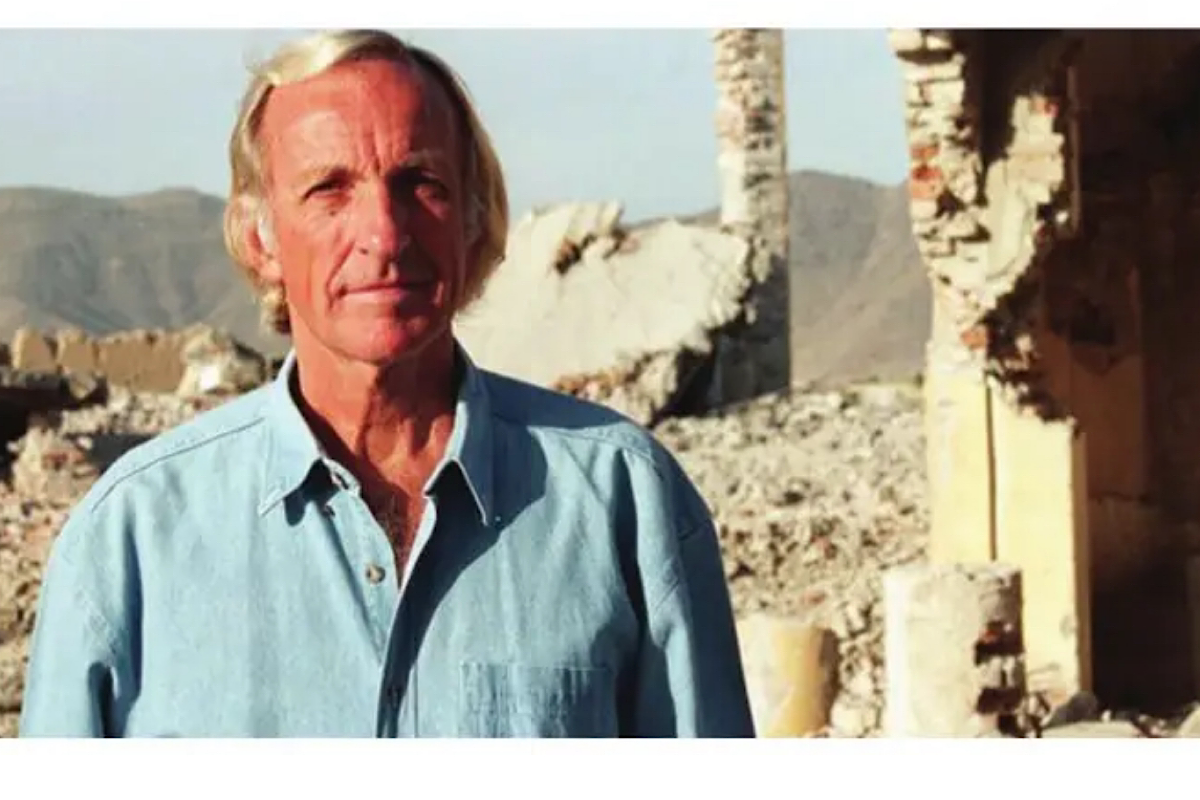

John Pilger, who passed into history on 31 December 2023, remains an iconic personality for those who knew, read and were influenced by him. Millennials unaware of his vast writings and films ~ fiery, forceful, precise, evidencebased on-the-ground reporting ~ may benefit from excerpts from his archives (held at The British Library), exemplifying independent journalism.

On 3 August 2020 to mark the 75th anniversary of Hiroshima’s atomic bombing, Pilger described reporting from five ‘ground zeros’ for nuclear weapons ~ from Hiroshima to Bikini, Nevada to Polynesia and Australia. “When I first went to Hiroshima in 1967, the shadow on the steps was still there. It was an almost perfect impression of a human being at ease: legs splayed, back bent, one hand by her side as she sat waiting for a bank to open.

Advertisement

At a quarter past eight on the morning of August 6, 1945, she and her silhouette were burned into the granite. I stared at the shadow for an hour or more, then I walked down to the river where the survivors still lived in shanties,” he wrote. He met Yukio, whose chest was etched with the pattern of the shirt he was wearing when the bomb was dropped. Yukio described a huge flash over the city, “a bluish light, something like an electrical short”, after which wind blew like a tornado and black rain fell. “I was thrown on the ground. Everything was still and quiet, and when I got up, there were people naked, not saying anything. Some of them had no skin or hair.

I was certain I was dead.” Nine years later when Pilger returned looking for Yukio, he was dead from leukaemia. Pilger wrote, “No radioactivity in Hiroshima ruin” said The New York Times front page on 13 September 1945, a classic of planted disinformation. “General Farrell,” reported William H. Lawrence, “denied categorically that [the atomic bomb] produced a dangerous, lingering radioactivity.”

Only one reporter, Wilfred Burchett, an Australian, braved the perilous journey to Hiroshima in the immediate aftermath of the atomic bombing, in defiance of Allied occupation authorities, which controlled the “press pack”. “I write this as a warning to the world,” reported Burchett in the London Daily Express of 5 September 1945. Sitting in the rubble with his Baby Hermes typewriter, he described hospital wards filled with people with no visible injuries who were dying from what he called “an atomic plague”. For this, his press accreditation was withdrawn, he was pilloried and smeared. His witness to the truth was never forgiven, reported Pilger. Palestine is Still the Issue, wrote Pilger on 10 July 2017. “When I first went to Palestine as a young reporter in the 1960s, I stayed on a kibbutz.

The people I met were hard-working, spirited and called themselves socialists. I liked them. One evening at dinner, I asked about the silhouettes of people in the far distance. “Arabs”, they said, “nomads”. The words were almost spat out. Israel, they said, meaning Palestine, had been mostly wasteland and one of the great feats of the Zionist enterprise was to turn the desert green. They gave as an example their crop of Jaffa oranges, which was exported to the rest of the world. What a triumph against the odds of nature.”

“It was the first lie,” said Pilger. “Most of the orange groves and vineyards belonged to Palestinians who had been tilling the soil and exporting oranges and grapes to Europe since the eighteenth century. The former Palestinian town of Jaffa was known by its previous inhabitants as “the place of sad oranges”. On the kibbutz, the word “Palestinian” was never used. Why, I asked. The answer was a troubled silence. All over the colonised world, the true sovereignty of indigenous people is feared by those who can never quite cover the fact, and the crime, that they live on stolen land.”

“Denying people’s humanity is the next step ~ as the Jewish people know only too well. Defiling people’s dignity, culture and pride follows as logically as violence. In Ramallah, following an invasion of the West Bank by late Ariel Sharon in 2002, I walked through streets of crushed cars and demolished houses, to the Palestinian Cultural Centre. Until that morning, Israeli soldiers had camped there. I was met by the centre’s director, the novelist Liana Badr, whose original manuscripts lay scattered and torn across the floor.

The hard-drive containing her fiction, and a library of plays and poetry had been taken by Israeli soldiers. Almost everything was smashed, and defiled. Not a single book survived with all its pages; not a single master tape from one of the best collections of Palestinian cinema. Soldiers had urinated and defecated on the floors, on desks, on embroideries and works of art. Liana Badr had tears in her eyes, but she was unbowed.

She said, ‘We will make it right again’.” Pilger was at the forefront of recording “what enrages those who colonise and occupy, steal and oppress, vandalise and defile is the victims’ refusal to comply. And this is the tribute we all should pay the Palestinians. They refuse to comply. They go on. They wait ~ until they fight again. And they do so even when those governing them collaborate with their oppressors.

In the midst of the 2014 Israeli bombardment of Gaza, the Palestinian journalist Mohammed Omer never stopped reporting. He and his family were stricken; he queued for food and water and carried it through the rubble. When I phoned him, I could hear the bombs outside his door. He refused to comply.” “For more than 40 years, I have recorded the refusal of the people of Palestine to comply with their oppressors: Israel, the United States, Britain, the European Union. Since 2008, Britain alone has granted licences for export to Israel of arms and missiles, drones and sniper rifles, worth £434 million.

Those who have stood up to this, without weapons, those who have refused to comply, are among Palestinians I have been privileged to know,” he said. On 21 September 2017, in The Killing of History, wrote Pilger, “One of the most hyped ‘events’ of American television, The Vietnam War, has started on the PBS network. The directors are Ken Burns and Lynn Novick. Acclaimed for his documentaries on the Civil War, the Great Depression and the history of jazz, Burns says of his Vietnam films, ‘They will inspire our country to begin to talk and think about the Vietnam war in an entirely new way’.

“In a society often bereft of historical memory and in thrall to the propaganda of its ‘exceptionalism’, Burns’ ‘entirely new’ Vietnam war is presented as ‘epic, historic work’. Its lavish advertising campaign promotes its biggest backer, Bank of America, which in 1971 was burned down by students in Santa Barbara, California, as a symbol of the hated war in Vietnam. Burns says he is grateful to ‘the entire Bank of America family’ which ‘has long supported our country’s veterans’. Bank of America was a corporate prop to an invasion that killed perhaps as many as four million Vietnamese and ravaged and poisoned a once bountiful land.

More than 58,000 American soldiers were killed, and around the same number are estimated to have taken their own lives.” Pilger, viewing the first episode in New York, observed, “It leaves you in no doubt of its intentions right from the start. The narrator says the war ‘was begun in good faith by decent people out of fateful misunderstandings, American overconfidence and Cold War misunderstandings’. The dishonesty of this statement is not surprising. There was no good faith.

The faith was rotten and cancerous. For me ~ as it must be for many Americans ~ it is difficult to watch the film’s jumble of ‘red peril’ maps, unexplained interviewees, ineptly cut archive and maudlin American battlefield sequences. In the series’ press release in Britain – the BBC will show it – there is no mention of Vietnamese dead, only Americans. ‘We are all searching for some meaning in this terrible tragedy,’ Novick is quoted as saying.

How very postmodern.” Unafraid to share his observations, Pilger said, “All this will be familiar to those who have observed how the American media and popular culture behemoth has revised and served up the great crime of the second half of the twentieth century: from The Green Berets and The Deer Hunter to Rambo and, in so doing, has legitimised subsequent wars of aggression. The revisionism never stops and the blood never dries.

The invader is pitied and purged of guilt, while ‘searching for some meaning in this terrible tragedy’. Cue Bob Dylan: ‘Oh, where have you been, my blueeyed son?’ ” “I thought about the ‘decency’ and ‘good faith’ when recalling my own first experiences as a young reporter in Vietnam: watching hypnotically as the skin fell off Napalmed peasant children like old parchment, and the ladders of bombs that left trees petrified and festooned with human flesh. General William Westmoreland, the American commander, referred to people as ‘termites’,” recorded John Pilger to whom generations are indebted.

(The writer is a writer researcher on history and heritage issues and former deputy curator of Pradhanmantri Sangrahalaya)