Preity Zinta slams Congress party for spreading false news about her

She refuted INC Kerala's claim that she handed over her social media to BJP and had a loan written off, calling it "fake news." Details inside.

ver the century, there was the bigger goal of ‘freedom and independence’ for which a spectrum of political parties, groups and individuals were campaigning in the legislatures, writing vociferously in the media, pleading openly to the imperial powers-that-be, and taking to the courts, and streets, unafraid of being in jails. These were journeys where intentions and imagination, ideals and action went hand in hand

Raju Mansukhani | March 1, 2023 8:41 am

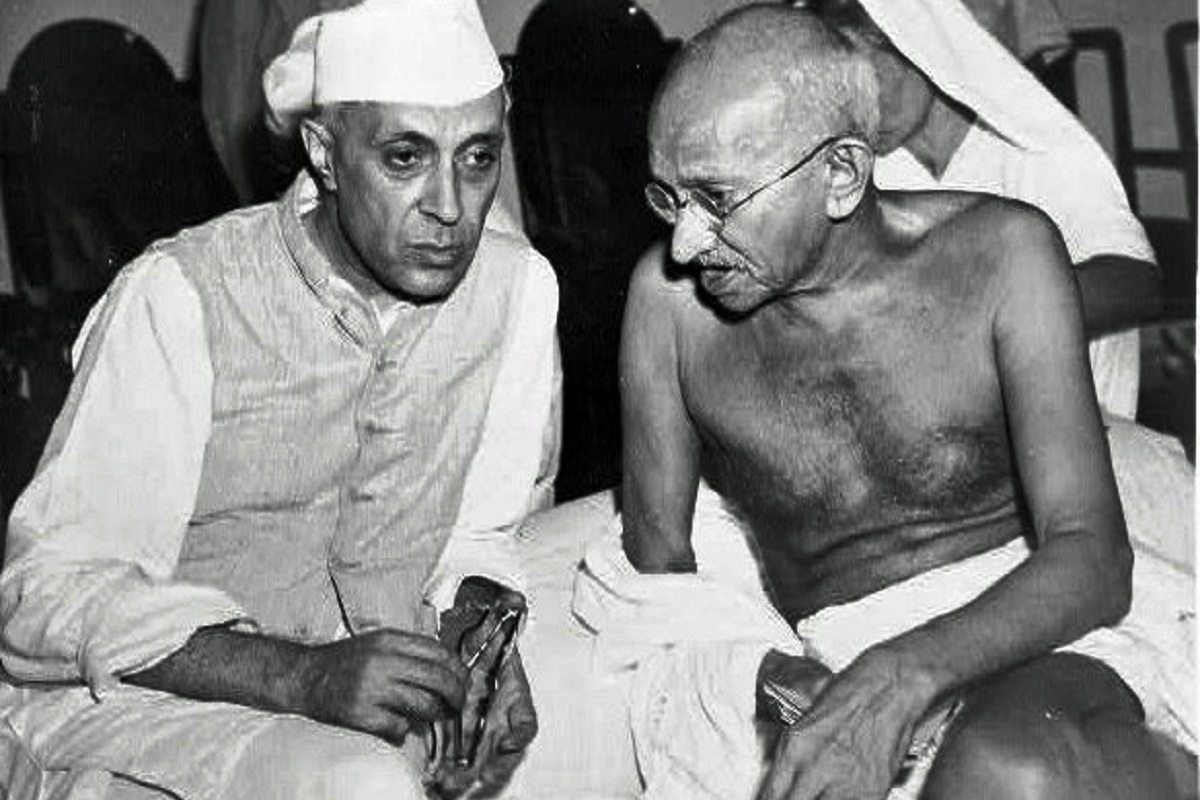

Jawaharlal Nehru with Mahatma Gandhi (Image: Facebook/@Jawaharlal-Nehru)

It is being billed thus: ‘137 Year Journey of Ideas Continues’. A full-page advertisement of the 85th plenary session of the Indian National Congress from 24 to 26 February brought readers, once again, face to face with the venerable pantheon of India freedom-fighters.

Placed in two rows were photographs of Mahatma Gandhi, Pt Jawaharlal Nehru, Sardar Patel, Dr BR Ambedkar, Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose, Sarojini Naidu, Lal Bahadur Shastri, Indira Gandhi, Rajiv Gandhi, and PV Narasimha Rao.

Advertisement

Not just the imagery of the advertisement, or the choice of iconic leaders where Sarojini Naidu shared space with Rajiv Gandhi, what seemed incongruous was the headline: ‘137 Year Journey of Ideas’.

Advertisement

The Congress party, its leaders national and regional, and the tumultuous decades of freedom struggle may not be so easily summed up as a ‘Journey of Ideas’, however long that journey may have been. ‘Ideas’ seemed a trifle trivial, almost without capturing the power and substance of our freedom struggle. Nor does it comprehensively do justice to the role of the Congress for 137 years.

While the metaphor of journey is certainly tangible, and associated with movement and dynamism, the word ‘ideas’ is far too intangible to bring any recall or strike a chord with readers, especially the millennial generations.

In today’s day and age, readers may relate more vividly and strongly to these Congress leaders for their dedication towards nation-building, building community linkages, and most importantly, building the character of individuals.

If there was a journey, it was a journey of nation-building and character-building which brought MK Gandhi to the shores of India in 1915, and made Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose leave the shores of his Motherland in 1941, often hailed as The Great Escape.

Over the century, there was the bigger goal of ‘freedom and independence’ for which a spectrum of political parties, groups and individuals were campaigning in the legislatures, writing vociferously in the media, pleading openly to the imperial powers-that-be, and taking to the courts and streets, unafraid of being in jails.

These were journeys where intentions and imagination, ideals and action went hand in hand. It was on 18 March 1922 that the historical trial of Mahatma Gandhi and Shankarlal Banker, editor-printer-publisher of Young India, was held in the district and sessions court of Ahmedabad. They were being charged under Section 124 A of the Indian Penal Code. Gandhiji read his statement in court and it merits constant revisiting.

“I owe it perhaps to the Indian public and to the public in England, to placate which this prosecution is mainly taken up, that I should explain why from a staunch loyalist and co-operator, I have become an uncompromising disaffectionist and non-cooperator. To the court too I should say why I plead guilty to the charge of promoting disaffection towards the Government established by law in India. My public life began in 1893 in South Africa in troubled weather. My first contact with British authority in that country was not of a happy character. I discovered that as a man and an Indian, I had no rights. More correctly I discovered that I had no rights as a man because I was an Indian. But I was not baffled. I thought that this treatment of Indians was an excrescence upon a system that was intrinsically and mainly good. I gave the Government my voluntary and hearty cooperation, criticizing it freely where I felt it was faulty but never wishing its destruction,” he said.

Gandhiji in court raised the issue of ‘real freedom’ when he referred to the recently-passed Rowlatt Act. “The first shock came in the shape of the Rowlatt Act ~ a law designed to rob the people of all real freedom. I felt called upon to lead an intensive agitation against it. Then followed the Punjab horrors beginning with the massacre at Jallianwala Bagh and culminating in crawling orders, public flogging and other indescribable humiliations. I discovered too that the plighted word of the Prime Minister to the Mussalmans of India regarding the integrity of Turkey and the holy places of Islam was not likely to be fulfilled. But inspite of the forebodings and the grave warnings of friends, at the Amritsar Congress in 1919, I fought for cooperation and working of the Montagu-Chelmsford reforms, hoping that the Prime Minister would redeem his promise to the Indian Mussalmans, that the Punjab wound would be healed, and that the reforms, inadequate and unsatisfactory though they were, marked a new era of hope in the life of India.”

His compassion, entwined in historical fact and barbarity of the British Raj, remains a beacon of light in our political history. Gandhiji’s statement highlighted the drain of wealth from India, speaking up for the political and economic ‘helplessness’ of its people and need to resist the powerful imperial government.

Through the words of Emily Kinnaird, an ardent missionary who spent over four decades in India, we find the ‘love for the idea of India which is the concern of the Indian intelligentsia’. What Kinnaird wrote about was ‘one of the most incalculable forces in the country’, quite so for the imperial rulers.

It was the late 1920s and the ferment within the Congress Party, the Communists and labour unions was reflected in the atmosphere of defiance and rebellion. When Pt Jawaharlal Nehru made the Purna Swaraj speech in 1929 as President of the Congress Party, it dramatically changed the political narrative. Pt. Nehru pointed out that though the country’s social structure had proved to be wonderfully stable, it had failed in one vital particular: it had found no solution for the problem of equality. He went on to say that Indian society was based on inequality but it had the genius to find a solution and the discords between the various communities were to disappear.

He said, “… by right of birth I shall venture to submit to the leaders of the Hindus that it should be their privilege to take the lead in generosity. That was not only good morals but often good politics and sound expediency… The time was coming soon when such labels as Hindus, Muslims and Sikhs would have little meaning and when struggles would be on an economic basis.”

The resolution was short and focussed on the disastrous impact of the British rule in India. “We hold it to be a crime against man and God to submit any longer to a rule …. We recognize, however, that the most effective way of gaining our freedom is not through violence. We will therefore prepare ourselves by withdrawing, so far as we can, all voluntary association from the British Government, and will prepare for civil disobedience, including non-payment of taxes. We are convinced that if we can but withdraw our voluntary help and stop payment of taxes without doing violence, even under provocation, the end of this inhuman rule is assured. We therefore hereby solemnly resolve to carry out the Congress instructions issued from time to time for the purpose of establishing Purna Swaraj,” it read.

Around the same time, in 1928 at a provincial conference in Poona, it was Subhas Chandra Bose who delivered a speech which may fill in the gaps for the Congress Party in 2023.

He said, “Indian nationalism is neither narrow, nor selfish, nor aggressive. It is inspired by the highest ideals of the human race viz., Satyam (the true), Shivam (the good), Sundaram (the beautiful). Nationalism in India has instilled into us truthfulness, honesty, manliness and the spirit of service and sacrifice. What is more, it has roused the creative faculties which for centuries had been lying dormant in our people and, as a result, we are experiencing a renaissance in the domain of Indian art.”

Bose invariably shared an internationalist perspective in his speeches. He said, “Another attack is being made on nationalism from the point of view of international labour or international Communism. This attack is not only ill-advised but unconsciously serves the interests of our alien rulers. It would be clear to the man in the street that before we can endeavour to reconstruct lndian society on a new basis, whether socialistic or otherwise, we should first secure the right to shape our own destiny. As long as India lies prostrate at the feet of Britain, that right will be denied us. It is, therefore, the paramount duty not only of nationalists but anti-nationalistic Communists to bring about the political emancipation of India as early as possible.”

Equality. Brotherhood. Justice. Service. Sacrifice. Agitation. Non-Cooperation: be it Mahatma Gandhi, Pt Jawaharlal Nehru or Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose, they lived, worked, died for these universal ideals which became intrinsic to our freedom struggle. We, not just the Congress today, could embark on such a Journey of Ideals to build, rebuild, and develop our nation, our communities and our citizens.

(The writer is a researcherwriter on history and heritage issues, and former deputy curator of Pradhanmantri Sanghralaya)

Advertisement

She refuted INC Kerala's claim that she handed over her social media to BJP and had a loan written off, calling it "fake news." Details inside.

Jesus Jimenez, Korou Singh, and Kwame Peprah scored a goal each as Kerala Blasters FC defeated Chennaiyin FC 3-1 in a key clash of the Indian Super League (ISL) 2024-25 season at the Jawaharlal Nehru Stadium here on Thursday night.

Congress President Mallikarjun Kharge on Saturday paid heartfelt tributes to India's second Prime Minister, Lal Bahadur Shastri, on his 59th death anniversary, remembering his remarkable contributions to the nation.

Advertisement