Social media is agog discussing the proposed demolition of the annexe building of the National Archives, a magnificent building in New Delhi. This annexe building had seen a number of renovations and alterations four years ago, the cost of which would certainly have been a dear sum.

On 20 May 2021, Mr Tassadaque Hussain, retired Deputy Director of NAI wrote on his Facebook wall, “I feel terrified at the very thought of this, relatively new (of 1980s), functional 6-storey building, being pulled down for the proposed Central Vista Project. This houses some of the priceless documentary heritage of the country. Any dislocation will come with a huge price……Please, please save this building!!”.

Advertisement

I was a frequent researcher at the archives for nearly half a decade. I witnessed first-hand, the mishandling and defacing of documents that took place every single day, by the staff and researchers alike. While the world is crying hoarse about the demolition of the heritage structure, what happens inside this repository is truly horrifying.

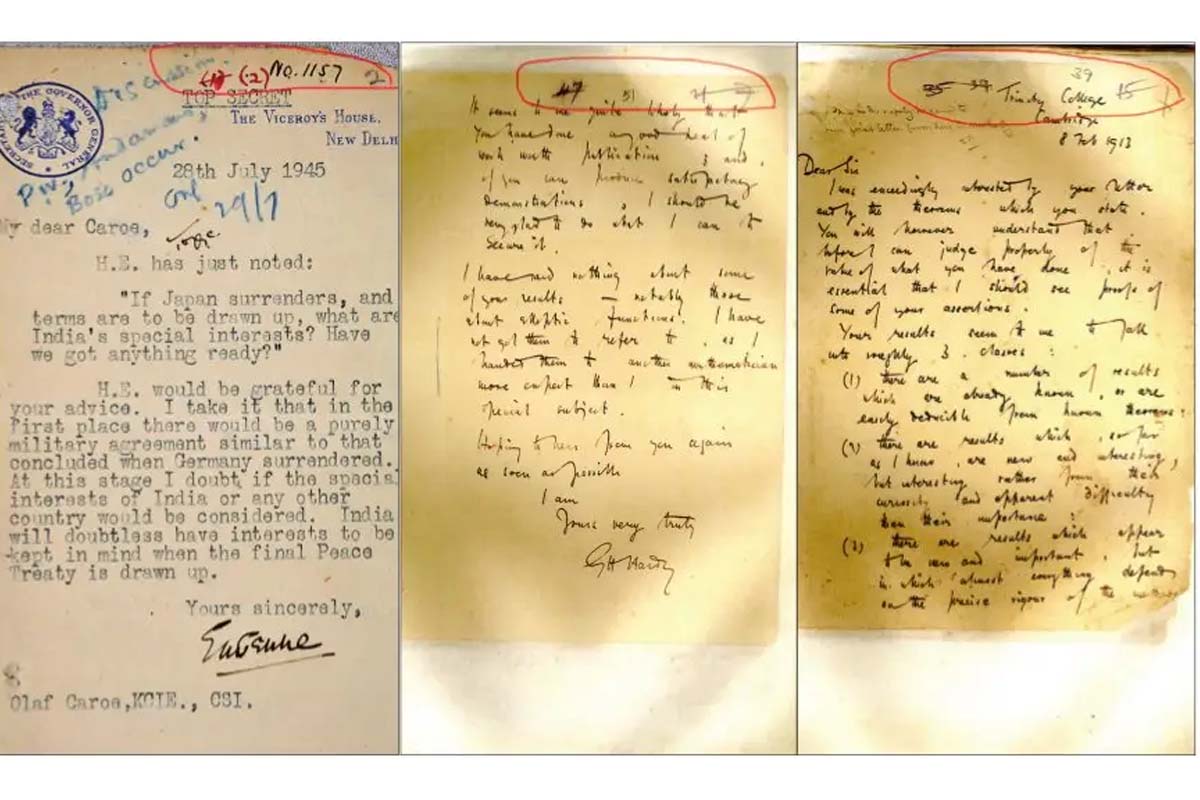

Thanks to callous mishandling, priceless documents are dog-eared and annotated. Staff at the research room mandate scholars to number all the pages of a document selected for photocopying. As a result, documents end up with multiple page numbers, at times made with a pen right in the middle of a document. Some scholars highlight portions important to them using coloured pens – on original documents!

Section 11 (8) of the Public Records Rules, 1997 prohibits anyone from writing on public records, and from carrying any eatables inside the research room. During photocopying and scanning, delicate archival pages are disengaged from the file, handled sloppily, thrown on the floor only to be put back in a haphazard manner. Professionals engaged in digitizing documents were seen keeping their tea cups on the documents. I found a staffer brazenly eating an orange right over the documents on her table. A 1947 document on Travancore has some completely tattered pages whose pieces are bunched together and tucked inside the file.

If Buckingham Palace can be infested with rats, why should not the National Archives too. Cats and rats have a field day in the repository. If you receive a file that stinks to high heavens, you know it comes with blessings.

The condition of the fragile pages of history, tattered edges with layers of dust accumulated on them, is appalling. To me, it seemed that the officers were more bothered about their personal growth; publishing books and foreign jaunts.

“It’s the first time I’m hearing about this, it’s shocking, this is blasphemous,” said Dr. Sanjay Garg, Deputy Director, NAI, when I brought this to his notice.

I interacted several times with Tassadaque Hussain, then Deputy Director, in connection with receiving smudged photocopies of documents, over hundreds of pages. I apprised him of the mishandling of documents, poor condition of the research room and facilities. My attempts to seek answers and rectification fell on deaf ears. Post retirement these officials seem to develop great value for the treasures housed inside.

Many sheets of a file containing documents and original letters pertaining to mathematical genius Ramanujan are missing. Perhaps these were mathematical equations. It is visible that they have been torn away. Who tore them away, were they stolen or sold? These questions will most likely remain unanswered.

In his book ‘White Mughals’, William Dalrymple writes about the destruction of records owing to the callousness of NAI staff. “Someone installing a new air conditioning system had absent mindedly left out in the open all six hundred volumes of the Hyderabad residency Records. It was monsoon. By the time I came back for a second look at the records the following year, most were irretrievably wrecked, and those that were not waterlogged were covered with thick green mould”.

Accessing files is an intimidating experience. Most file requisitions come back marked ‘NT’ (not transferred from the ministry). How then are these files indexed with a complete tracking number? There is no process in place to help scholars find files, which require navigating through a labyrinthine file index. Precious time is lost, especially for researchers from outside New Delhi.

Students fear vindictiveness and hesitate to complain, as do many academicians and scholars since they feel they have to revisit the archives for their work. If you want to have smooth access to the files you either have to be a VIP, or relative of the officers at NAI.

A minor son of an officer, studying in class seven was utilising the staff and resources of the archives to complete his school project. The archivist on duty was busy fetching documents for this boy and taking photocopies, while the boy happily wandered around the research room the entire day.

The National Archives houses documents dating back to 1748, a rich collection of private papers, over 7,500 microfilm rolls, and records from several countries. Scholars, academicians, authors, journalists and students frequent the repository; works by renowned authors and researchers have emanated from this goldmine.

If this is the state in which documents are ‘preserved’ one shudders to think of what would happen when the documents are being shifted to their new ‘abode’. More than buildings and structures, it’s the rot inside that causes a greater stench. What is at stake is the documented history of our country.

The writer is an independent journalist.