Ben Stokes in contention to assume leadership of England’s white-ball team

England’s white-ball cricket is at a crossroads following Jos Buttler’s resignation as captain after a dismal Champions Trophy campaign.

Hyderabad had had a quintet in the 1971 contingent inclusive of Abbas Ali Baig, K Jayantilal, P Krishnamurthy and S Abid Ali and the fifth one in the line-up, Devraj Govindraj

SNS | NEW DELHI | September 11, 2021 8:20 pm

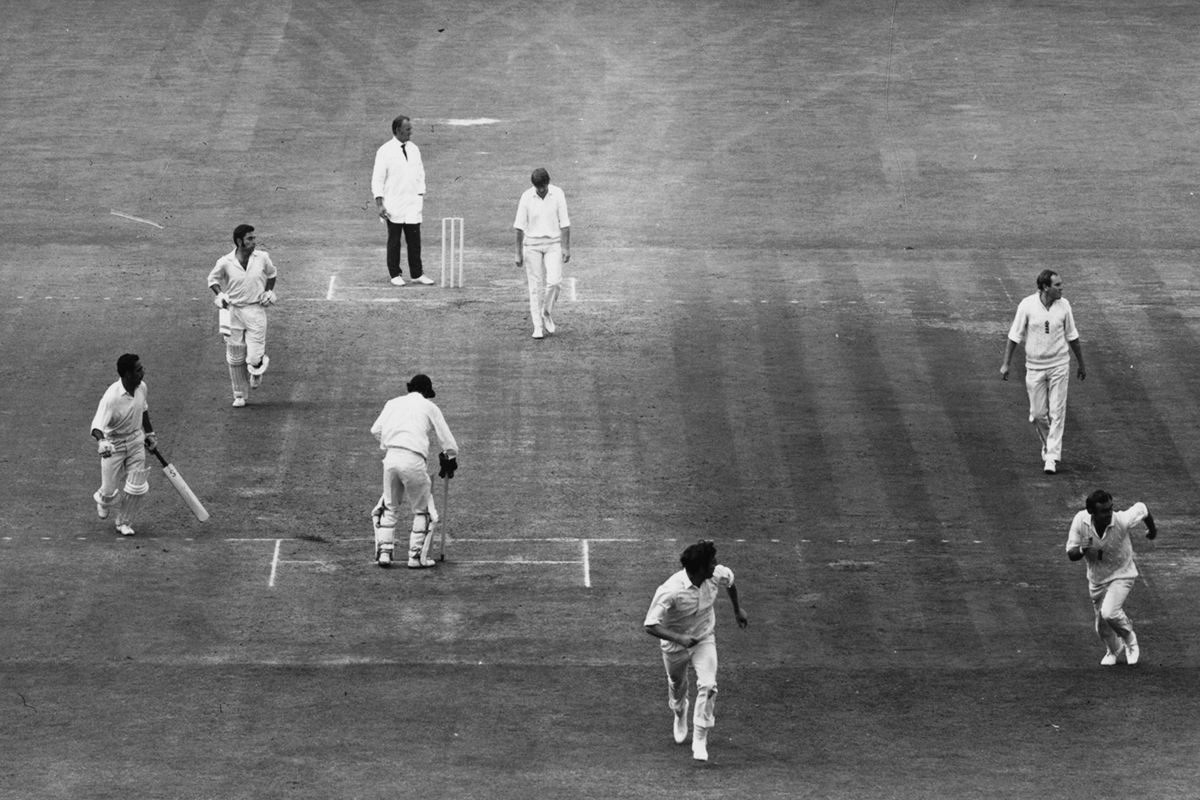

If nostalgia sweeps over us, delightfully entwining the 1971 victory at Oval with the 2021 one there to induce just the sort of effervescence that risks bypassing facts given that the present tends always to appear glossier than the past, chances are posterity could suspect us of ignorance. Here is why. Hyderabad had had a quintet in the 1971 contingent inclusive of Abbas Ali Baig, K Jayantilal, P Krishnamurthy and S Abid Ali and the fifth one in the line-up, Devraj Govindraj, recently said that captain Ajit Wadekar had not really been aiming at a triumph that would shake the world. The historic first-time winner earlier in the West Indies spoke of a drawn Test and series as the team’s collective ambition, considering that too had previously been elusive. But BS Chandrasekhar, the enigma wrapped in a riddle, worked his six-for-38 magic, and that, essentially, had been that. That was spontaneous magic: no schooling in Hogwarts. Superlatives have since quite justifiably been exhausted in celebrating the incredible achievement – it gave us our first Test and series triumph in Blighty ~ but it also makes you wonder what someone like the late Bob Woolmer, whose The Art and Science of Cricket, with its overwhelming new-age emphasis on psychological priming, would have made of it. Neither Chandrasekhar nor Wadekar made a goshawful fuss. No abrasive rhetoric, hardly any combative posturing and no ruptured relationships anywhere along the way but the job was done to everybody’s satisfaction. Magniloquence was unheard of. Belligerent babble might have been deemed suggestive of some mental disorder. 1971 was not 2021. And the two successive spin-reliant overseas victories in those days also stirred a wider debate which pitted the advocates of spin claiming parity with pace for their choice on the basis of the results. It ended when India performed very shabbily in 1974 in England but the Summer of 42 was also about batting failures in equal measure. It is not as if the collapses have passed into history’s small-print footnotes ~ look up the latest results ~ though skipper Virat Kohli’s boys would have gleefully watched England’s dramatic second-innings slide in the fourth Test from a position of considerable comfort much in the same way as often in the Indian Premier League of Twenty20 cricket. The drama, contrived or not, adds spice of a sort nowadays to a game that was not conceived as an extension of television entertainment. And England dropped six catches in the two Indian innings at the Oval this time around, some of them dollies at Test level. India should have won the Old Trafford match for a 3 -1 triumph if it were played. It was not beyond them, partly because England were quite depleted. Equally truly, that would not have vindicated the exclusion from the first-choice XI of Ravichandran Ashwin, who could not get in despite being the world’s finest off-spinner. The snub was an insult to the selectors too. Chandrasekhar in 1971 and Ashwin in 2021 are different stories. One made things happen. The other is airbrushed out of the scene.

Advertisement

Advertisement

England’s white-ball cricket is at a crossroads following Jos Buttler’s resignation as captain after a dismal Champions Trophy campaign.

The chase was then led by Rassie van der Dussen and Heinrich Klaasen, hitting 72 not out and 64, respectively, while sharing a stand of 127 runs off 122 balls as South Africa completed the chase in 29.1 overs.

Questioning England cricket’s “mindset”, former India cricketer Ravichandran Ashwin slammed their approach towards “sub-continental tours” after the Jos Buttler-led team was shown the exit door from the group stage of the ongoing ICC Champions Trophy.

Advertisement