The Age of Human Rights, in its broader application, is the perennial age of human race and humanity right from the beginning of the human civilization. But the modern age of human rights actually started from the beginning of the second part of the 20th Century with the establishment of the United Nations in 1945.

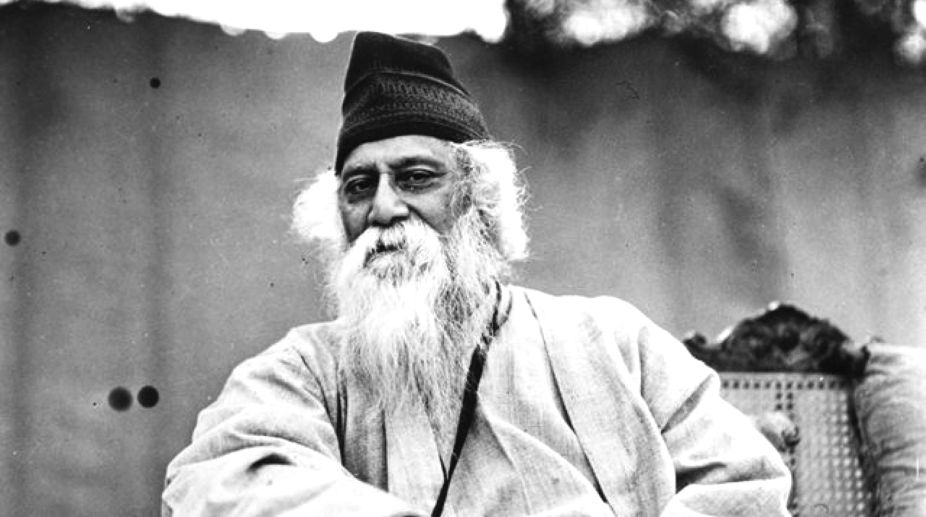

Gurudev Rabindranath Tagore died in 1941 when in his own lines-’The menacing serpents were exhaling venomous vapours all over’ in the heightened hours of the World War II. But Rabindranath remained overwhelmingly relevant in the modern-day age of human rights.

Advertisement

“Nandini – Frightening people is their prime business here. And, therefore, they have kept you in captivity as a grotesque puppet. Aren’t you ashamed of posing as a fearsome puppet?

Aside – What are you talking about Nandini?”

Every reader of Tagore’s writings would immediately recognize that the above quotation belongs to his illustrious dramatic work RaktaKarabi (The Red Oleander) which was first published in Bengali periodical Probasi in October 1922. Since then, the work has remained a piece of widely studied and researched dramatic presentation of the age-old ‘crises of humanity’. Tagore created this dramatic excellence under a unique amalgamation of the lights and shades of the real and surreal.

Twenty-two years after the publication of RaktaKarabi in book-form (1926) and seven years after the demise of Gurudev, the General Assembly of the UN adopted The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) on 10 December 1948 as its first exclusive official document on Human Rights containing thirty articles covering the whole basic gamut of the ‘crises of humanity’.

In the Preamble of the UDHR, it was pronounced “- recognition of the inherent dignity and of the equal and inalienable rights of all members of the human family is the foundation of freedom, justice and peace in the world”, and that “freedom from fear and want has been proclaimed as the highest aspiration of the common people”.

READ | Pochishe Boishakh | The story behind ‘He Nutan’, Rabindranath Tagore’s birthday song

The excruciating question of the freedom from ‘fear’ and ‘want’ was reflected often in the thinking and writings of Gurudev. The 124th song of Gitabitan Puja Parba (The Song Collection- Worshipping Section) is perhaps known to all and sundry: (O Lord) Give us new life by liberating us from fear to thy fearlessness…from poverty to thy endless wealth, from confusion to the house of Truth, from immobility to new life force, (O Lord) give us nouvelle births” (Voyhotetoboavoyamajhe etc.).

It is also illuminatingly expressed in the 221st song of the same anthology: “Thrush my fear hard, O Fearful!” (Voyere more aghatkoro etc.). There is an abundance of songs composed by Tagore challenging the elements of fear and want in the world.

In RaktaKarabi again, we find Gurudev’s sharp condemnation of slavery and human bondages as Nandini, the protagonist asks- “Can a slave ever practice respect for others?” It amply contains the cruel resonance of the anguishes of chained humanity which more metaphorically expresses the states of modern age political and economic slavedoms.

The UN Declaration of Human Rights, inter alia, states that no one shall be held in slavery or servitude; slavery and slave trade shall be prohibited in all their forms. The practice of slavery was officially abolished much earlier in 1864 in the USA while the first International Slavery Convention of 1926 held under the aegis of the first world-government of the League of Nations was last amended by the UN Protocol of 1953.

In its very first Article, the convention defined ‘slavery’ as “the status or condition of a person over whom any or all of the powers attaching to the right of ownership are exercised”.InRaktaKarabi, the intense admonition of Nandini against slavery contains the high resonance of the cruelty implicit in the right of ownership over a human person.

Such a right of ownership is an absolute violation of human rights and the principles of humanity. Prof. VS Waghule, a senior lecturer in the Government Law College, Mumbai, while explaining the term ‘humanity’ in his article Custodial Violence and Human Rights, observed – “What is humanity? This one word has many colourful and meaningful shades.

If every human being, specially the one having power, either political, executive, judicial or police, understood and strictly followed humanity and made it a life style, then the question of torturing the dignity of any human being would not arise at all.”

Human Rights today, a number of years after the adoption of the UDHR, remains the only realizable reality of a true religion of man. The spiritual manifestations of human rights gradually surfaced in the world in the process of the transformation of humanity into the higher designs of Humanism.

The collection of Gurudev’s essays and lectures on spiritual philosophy and practical religion of man contained in two books viz. Dharma (The Religion) and Manusher Dharma (The Religion of Man) were published in 1909 and 1933 respectably. These two book-collections along with Santi Niketan (1909) in two parts are of boundless human rights values and these should be included in the compulsory studies of human rights education all over.

In the thoughts Rabindra nath, the qualities of humanity are easily elevated to the level of divinity, where actually the myriad elements of humanity, world-realisation and the total oneness of the creation finely mingle into a complete form of an ideal state of the superior human existence.

In his essay titled Biswa Bodh (The World Realization) contained in the second part of Santi Niketan, Gurudev deliberated – “As Europe embraced the aspirations of imperialism to be the greatest benediction (for the world) and indulged in achieving this in many bizarre ways, India considered the achievement of world-realisation as the highest good for the humanity and for activating the mankind towards this goal, engaged her efforts from different directions.

This is the ‘higher effort’ (sadhana) of man towards the ‘higher humanism’ (swattikata) – the cravings for the fulfillment and total elevation of the inner-being and the fact that this unbound inner-being led world realisation remains as the absolute Truth for India should be remembered today with full pride and pleasures (by all of us).”

The four basic rights – life, liberty, equality and dignity – expounded as inherent and inalienable in human rights jurisprudence, are abundantly focused in the countless writings, poems, dramas, novels, short stories and even in the paintings of Gurudev. In the back-drop of his travel in Soviet Russia, he wrote in RussiarChithi (The Letters from Russia-1931) – “Dictatorship is a veritable bane – I do agree and also believe that it has been committing much tyranny in today’s Russia. Its negative aspects rest on the forceful imposition of power (on people) that amounts to committing sins”.

In another letter contained in the same collection, he wrote- “An iron-modeled political system (in Soviet Russia) shall not survive: It shall fall apart like a house of cards.” Sixty years after, the world witnessed with eyes wide open how the prophesy of the sage-poet came true with the collapse of the USSR.

In this context, it might as well be taken into account that the world human rights movement with its capital resource in the ideals of ‘humanism’ acquired global recognition with the adoptions of the UN Charter (1945) and the UDHR (1948), while at the relevant time-frame of history, the ideology of Radical Humanism expounded by MN Roy, once a close aide of Lenin, virtually challenged some vitally inherent principles of Marxism.

Rabindranath could not witness the creation of today’s United Nations in the aftermath of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the ever-proliferating vast working missions of the UN for the causes of human rights across the world, especially in the poor, war-torn countries of the third world. The development and progress of human rights so far achieved under UN endeavours have been academically classified into three generations of human rights and strewn through hundreds of human rights documents, treaties and laws.

Still we find, at times to our chagrin, striking notes of a visionary precursor of the UN Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) 1979 in Tagore’s dance-drama Chitrangada; International Convention on Civil and Political Rights 1966 (Article 9-the right to liberty and security of person and right against arbitrary arrest and detention) in dance-drama Shyama, the Convention on the Rights of the Child 1989 in the short story Fhatik and in many more creations of Gurudev.

As an officer of Kolkata Police, I had the opportunity to work with the International Police Task Force of the UN Mission in war ravaged Bosnia & Herzegovina of the former Communist Republic of Yugoslavia (2000-2001) where it appeared to the utter dismay of an Indian Peacekeeper that Tagore’s writings, particularly Gitanjali (The Song Offerings) remained a great spiritual source of survival from imminent onslaught of insanity for many Bosnians during the long siege of Sarajevo, both victims and forced combatants of the war.

Later, during the days in the Francophone UN Mission in Ivory Coast (Cote D’Ivoire in 2005-2006)), this writer was doubly astonished when in course of a long jungle patrol with a UN army detachment, the Commander Capitan Mohammad Nabil of Morocco Contingent went on reciting Gurudev’s famous poem “Africa” in its full French version which instantly reminded us all of the UN Declaration on Granting Independence to Colonial Countries and Peoples, 1960.

The police being a close concern for both protection and violation of Human Rights, it may well be an interesting fact that Gurudev was a keen observer of the policing system of his life and times and in one of his short rhymes collection KhapChara (The Unsynchronized), he wrote the rhyme Raj Byabastha (The System of King’s Administration):

Maharaj Bhoye Thake PulisherThanate,

Ain Banay Joto Pare Na Ta Manate,

Char Fere Take Take, Sadhu JadiChara Thake

Khoj Pele Nripatire Hoy Taha Janate,

Raksha KariteTaakeRakhe Jail Khanate.

[The King himself is afraid of the police station,

All the laws he made are not in implementation,

The spies of police move for opportunities

If the pious men are living in the vicinities,

The information must be sent to King’s Trail,

And for his safety, police keep the pious in Jail.]

The writer is Guest Faculty in Human Rights at the Central Detective Training Institute, Kolkata, former Assistant Commissioner of Kolkata Police and former United Nations Human Rights Officer in Bosnia and Technical Adviser of UNPOLICE in Ivory Coast. The translations in this text are by him.