter for the cause of common people, Salil Chowdhury’s talents blossomed resplendently. He had a tremendous flair for instrument noting which led even an expert like Jaikishen to refer to him as “The Genius”.

Advertisement

Bollywood’s great showman Raj Kapoor once commented, ”He can play almost any instrument he lays his hands on, from the tabla to the sarod, from the piano to the piccolo”. To music connoisseurs, Chowdhury is better known for his non-conformist composure and his ceaseless and uncompromising search for perfection. Fondly called Salil-da by his countless admirers in India and abroad, he will always remain an idol to musicians and music-lovers.

Born on 19 November 1922 in Sonarpur village in south 24-parganas in West Bengal, Chowdhury spent a large part of his childhood in the Assam tea gardens where his father was posted as a doctor. Being enormously fond of his father, he grew up listening to his father’s redoubtable collection of western classical music and the folk songs of Assam and Bengal. His father was deeply patriotic, pathologically anti-British (as per Chowdhury’s reminiscences, he once broke the three front teeth of a British manager at being called a “dirty nigger”).

From early childhood Salil learnt that art should maintain a sense of social responsibility and commitment. The concept of mingling art with progressive thinking and peoples’ emancipation was injected into the impressionable mind of young Salil as he saw his father, keeping aside his high social status, organise and stage plays with tea-garden coolies and lowly-paid workers wherein the fight against exploitation by the British and the cry for a just social order was distinctly audible.

Young Salil was definitely under the influence of his father’s strong anti-British feelings and his concern and love for oppressed sections of society. In many of his songs, his support for peoples’ struggle for freeing society from oppression and exploitation was apparent.

During university days at Calcutta’s Bangabaashi College, Chowdhury’s political ideas were seen fast maturing along with his musical perceptions. Living through World War II, the massive Bengal famine and the 1940s’ bleak political scenario including the great Calcutta killings, he became acutely aware of his social responsibilities. As a response to his soul’s stirrings, he joined the IPTA (Indian People’s Theatre Association).

During those days Salil and his fellow-travellers extensively toured across cities, towns and countryside – suffering in the process acute privations including remaining without food for days together – to raise consciousness in people’s minds. He sought to do so by forceful and soulful rendition of songs, plays etc. in which the political message was clear. Between 1945 and 1951 Chowdhury composed some of his most important political songs which were rich in terms of political impact as well as textual, tonal and structural novelty proclaiming the young composer’s uniqueness. Never before had anyone in the world of music shown the courage to address the burning issues of the times.

His lyrics were imbued with a significant poetic skill embedded in an acute sense of immediacy, powerful imagery and a condign wealth of vocabulary. Chowdhury’s song structures, rhythm patterns, melodies and his unique mode of phrasing words are the most significant characteristics that set him apart as a composer.

What comes about as the most striking feature of Chowdhury’s compositions in the ‘40s and early ‘50s is his strong refusal to follow any definite pattern or be confined to any category that may be called typically ‘Salil’. Reintroduction of rhythm in the body of a single song and departure from the accepted norms of modern Bengali song structure by writing complex phrases of a single movement that would unfold themselves sometimes over several lines of lyrics were innovations unique to his creations.

Constant experiments with song structures greatly occupied his mind. His distinctive style of phrasing and scanning the melody lines along with the movements of the rhythms chosen by him along with syncopation, his relentless exploration of the possibilities of tonal expressions permanently changed the face of modern Bengali songs. A very distinctive feature of Salil Chowdhury ’s orchestration was his unique way of using rhythm, percussion and percussive instruments, clearly defining the rhythms and the rhythmic thrusts of his songs with an array of instruments – sometime a group of instruments – without being supported by a lone tabla that was had been used as the only standard rhythm instrument for a long time.

In the 1950s, Chowdhury started composing modern Bengali songs that were radically different in style, lyrics and melody so much so that Bengalis were startled. He introduced the concept of an arranger and orchestration, not seen earlier, taking a leaf from the books of Western music. He really emerged as a total composer. The numerous Bengali songs composed in the ‘50s and ‘60s by him were superb both lyrically and musically and have remained unparalleled even today. He successfully established himself as the most talented composer/lyricist after Tagore.

The new wave created by him literally swept across Bengal for at least three decades. In 1957 the Bombay Youth Coir was established by Salil Chowdhury and Ruma Ganguly to create songs of protest, patriotism and mass awareness and carry these to listeners.

The composer reached the greatest heights in his second phase and basically it started when he came to Bombay to compose for Bimal Roy’s film ‘Do Bigha Zameen’- which was an adaptation of Salil’s short story ‘Rickshawala’ written in the early 1950s. He had once planned to bring this to celluloid with his close friends Ritwick Ghatak and Mrinal Sen. In deference to Bimal Roy’s wishes, Salil Chowdury wrote the script and composed the music for ‘Do Bigha Zameen’. The outstanding film directed by Roy was released in 1953 and the rest is history.

His Bollywood sojourn thus started majestically. In the next few years he composed some wonderful and evergreen songs for films like ‘Biraj Bahu’, ‘Naukri’, ‘Parivar’, ‘Taangewaali’, ‘Awaaz’, ‘Jagte Raho’, ‘Musafir’, ‘Chhaya’, ‘Anand’ etc. He composed music for over 75 Hindi films, some 45 Bengali films, 26 Malayalam films and several Tamil, Telugu, Kannada, Gujarati, Marathi, Assamese and Oriya films. In all his creations, meticulous attention to detail, a scrupulous ear for musical content and an insatiable desire for improvisation were discernible. His exposure to wider horizons and varied experiences in the larger Bombay film industry and then the South Indian film industry brought fresh challenges which he met by expanding and sharpening his compositional acumen and during this long period Salil Chowdhury ‘s modes of composition and orchestration were seen to be influenced by Western music on the one hand and Hindustani ‘ragas’ on the other – a contrarian juxtaposition that was really delectable.

“When I started my music career I imagined the whole world of music as a very tall tower for me to climb and now after all these years I see that the tower has remained as tall as before”, said Salil Chowdhury in an interview in 1993. These words are reflective of his intrinsic qualities of humility and modesty which remained with him all his life. Even in his waning years, he never lost his sense of social responsibility. He was critical of crass commercialism patronised by the media and always stood by his values, commitment and progressive thinking. He was really a genius and one can only wonder at his unfathomable talent.

Salil Chowdhury passed away on 5 September 1995. He was a unique creator of songs of protest, of struggle, of mass awakening, of movement, of propaganda and also of romance and love with deep empathy.

The writer is a retired officer of a nationalised bank.