Towards the end of the eighteenth century and beginning of the nineteenth, the situation started to change for the better in India. In generating this new awareness, which is often termed as the beginning of the nineteenth century Indian Renaissance, the establishment of the Asiatic Society in Bengal (1784) was an important milestone.

A group of English scholars, the most important of whom was Sir William Jones (1746-94), enthusiastically started to dissect the ancient Sanskrit literature and out of this serious research, the twenty volumes of Asiatic Researches emerged providing a lot of interesting and stimulating facts of Oriental and Indian civilizations. These were unknown even to the then educated Indians. The second important factor in the awareness was the introduction of Western education.

Advertisement

This was achieved by the joint collaboration of enlightened Indians and Christian missionaries bringing Indians in contact with the West and Western thought. Bacon, Locke, Voltaire, Burke, Bentham, James Mill and Newton became familiar names. The third impact was that of the French Revolution of 1789 especially in the minds of the Indian youth. In this context, one example might help us in assessing the magnitude of this influence.

The Christian missionary, Alexander Duff recorded that in just one ship, one thousand copies of Paine’s Age of Reason arrived. At the beginning, the book was sold at just one rupee but because of the tremendous demand its price increased manifold within a few days. Within a short time, a cheaper edition of all works of Paine was published. The net impact of all these developments changed dramatically the intellectual climate of India in general and Bengal in particular within a few decades.

In this period of ferment three different schools of thought emerged. The first was influenced by the Western rationalistic outlook and was iconoclastic. It was critical of both authority and tradition and wanted total abolition of the caste restrictions and practices. Though most of them were young and did not adopt Christianity, they “renounced the whole system of Hinduism” and as noted by O Malley, “there was little sympathy either between them and their countrymen or between them and the English, they had been raised out of one society without having a recognized place in another”.

The leader of this radical movement was Henri Derozio (1809-31). The second group consisted of conservative Hindus who wanted to uphold social and religious status quo. It was led by well-to-do Hindus. Though they were spokesmen for Hindu conservatism, they were practical minded people and championed the cause of English education, as they were shrewd enough to realize that such knowledge would be beneficial to them.

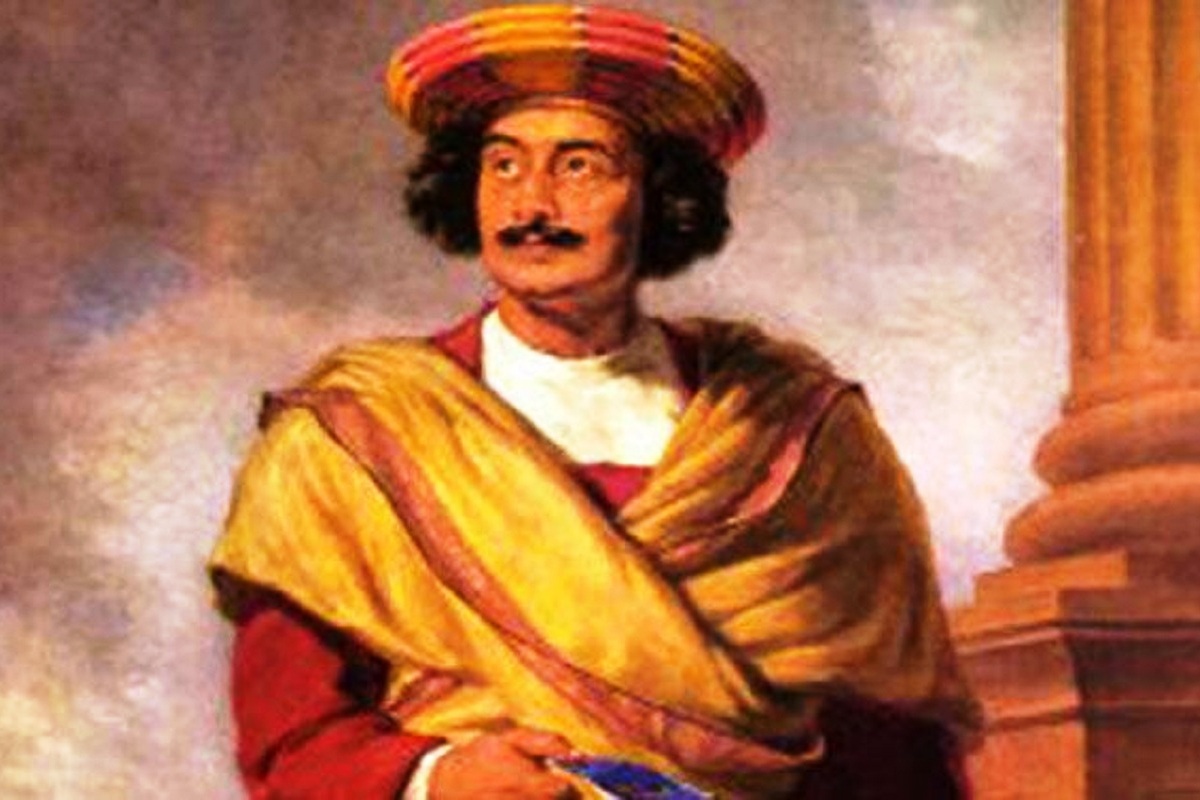

But though they wanted to learn English as a language they showed little inclination to assimilate Western thought and culture. What helped them most was the policy of the East India Company of non-interference in regard to Indian religious rites and social practices. The most well-known of them was Radhakanta Deb (1784-1867). The third school of thought was typified and identified with Raja Rammohun Roy (1772- 1833).

Rammohun attempted to reform society and religion from within by incorporating the positive aspects of Western thought and culture. His role was like that of Martin Luther (1483-1546)’s in the European context. Just as Luther appealed to the Bible as the authority against medieval degeneration and corruption, similarly Rammohun took his stand on the basis of the Vedas, the oldest Hindu scriptures in which he discovered a form of pure and undiluted Hinduism.

But there was, unlike Luther, another side of Rammohun, namely his cosmopolitanism as he assimilated what was good and useful in other civilizations, cultures and religions. For instance, he was attracted to monotheism by his contact with the Muslims. He was also deeply influenced by the ethical teachings of Christianity and believed that asceticism was not essential for leading a religious life, as it could be fulfilled within social surroundings.

Subhash Chandra Bose correctly pointed out that Rammohun was the first to assimilate with Indian culture, Western scientific culture. “The Indian Renaissance”, according to Susovan Sarkar “was possible only because a principle was discovered by which India could throw herself into the full current of modern civilization in the outer world without totally discarding her past”. Rammohun became the most representative example of this Renaissance in its formative period.

It was because of such a remarkable achievement, that all the important thoughts and movements of the nineteenth century, social, religious and political in India, according to RC Majumdar, began with Rammohun. What Hegel was to Western thought, Rammohun was to Indian political thought. Rammohun’s early life was spent learning Hindu and Islamic thought. In more mature years, from the age of twentytwo, he came in contact with an Englishman, Digby and mastered English and became immensely interested in Western ideas.

This exposure was of crucial significance in Rammohun’s intellectual development as this enabled him to come in contact with some very important European thinkers and awareness of historic developments like the American War of Independence and the French Revolution. Rammohun was a prolific writer and his works are estimated to be about eighty and out of these, eight dealt with different aspects of political philosophy. His method was inductive and with his concern for the primacy of social reform his ideas were spread all over his writings including letters.

In the evolution of his political ideas, the most important influences were those of Bentham and Montesquieu. From Bentham he picked up the rejection of natural law theory and the distinction between law and morals. The influence of Utilitarianism was also discernible but whereas Bentham was more rigid and believed that the same principles could operate throughout the world, Rammohun accepted wide variety and plurality. From Montesquieu, he borrowed the theory of separation of power and the idea of the importance of the rule of law.

Rammohun, like Montesquieu, accepted the ultimate sovereignty of the people which was one of the important reasons for his support for direct British parliamentary legislations in colonial India. Rammohun disagreed with the most important idea of the ancient Indian legal system, namely that the basic or the fundamental law was of divine creation and that all other laws emerged from this basic law. For him, law was the command of the sovereign and as such, reformist law emerged from the sovereign authority. He was conscious of the impact of public opinion and emphasized the need for freedom of expression.

But he equally stressed the importance of the superior authority for declaring law as command. In the context of India, he asserted that Hindu society was incapable of reforming itself from within. The remedy as such was to make the British Parliament responsible for enacting laws for India. This was defended on two grounds: (1) that Western law emerged from a sovereign authority and (2) because of the separation of legislative and executive responsibilities.

Proper legislation could provide the basis of a rule of law. In contrast to this in India, all the powers were vested in the executive, which was not conducive for wholesome and progressive legislation. He also thought, like Burke, that the British Parliament was not influenced by small petty interests. Unlike the executive authorities in India, the British Parliament would be more interested in the permanent rather than the immediate interests. The situation in India in the early nineteenth century vindicated this stand, as the local administration as well as the Indian intelligentsia was reluctant to take any risk.

Even the historic decision of Lord William Bentick (1774-1839) to ban sati in 1829 did not have the approval of all the sections of educated Indians. Moreover, during the first eighty years of English rule, only two positive social legislations emerged: (a) Regulation of 1829 banning sati and the (b) Hindu Marriage Act of 1855 passed at the instance of another great social reformer, Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar.

(To be concluded)

(The writer is a retired Professor of Political Science, University of Delhi)