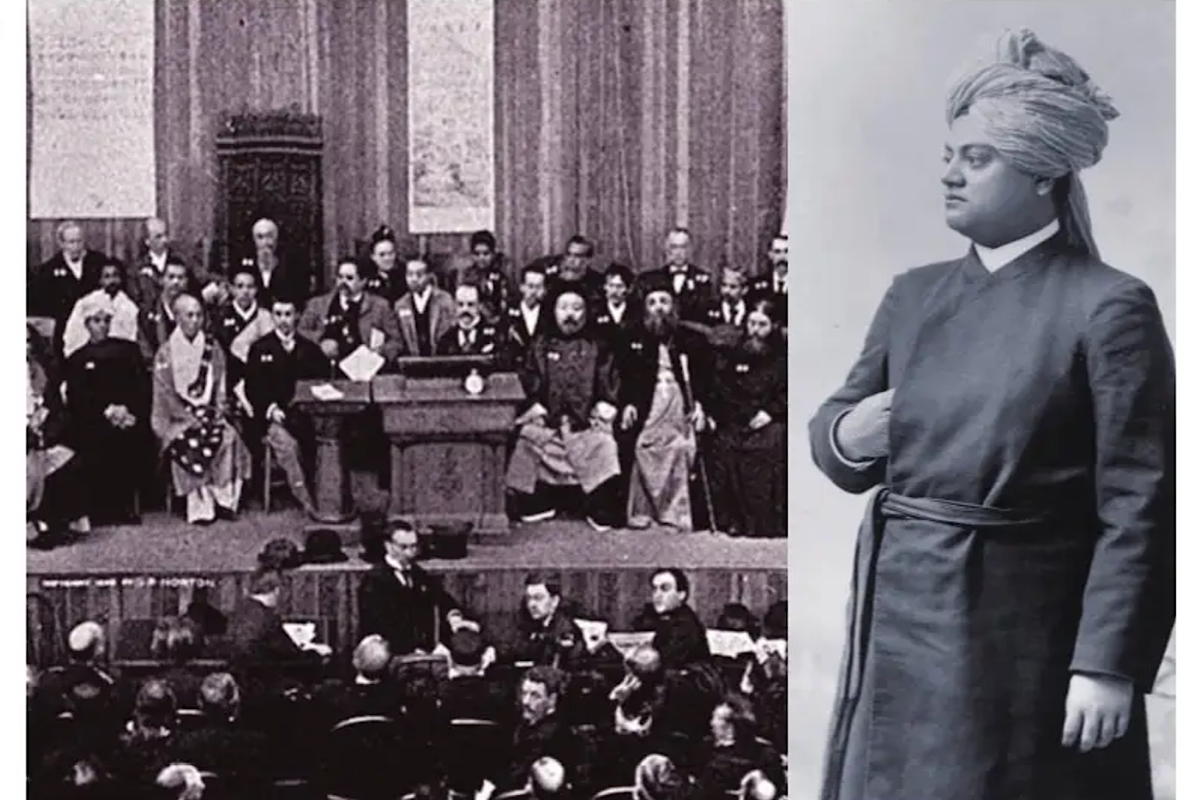

It was September of 1893 when a charismatic young man named Narendranath Datta aka Swami Vivekananda took the podium at the Parliament of Religions held in Chicago and brought the hall down with his opening address: “Sisters and brothers of America”. He introduced the key message of Hinduism that all religions lead to the same God, not only to the Americans but to an international audience. He went on to become one of the most influential figures of modern India.

Now 130 years later and, in a city (Milwaukee), about 90 miles from Chicago a charismatic Vivek Ramaswami (VR) once again drew the attention of Americans to Hinduism; he did not say anything about his religion but was described as the first Hindu Indian candidate in a US presidential election. An American friend asked me right after the first GOP primary debate to explain to him the essence of Hinduism and how it differs from Christianity. I was honest with my answer. “See, I am not a practicing Hindu and cannot explain my religion to you in a few sentences or even a few paragraphs. My appreciation for Hinduism came from reading only one chapter of one book – chapter 43 of An Autobiography of a Yogi by Yogananda. It is available on the internet for free; perhaps you can read it first and then we can have a discussion”. I have thought about my friend’s question many times since then and realized that there are many reasons why Hinduism is such a complex subject.

Advertisement

Is it a religion or a set of religious beliefs, a spiritual or philosophical discourse, a mythology or just a way of life? There are so many different denominations, so many different teachings and so many deities: Krishna, Shiva, Kali, Ganesha, Brahma, Hanuman and so on. There is no central prophet like Jesus, Buddha or Mohammad. The scriptures are written in Sanskrit which makes them impossible to read for most people. Even their translations in local languages or popular speeches given by swamis dwell on lengthy interpretations of various difficult Sanskrit words and slokas.

Instead of asking “what is Hinduism?”, I ask myself “why do I even need to follow a religion?” In my opinion, any religion or spiritual guidance must answer three basic questions: a) Is there a God and if so, how does He manifest himself? b) What happens after death and most importantly, c) is there a guideline on how to properly live our lives and what happens if we do not follow them? Hinduism was not attractive to me during most of my early life. I called myself Hindu because my parents were Hindu. Our religion tends to personify God; all the deities and rituals evolve around these personifications. Such personifications exist in other religions too but not to the same extent. One wonders which deity to follow as one’s God and why. I heard about the concept of reincarnation from my childhood.

It seemed like a more reasonable alternative to the concept of “one life to live” and then go to heaven or hell. However, I always had many unanswered questions about reincarnation. The guideline for living a proper life gets too complicated, if not confusing and once again because there are so many different variations. In Christianity, the directions are simple: the ten commandments and other Biblical instructions. The list is also straightforward in other religions and seems to agree with our common sense. Hindu directives get too elaborate and too vague for me.

I read Paramhansa Yogananda’s book “An Autobiography of a Yogi” later in life and finally discovered my roots in Hinduism. In chapter 43, titled “Resurrection of Sri Yukteswar”, Yogananda is not preaching Hinduism nor trying to interpret slokas from scriptures; he even did not use the word “Hinduism”. He is simply narrating like a reporter what his guru, Sri Yukteswar told him about Yukteswar’s personal experience after death in plain language; it was as if Yukteswar was describing a travel experience to some new country.

There is nothing like this in the entire literary collection on religion and spirituality. Most importantly, Yukteswar’s narrative answered my three questions. Since I am a physicist by education, I will try to explain my understanding using a physical “model” – using the word “model” loosely. The continuum of existence of every person can be modelled as a ball or a sphere with three layers or shells: the outermost shell is the physical layer followed by an emotional layer and finally a layer of wisdom. Inside the layers lies an indescribable entity; call it energy or spirit or God. Each reincarnation is equivalent to bouncing of the ball from a rigid reflecting surface.

Reflection is necessary for introspection. Impact from this surface tears up the layer a little bit and upon hundreds of bouncing the entire physical layer comes off. At this point we have lost all our physical senses, but the second layer is still there. We can still feel emotions and communicate through “extra-sensory perception”. The second layer also eventually disappears, and we are then reborn as pure wisdom. There is no physical body, no emotion – just intellect. We can only think and meditate.

Once the third layer is also gone, there is nothing left to hold the spirit inside the sphere, and it flies off into the vast never-ending space of universal consciousness. This is Nirvana. We unite with God and there is no further reincarnation. This is the end. As a physicist, this picture is much more appealing to me, compared to endless cycles of reincarnations or a heaven-hell status-quo. So, how should we live our dayto-day life?

The simple answer is “it does not matter” because life is just an illusion and does not mean anything. However, everyone will probably agree that life on this earth is miserable, and no one wants to experience it over and over again.

So, the goal should be not to come back to this world again. All the disciplines in Hindu religion, advocated by Vivekananda, Yogananda and many others, prescribe repeated practice of meditation that makes one realize the futility of life and seek a different world. It also does not matter if one does not follow any such discipline or religion; one will reach this realization sooner or later in one’s own way, if not in this life, certainly in one of hundreds of lives to follow. Even a sinner gets tired of his sins and a killer finds God in prison.

The real benefit of a religious discipline is that it allows one to take a short-cut to minimize the number of incarnations and get to Nirvana faster. This is why Hinduism does not have a set of commands; it does not say “thou shall do” this or that. Also, Hinduism welcomes all religions. Our ancient holy men knew that goal is the same; the only question is how we get there and there is no reason to fight or kill over this. (The writer, a physicist who worked in industry and academia, is a Bengali settled in America.)