India and Ukraine~II

Two other major powers in the Indo-Pacific are Australia and New Zealand.

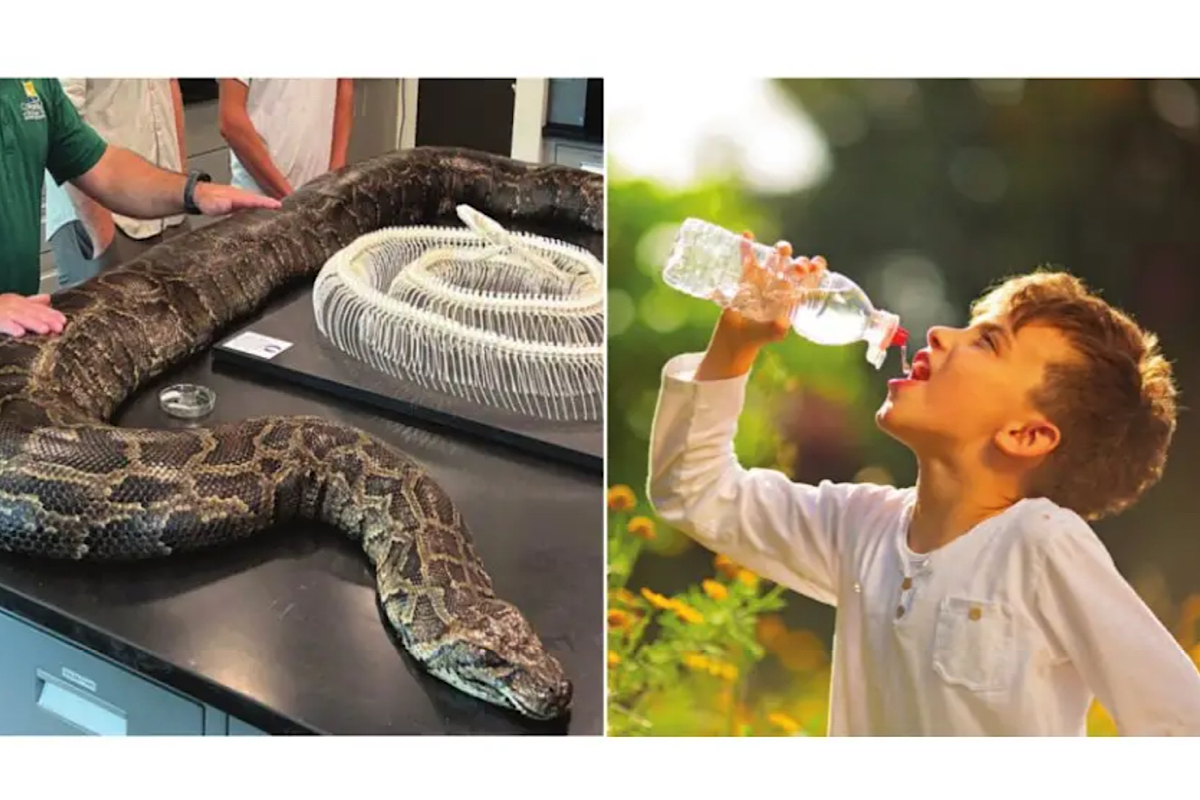

The researchers studied more than 4,600 pythons and found that reticulated and Burmese pythons, in particular, required less food to produce, say, a pound of meat compared to conventional farm products such as chicken, beef, pork, salmon etc. Pythons grow rapidly to reach the ‘slaughter weight’ within a year after hatching.

SNS | New Delhi | May 11, 2024 7:00 am

Representation Image

Aresearch team comprising scientists from Macquarie University in Australia, Oxford University, UK, the University of Adelaide, Australia, the University of Witwatersrand, South Africa, and the Vietnamese Academy of Science and Technology, did a focussed study on reticulated pythons (Malayopython reticulatus) and Burmese pythons (Python bivittatus) and reported that snake meat is not only a good source of protein but also the best alternative for sustainable living. This appeared in the journal Nature’s 14 March 2024 issue under Scientific Reports (DOI:10.1038/s41598- 024-54874-4).

The researchers studied more than 4,600 pythons and found that reticulated and Burmese pythons, in particular, required less food to produce, say, a pound of meat compared to conventional farm products such as chicken, beef, pork, salmon etc. Pythons grow rapidly to reach the ‘slaughter weight’ within a year after hatching. According to Dr. Natusch, the first author of the paper, “pythons outperform all mainstream livestock chicken and cattle” when food to protein conversion is considered. Eating snake meat is nothing new. Snakes have long been consumed in Southeast Asia and China as a high-protein, lowsaturated fat food source. Hong Kong is famous for its snake soup which has been consumed for over 2,000 years in China. Scientists are not expecting the consumption of snake meat to be accepted worldwide easily, except maybe in some parts of Asia.

Advertisement

But they are batting for it for serious environmental reasons ~ from the point of view of water conservation. When we consume one kg of meat, we are consuming 16,000 liters of water unknowingly ~ the amount of water needed to raise livestock to get that amount of meat. Or, when we have a cup of coffee in the morning, we consume 150 litres of precious water from the earth unknowingly. The cotton T-shirt that we wear is equivalent to about 2,000 litres of water wrapped around us. It was John Anthony Allan of the University of London who invented a method of estimating the amount of fresh water needed to produce different commodities, a metric he has christened ‘virtual water’. The amount of virtual water consumed through food and clothing is many times more than the amount that we consume for drinking and household purposes.

Advertisement

India exports about 20 million kg of coffee annually, and is, therefore, responsible for exporting about 420,000 million litres of virtual Indian water with it. Countries like Argentina, Brazil and the US export billions of litres of virtual water every year while countries like Egypt, Italy and Japan import billions of virtual water. It was Professor Arjen Hoekstra who introduced the concept of ‘water footprint’ as a metric to measure the amount of water consumed to produce goods and services. In other words, the water footprint helps to comprehend how much water people consume daily in their lives, and is similar to the ideas of ‘carbon footprint’ or ‘ecological footprint’ that most of us are familiar with. It is ironic that while we are so concerned about greenhouse gases and their impact on the environment, we are more or less oblivious to freshwater consumption and its impact on the environment and population.

In a world where one in every five persons does not have access to fresh water, and particularly when the demand for water resources in the whole world is increasing, the issue of water footprint needs to be taken seriously. The earth is indeed a closed system and the water cycle ensures that as a whole, it neither loses nor gains water, and so the water will never be depleted. It is jokingly said that it is quite possible that the water that you drank just now was once used by Mama Dinosaur to give her baby a bath! Critics have legitimately questioned the need to conserve water, given that all that we use will be returned. While that is certainly true for a closed system, with the dichotomy of increasing population and finite resources, resource management is crucial to maintain the minimum requirement of water per individual.

An analogy may be seen in inheriting a fixed amount of money that can be used only for the benefit of one’s children. However, the amount of money spent per child (per capita) will diminish if the number of children increases, and with more progeny, a time will come when money available per child will fall below what is needed to fulfill their basic needs. Being a little conservative in using water will help to avoid, or at least delay, any future catastrophe. The water footprint of a country is also an indicator of the efficiency of the nation’s water management and agricultural practices. According to the report of the World Health Organization (WHO), water scarcity impacts 40 per cent of the world’s population and 700 million people are at risk of being displaced as a result of the water crisis by 2030. By 2040, almost 1 in 4 children will live in an area of extremely high water stress.

Among the many options suggested by WHO to mitigate the water crisis, attitudinal change is a prime one. Many conventional livestock fail to satisfy the criteria for sustainability, and there is an urgent need to explore alternatives. Snakes are probably the best alternative. Snakes require minimal water and can live with the dew that settles on their scales in the morning. They also need very little food and live off rodents and other pests that attack food crops.

Although large-scale python farming is common in Asia, environmentalists suggest that the same is needed in other parts of the world too. Considering the potential benefits, this will be a bold move and the project requires encouragement from all corners of society. In the distant future, if a snake burger is served instead of a meat burger in a restaurant, do not get perplexed but think of the precious snake that helped save the enormous amount of precious water of Nature.

SUPRAKASH CHANDRA ROY The writer is a Member, National Commission of History of Science, INSA and was Editor-in-Chief of the journal Science and Culture for about two decades

Advertisement

Two other major powers in the Indo-Pacific are Australia and New Zealand.

Skipper Pat Cummins, experienced quick Josh Hazlewood, and all-rounder Cameron Green are among the inclusions as defending champions Australia announced a full-strength squad for the ICC World Test Championship final against South Africa at Lord’s, starting June 11.

The Australian electorate has spoken decisively. In what can only be described as a stunning political outcome, Prime Minister Anthony Albanese’s Labour government has secured a commanding second term, expanding its majority in Parliament and defying the global trend of incumbent fatigue.

Advertisement