A palpably singular interpretation of history has been encapsulated by some scholars in the averment that mankind has progressed through heresy, not piety. Actually, the import of this perception lies in the ubiquitous process of dialectical movement propelled by the forces of thesis, antithesis and synthesis.

Now, let us have a look at etymology. Heresy is staunch criticism of things and values that are traditional. It seeks to trample upon the established order of society or of religion to usher in a different and new world. It boils down to non-cooperation, rejection of and resistance to the prevalent ways of life and religion. But without cooperation, without some kind of accommodation of opposing views there cannot be any advancement, and forward movement. Mutual acceptance and absorption have been the sine qua non of progress. This has been universally acclaimed by observers and historians.

Advertisement

Piety is an altogether different matter. It connotes adherence to and respect for the established canons of society and religion. It arguably hinges on faith. Faith is the result of steadfast obeisance to an ideal and an earnest essay to translate that ideal into reality through rigorous and regulated practice. To accomplish this submission to a superior intelligence, a calm and sedate temperament, wisdom and tolerance are needed.

Unfortunately, a dig at the faithfulness to a prescient human being with deep insight into the nature of things, profound farsightedness and uncommon plasticity of mind has been aimed at by some analysts. The aspersion is that free thinking has disappeared with the advent of gurudom which has generated blind faith in the master and blind obedience to authority. It is a poignantly preposterous evaluation of historicity, one that is totally non-existent.

Viewed in the general and broad sense of the terms, some sort of gurudom entailing the process and practice of imparting education to the disciples by the capable masters has been in vogue since the inception of civilisation and cultural pursuit. Lord Buddha propagated the idea of free thinking ~ Atma Deepo Bhabo. Long before Buddha disseminated his teachings the seekers of knowledge, the disciples in the Vedic age went to gurugriha, practised continence, hard work and learnt to live a healthy and fruitful life and acquired knowledge of the highest order ~ Atmanam Biddhi.

They obeyed the guide with deep veneration, acknowledging his unquestioned authority. Now, the faith in the master is not the blind faith as is loosely categorised. The faith is inculcated to know Satyam. Trust in the teacher is the methodology to attain divinity to savour the highest bliss and to be truly luminous with Prajna. They submitted to authority to know Brahman.

In the unique parlance of Sri Aurobindo, the profane misconstrues it to be blind faith, the initiate considers it as the inviolable condition of truth-perception. The authority of the teacher is Sraddha for superior knowledge. The Shastra prescribes that one has to be attached to and associated with satyadarshi and express one’s views boldly and independently. “Be Azad,” said the Swami. One lesson the great masters taught their disciples is Brajnanam Brahma.

Thus, Basistha the Rishi of the Vedic era taught Rama the king of Ayodhya one lesson in particular ~ to achieve gnana without which Bhakti is of no avail. The Gita insisted that one should acquire knowledge from the taattadarshi through obeisance, through questioning and through service. Tad biddhi pranipatena, pariprosnena, sebaya. Debguru Brihaspati in the Purana has startlingly said: Kebalam sashtramasritya, na kartabya baniraya juktihina, bicharena dharmahani, prajayate. Swamiji quoted the scriptures saying if reason demands, one should even blame the guru ~ Dosobachya Gururopi.

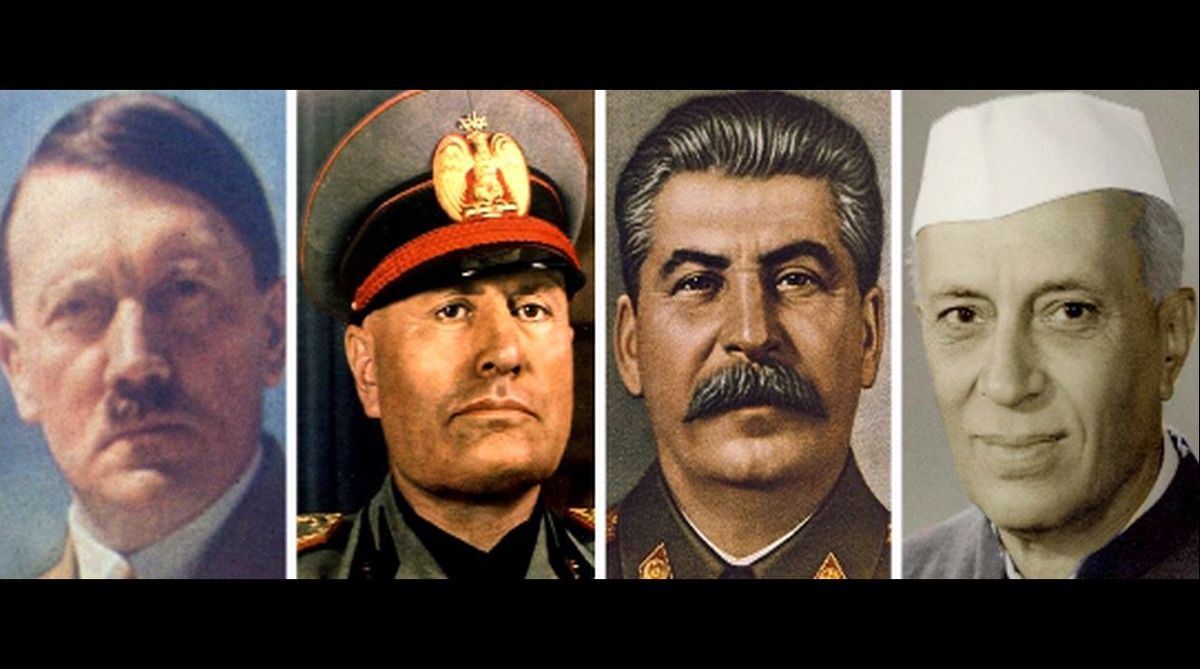

In the tangled web of the world of politics, authority signifies another facet and assumes an altogether different dimension. A Hitler or a Stalin, the ruthless dictators of a totalitarian regime commanded unquestioned authority without being adorned with the decorative strip of religion or with a religio-political flavour. People offered a need of unconditional submission to their will not out of sraddha or faith but out of cold and crippling fear. Even in a bubbling democracy, a popular leader enjoys unbridled power dangling before the people the gleaming prospect of abundant happiness, and prosperity. This unchallenged power is generated by overriding extraneous circumstances.

Such a leader is pitch-forked to the summit of glory by the fervid expectation of the people and adroit manipulation of the leadership to maintain that frenzied level of hope. ‘People’, as a cynical political scientist has observed, ‘are sheep-minded, ape-minded and wolf-minded’. Such a contention is of course, largely skewed. But swayed by untrammeled anticipation, they are led like a flock of sheep by the wily shepherd.

The sheep-mindedness gets the upper hand in the public psyche and the leader assumes an unassailable position. To cite an example, Jawaharlal Nehru, as India’s first Prime Minister. had stopped the army from driving out the Hanadars of Pakistan immediately after independence brushing aside all advice. This generated the canker of the Kashmir issue ~ an ineradicable carcinoma in the body politic. Again, riding on the crest of over whelming popularity, a swashbuckling Nehru, the harbinger of peace, spoke of throwing the army in Connaught Place.

As early as 1950, Sri Aurobindo had cautioned the country, saying “Mao will attack India”. The word of caution was unheeded. The result was a crushing defeat, a seething humiliation at the hands of the Chinese in October 1962 and the persistent incubus of incursions thereafter.

The refrain among the politicians surrounding Nehru, as has been mentioned by a learned professor in these columns was that “Panditji knows best’. There was no voice of protest, no murmur of demur before the debacle hit the country. It becomes patently clear that faith in authority either in a democracy or autocracy is not necessarily related to the religio-political hybrid. Neither Hitler nor Mussolini nor Stalin nor for that matter Jawaharlal Nehru were decked with religious frills to exercise their power.

Reverting to the main issue, perpetual interaction between piety and heresy or between tradition and freedom is an irreversible phenomenon of social dynamics. Freedom either in thought or in action, to be truly meaningful and conducive to progress, must spring from the bedrock of tradition and have its roots deeply embedded in the prevalent ethos. An optimal blend of piety and iconoclasm is the saving grace and safety-valve of a vibrant nation in course of its onward march.

The writer is a retired IAS officer.