From handloom silks of Bengal to dragon-embossed tables of Ladakh, India is a treasure chest of indigenous handicrafts which have won it a coveted place in the cultural heritage of the world. Every sculpted jewel box and embroidered shawl has deep roots in the land it originates from. Entrenched in the history of a place, traditional artifacts are not just great souvenirs ~ they are mini periscopes into a region’s geography and culture.

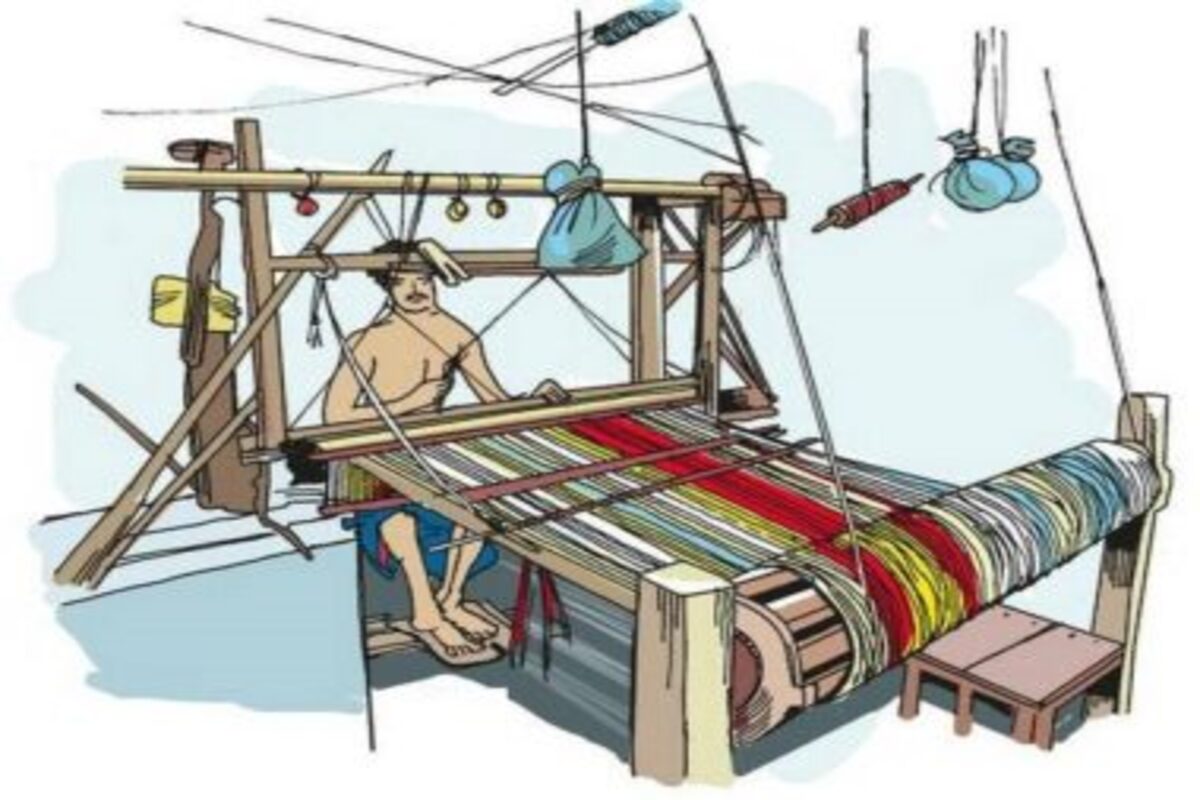

Handloom is one of the most exquisite textile traditions of India, and hand-spun and woven fabrics were for centuries an integral part of India identity. The towns and villages in India’s handloom heartland are home to some of India’s finest weaving styles. You can observe in a magical trance as reels of yarn are spun, dyed, and transformed into spectacular pieces of art.

Advertisement

Generations of nervous brides have been reassured by the silken rustle of a Banarasi sari. And yet, sadly weavers of such heirlooms have found it harder and harder to survive. The few that still ply the trade work on traditional wooden jacquard looms. Watching them painstakingly weave the zari, usually made of real silver, is a rare treat. The textile’s floral motifs, peacocks, paisleys, and chintz trace their roots to ancient and medieval times, the Mughal reign, and the colonial rule in India.

A complex social structure and a rich cultural life led to an elaborate textile vocabulary. Religious traditions also demanded the finest fabric to clothe the deities. Under the patronage of kings and queens, these traditions evolved further to produce grander, more elaborate textiles.

Weaving in India dates to 500 B.C. and flourished during the Mughal period from the early 16th to mid-18th centuries. For centuries India was a hub for the silk trade. Under the Mughals, Indian weavers worked alongside masters from Persia and Central Asia, assimilating new skills in weaving and ornamentation. The Naqshbandi art of tying designs into looms emerged from this cultural contact as did the floral designs of Kashmir.

While the origin of handicrafts is rooted in history, we have to link their future with the dual realities of culture and economy as they are not just the interpreters of India’s art but are also valuable earners of foreign exchange. They evoke the myths, legends, and history of the people.

The traditional Indian saris have been abiding allies in feminine attire. The patchwork riot of intricately hand-woven coloured silk for winter, the shimmering brocades for a big wedding, and the pastel chiffons make for important occasions. It is a challenge today to use traditional skills, techniques, resources, and personal creativity and imagination without retarding the creative process involved. The shimmering threads twisted on a rickety frame of sticks and string, take months to emerge into a complete sari.

For at least two centuries Bengal’s handloom weavers produced the world’s amazing gossamer fabric, the fine muslins light as “woven air” that were in such great demand that Britain’s cloth manufacturers conspired to cut off the fingers of Bengali weavers and break their looms. The great tradition met its demise with the imposition of duties and a flood of cheap fabric from the new steam mills. Artistic knowledge, which had been passed down for possibly thousands of years teetered on extinction.

Mahatma Gandhi converted the dying art of spinning into a symbol of self-reliance and freedom. It was a new lease of life. One of the earliest acts of the government in India after the country attained freedom was to set up a national Board for the identification and development of crafts. It was natural that the ideal master-craftsmanship with its emphasis on quality and excellence should be reinstituted. In place of the warm patronage of dynastic rulers, and the sustenance provided by the guild, the new state regime had to step into the void.

Under colonial rule, which coincided with the Industrial Revolution in Europe, India was reduced to becoming a supplier of cotton to the textile mills of Manchester, Birmingham and Lancashire. The handloom weaver was virtually wiped out from the market as the country was forced to accept cloth of inferior quality manufactured in England. The palm-leaf painter, the gem cutter, the toymaker, the goldsmith, and myriad other artisans were squeezed out of the Indian marketplace.

The weavers’ craft is threatened with extinction by power looms which offer a cheaper and faster way to produce the same goods; it can take a weaver weeks to create what the machines can produce in a day. Moreover, machine products have a sophisticated finish. As a result, many weavers’ clusters in vast swathes of India are languishing. According to the 2019-20 National Census of Handloom Weavers, there are 31.44 lakh households engaged in weaving and allied activities, out of which 87 per cent are in rural areas. Competition from the power looms in the late 1950s further hastened the end to their already precarious livelihood. Realizing the predicament faced by the weavers in the post-independence period, the All India Handicrafts Board stepped in to provide a buffer to the weavers. In 1965, the Board instituted national awards to craftsmen. They were a public recognition of talent, skill, and above all, the creativity of these flag-bearers of a hoary tradition.

The reason for the present local co-operative being in bad shape is the poor working conditions. Poor wages have led to dwindling of the original strength of enrolled weavers. Only those unable to find work elsewhere continue to remain here. The guilds need to follow in the footsteps of Sholapur, where handloom weavers have kept abreast with newer innovative designs and diversification on an extensive scale.

Weavers have traditionally been organised into communities that have sustained their art and skill by preserving their traditional knowledge through oral traditions. Their craft is both an artistic tradition and a source of income and livelihood. The weavers and the workers who engage in this art are traditionally skilled and have been doing the same work for generations; it is a matter of culture and pride for them. One-fourth of the total cloth production in the country is from the handloom sector. In terms of employment, it ranks next to the agricultural industry. India is one of the few countries that have still a significant sector that employs artisans who weave for a living and produce almost 40 per cent of the cloth in the country. Handloom production is also eco-friendly, has a small carbon footprint, and is easy to install and operate. If it is revived and made lucrative, it would lead to a slowdown in rural migration. Also, 75 per cent of workers are women, and 47 per cent are from BPL families.

The artisan is not only a repository of a knowledge system that was sustainable but is also an active participant in its re-creation. To celebrate a craftsman’s perception of design, one must view our indigenous craft tradition which has evolved through an instinctive knowledge of the functional needs of a community.

A plan for the promotion of a craft can yield results only if it is a sincere exercise in which the craftsmen remain the key focus. However, more often than not, such efforts are generally short-term. They provide a mere band-aid, with critical issues airbrushed. Indian crafts have suffered primarily because of a lack of a visionary approach from the cultural administrators. An equally important issue is the preservation of the dignity of the craftsmen.

Traditional craftsmanship is losing value and the market offers poor compensation to the artisans for their skills and artistry. It’s a question of survival now, and many of these talented workers are continually scrambling for whatever work they can find, which is a huge loss of income and dignity for skilled artisans. The gap between skill training and employment has widened, leading to a situation where the youth are unable to find the employment that they are aspiring for and employers are unable to find workers who are appropriately trained for the job.

The earning ability of the weavers can be enhanced by putting them directly in contact with markets. Weavers should be empowered to become micro-entrepreneurs enabling them to combine their traditional skills with modern concepts. The training programmes for weavers should not be one-size-fits-all; some weavers are more creative and more interested in designing, some in entrepreneurship, and some in marketing. Trainers should be cognizant of the specific needs of the weavers to build on their core strength.

We need to adopt the ecosystem approach, building the core strength of different classes and clusters of weavers while reviving and reinterpreting the traditional designs to respond to the emerging tastes and choices of wider markets. Traditional skills can still be a viable means of livelihood if we can use new design concepts and diversify product range to cater to a much broader clientele. This will require innovations that can be facilitated through handloom boards of the government.

The migration of traditional craftsmen to other vocations would only mean the end of a venerated tradition that was an integral part of our rich civilization. Craftsmanship is an heirloom that is passed from one generation to the next; it cannot be reinvented. A women craftsman, a moulder of icons, was once asked from whom she learned her knowledge. She replied, “from time as the most ancient, the parampara. We are the holders of sight and skill. We carry it in our wombs”.