The end game was played when political power was transferred to India in 1947. In the name of Independence, Dominion Status was granted to us. H V Hodson, the British advisor to the Viceroy of India, said in his ‘The Great Divide’ that Dominion Status meant full nationhood within the British Commonwealth. Hodson defended the British perspective on dominion status and it is quite understandable that he would avoid any explanation as to how the Dominions could become free nations despite their common allegiance to the British Crown. But, how did our leaders accept Dominion Status as independence and decide to join the Commonwealth? Britain’s Imperial strategy underlying membership of the Commonwealth was revealed long before 1947 in the Balfour Report. The Balfour Report was prepared by the Committee on Inter-Imperial Relations at the Imperial Conference held in London in 1926.

The Report was named after a British Cabinet Minister, Arthur Balfour. It claimed to have developed a new concept of relations between Britain and the Dominions. It pointed out that Britain and the Dominions would be autonomous communities within the Empire. They would be equal in their relationship to one another. The members of the British Commonwealth would remain united by a common allegiance to the British Crown. ‘British Commonwealth’ became ‘Commonwealth of Nations’ after the London Declaration, a declaration issued by the Commonwealth Prime Ministers’ Conference in London in 1949. It was propagated widely that the London Declaration ushered in the birth of a new Commonwealth which was no longer an exclusively British organisation, but a free association of an international organisation that included even republics as its members. A careful examination of the declared objectives of the so called ‘new Commonwealth’, however, reveals that this was not substantially different from the objectives laid down in the Balfour Report.

Advertisement

The Balfour Report emphasised that Britain and the dominions were autonomous and equal in their relations. Theirs would be a free association within the British Commonwealth with a common allegiance to the British Crown. Was this status altered by the London Declaration? There was only the change of name from British Commonwealth to Commonwealth of Nations and inclusion of republics in the Commonwealth. Everything else remained exactly the same. Nehru signed the declaration in 1949. Even before signing the Declaration, he had expressed his willingness to accept the British King as the permanent head of the Commonwealth. Mountbatten, in his letter of 25 October 1948, to Noel-Baker, Secretary of State for Commonwealth Relations informed “… Stafford came down with the idea of asking India to accept the King as the fountain of honour for the Commonwealth, Nehru gladly accepted this…’’ This explodes the myth that Nehru was initially opposed to the idea of joining the Commonwealth, an organisation that had the British monarch as its head.

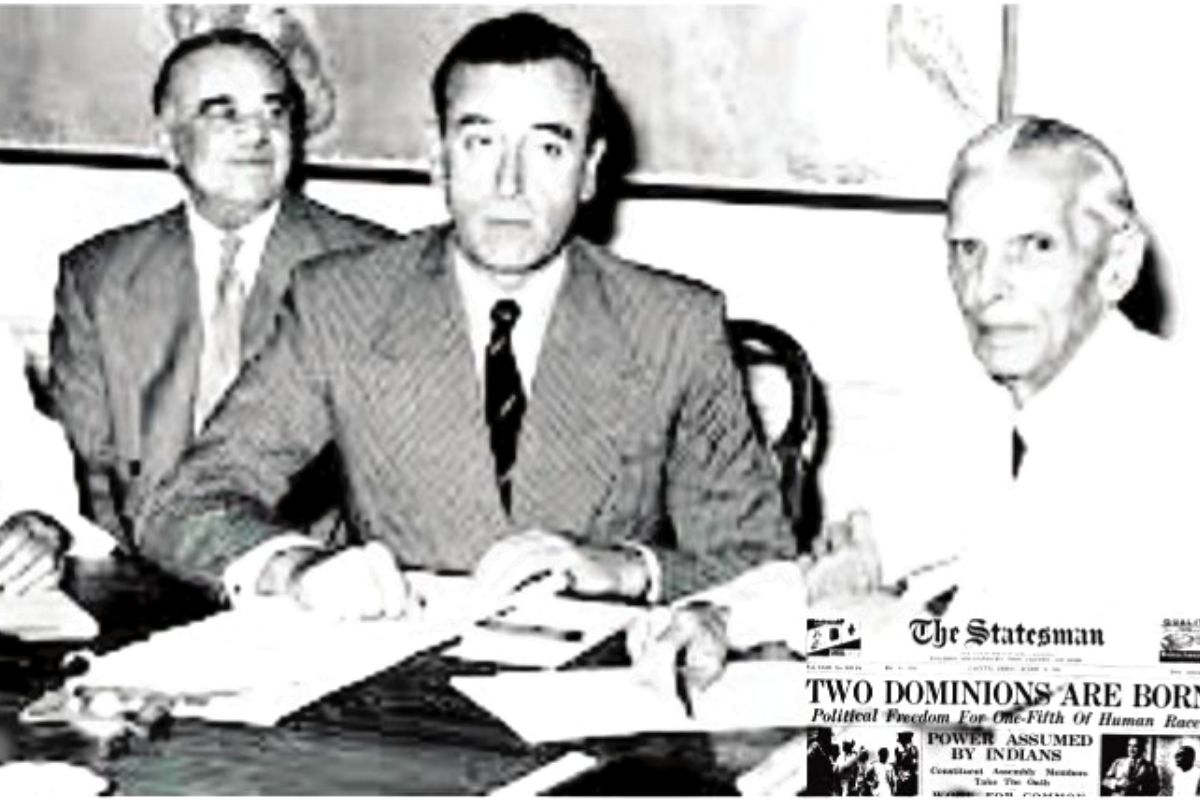

On the other hand, his eloquent defence of complete independence is hardly convincing because he never opposed the Indian Independence Act 1947 in terms of which India was made a Dominion. Let us now examine how the Indian Independence Act stipulated that the Indian Dominion would be subordinated to the British Crown. The Indian Independence Act 1947 was passed in the British Parliament. It stated in chapter 30, section 1.—(I), “… from the fifteenth day of August, nineteen hundred and forty-seven, two independent Dominions shall be set up in India, to be known respectively as India and Pakistan.’’ It clearly shows that we were given only Dominion status and not full independence. The expression Independent Dominion would seem absolutely meaningless if one goes through the shocking text of Section 2.—(I.) of the same chapter. 2.—(I) says, “… the territories of India shall be the territories under the sovereignty of His Majesty, which immediately before the appointed day [i.e. 15 August 1947] were included in British India…’’

In other words, the territories of India which were, before 15 August 1947, included in British India, would be under the sovereignty of the British Crown. If it were an innocent provision describing the status of former British Indian Territories, why did Britain repeal this by the Statute law (Repeals) Act 1976? The Indian leaders, impatient to come to power, accepted it as our independence. One would like to know why there was no hue and cry over this hidden agenda of the Transfer of Power. For years together, the leaders who surrendered to Britain’s plan of control were in power. They relentlessly propagated their sole proprietorship of the freedom struggle.

The communists did criticise the nature of freedom we achieved, but they did not make any attempt to expose the agenda underlying the Indian Independence Act 1947. They focused chiefly on economic issues. Other organisations’ positions were insignificant from the national perspective. They could not put up any effective challenge to the official propaganda. It is not true that people of India did not develop the spirit of nationalism to move from Dominion status to complete freedom. Over the years, despite the officially sponsored propaganda, they cherished the memory of the INA revolt and Naval Mutiny. The revolutionaries have always been their heroes. But unfortunately, such narratives always remained beneath the surface. The spirit is there. It has to be rekindled so that it can banish for good whatever colonial mind-set is still left.

(Concluded)

A version of this story appears in the print edition of the September 8, 2022, issue.

The writer is former Head of the Department of Political Science, Presidency College, Kolkata