Popcorn: The high-fibre, low-calorie snack your body will love!

Discover why popcorn is a healthy snack: high in fibre, low in calories, and great for digestion, blood sugar control, and weight management. Enjoy it guilt-free!

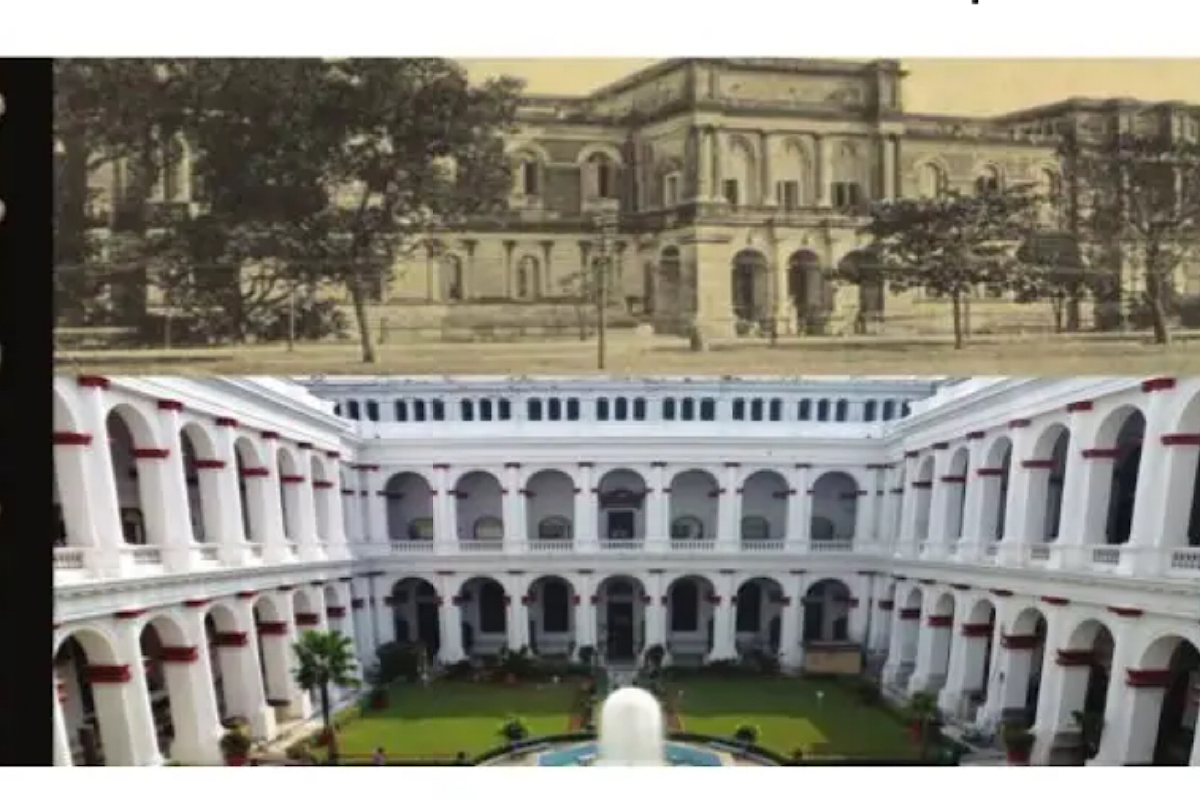

On 18 May, International Museum Day, it is only befitting to pay homage to several generations of men like Sir Asutosh who lived to preserve heritage, while making history themselves during their lifetimes.

RAJU MANSUKHANI | New Delhi | May 18, 2024 8:03 am

Representation image

On 28 November 1913, Justice Sir Asutosh Mookerjee, Chairman of the Trustees of the Indian Museum in Calcutta, delivered the inaugural address marking the first centenary of the Museum. His address forms the first chapter of ‘Indian Museum 1814-1914’, a commemorative volume published for an institution which is a landmark among museums of India.

On 18 May, International Museum Day, it is only befitting to pay homage to several generations of men like Sir Asutosh who lived to preserve heritage, while making history themselves during their lifetimes. “To appreciate the history of the origin and growth of the Indian Museum,” explained Sir Asutosh, “we must travel back to the last quarter of the eighteenth century when, after the establishment of British supremacy in this Province, Sir William Jones, one of the profoundest scholars, who have devoted their life to the service of India, founded the Asiatic Society in 1784, and with the boldness which characterized his genius, stated that the bounds of its investigations would be the geographical limits of Asia, and that within these limits, its enquiries would be extended to whatever is performed by Man or produced by Nature.”

Advertisement

By 1808, the Asiatic Society was looking for permanent premises for its accumulations were growing. Land was granted by the Governor at the corner of Park Street. Sir Asutosh brings alive the fascinating Dr Henry Wallich, a Danish botanist taken prisoner at the siege of Serampur but released in recognition of his scientific attainments. In 1814, Dr Wallich wrote to the Asiatic Society advocating the formation of a museum and “offered not only to act as a Honorary Curator but also to supply duplicates from his own valuable collection to form a nucleus.

Advertisement

The proposal found ready acceptance with the Society and it was determined to establish a Museum to be divided into two sections: one which would now be called archaeological, ethnological and technical, and the other geological and zoological.” Dr Wallich inspired collectors like Col. Stuart, Dr Tytler, General Mackenzie, Brian Hodgson, Capt. Dillon and Babu Ramkamal Sen who readily placed at the disposal of the Society interesting and curious objects collected from various parts of the country.

In 1836, there were a host of financial problems and the Society wrote to the Government for funds. Sir Edward Ryan, president of the Society, and the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court took the lead in galvanizing support for the Museum, its maintenance and salaries for the Curators and Keepers. What transpired in their correspondence remains relevant and true till date. “A Museum could not be established by voluntary subscriptions nor maintained in the creditable and useful condition necessary for the attainment of the object desired, unless aided liberally by the Government, in like manner as similar institutions in Europe were supported from the public treasury.”

Dr J.T Pearson, Dr McClelland, Edward Blyth: the roll call of names continues through the 19th century as the Asiatic Society grew with collections that also reflected the needs of colonial times. A Museum of Economic Geology was founded and large valuable collections of specimens were deposited from 1840 onwards. It is a paradox of the colonial State that while it was ruthlessly subjugating, exploiting the provinces through trade, commerce, and brutal wars, it was also empowering these men of great learning and dedication to establish institutions. Long before the 1857 Mutiny and India’s first war of independence, the Society was appealing for the establishment of an Imperial Museum; it took almost a decade, by 1866 the Indian Museum Act was promulgated.

“The valuable collections of the Society, accumulated during half a century by a long succession of enthusiastic members were formally transferred to a Board of Trustees of which Sir Barnes Peacock, then Chief Justice of Bengal, was appointed President,” said Sir Asutosh in his address. It was by 1875 that the Museum ceased to be the property of Asiatic Society of Bengal and was transformed into an Imperial Institution and the Museum building became one of the largest in the city. Through the 1880s and early 1900s the Museum was led by Dr John Anderson, Mr James Wood-Mason, Sir Thomas Holland, Mr Thurston, Dr Watt and Sir Herbert Risley. New galleries were opened and the Museum was divided into zoological and ethnological, geological, art, industrial and archaeology.

The archaeological collection soon occupied centre stage with General Alexander Cunningham gaining pre-eminence, leaving his mark on 20th century developments. “To him we owe the removal and preservation of the Bharut Stupa Rail, now one of the finest and most interesting existing relics of early Indian architecture,” said Sir Asutosh paying his homage. The extensive invaluable collection of coins lent by the Asiatic Society, catalogues produced by Mr CJ Rodgers, Mr Vincent Smith and Mr Nelson Wright were acknowledged. Raja Sir Sourindra Mohun Tagore’s collection of Indian musical instruments was presented to the Museum.

Going ahead Sir Asutosh underlined a significant achievement, “namely, the distinguished part taken by the Indian Museum in the noble cause of the advancement of knowledge. It would be difficult to overestimate the importance of the biological and geological research strenuously carried out by our officers, though it was by no means easy to assign, except in the case of zoology, the precise share of credit for such work to the Indian Museum as distinct from the related scientific departments of Government.

It may be maintained, without risk of contradiction that all the research work not only in zoology and geology but also in meteorology and archaeology, now undertaken by different Government Departments owes its origin in activities of the Asiatic Society of Bengal. The study and investigation of Applied Science, more particularly, Botany and Chemistry, also had a similar origin.” In Sir Asutosh’s address what comes alive is how a century ago a small band of scholars, engaged in the study of the history, languages and antiquities laid the foundation for a Museum in Calcutta, entirely with limited private means at their disposal; how it took the ruling authorities thirty years to realize their responsibilities in this direction. Has the Indian Museum fulfilled its mission? Sir Asutosh searched for answers, “It is now generally recognised that a museum is an institution for the preservation of those objects which best illustrate the phenomena of Nature and the works of Man, for the utilization of these in the increase of knowledge, and for the culture and enlightenment of the people.

A National or Imperial Museum must, consequently, be equipped adequately for the fulfillment of three principal functions: first, for the accumulation and preservation of specimens such as form the material basis of knowledge in the Arts and Sciences; secondly for the elucidation and investigation of the specimens so collected and for the diffusion of knowledge required thereby; and third, to make suitable arrangements calculated to arouse the interest of the public and to promote their instruction.” With a degree of satisfaction, he stated, “As regards the first two of these functions, the Indian Museum has no reason to reproach itself. But I regret to confess, with a feeling of disappointment, that when I examine the history of Indian Museum from the point of view of its third function as a possible powerful instrument for the instruction of the public, I cannot say that the fullest measure of success has been achieved.

The Museum may be regarded, first, as an adjunct to the class room and the lecture room; secondly as a bureau of information; and thirdly as an institution for the culture of the people.” Sir Asutosh’s speech, a clarion call for all generations, noted, “If we desire to furnish to the advanced or professional student, materials, and opportunity for laboratory training; if we desire to aid the teacher of elementary, secondary or technological knowledge in expounding to his pupils the principles of Art, Nature and History; our scientific staff must be materially strengthened…through the display of attractive exhibition-series, wellplanned, complete and accurately labelled and thus to stimulate and broaden the minds of those who are not engaged in scholarly research. I desire consequently to emphasize the urgent need for the improvement of our public galleries.” Sir Asutosh’s words of timeless wisdom are an appropriate occasion to also commemorate the centenary, on 25 May, of the passing away of this educationist-jurist extraordinaire.

(The writer is a writerresearcher on history and heritage issues, and a former deputy curator of Pradhanmantri Sangrahalay)

Advertisement

Discover why popcorn is a healthy snack: high in fibre, low in calories, and great for digestion, blood sugar control, and weight management. Enjoy it guilt-free!

The sparrow's disappearance signals an environmental crisis. Learn simple steps to protect and bring back this beloved bird to our homes.

India has banned 16 Pakistani YouTube channels for spreading provocative and communally sensitive content, along with false and misleading narratives targeting India, its Army, and security agencies.

Advertisement