Can Joe Biden clean up the mess with more debt? The pandemic has left us a terrible mess to clear up. What policies will get us out of the huge debt that we have incurred to pay for the health, wealth and job crises?

2020 was a year of terrible devastation, cushioned only by massive government spending. Aside from the favourite sport of blaming China for everything, each country will have to concentrate on the tough business of getting its economy back to a more even keel.

Advertisement

The latest OECD Economic Outlook published this week showed how bad the situation has become. World output was down 3.4 per cent last year, but OECD sees growth of 5.5 per cent in 2021 and 4 per cent in 2022. However, poorly performing countries will continue to suffer low growth rates. China was the only major country that had positive growth in 2020 (2.3 per cent), whereas the Eurozone was down 6.8 per cent, with severe declines for France (-8.2 per cent), Spain (-11), and UK (-9.9). Amongst the emerging markets, India was down 7.4 per cent, Mexico (-8.5 per cent), South Africa (-7.2) and Argentina (-10.5).

The only bright hope for US growing better in the next two years is due to significant fiscal stimulus, plus faster vaccination. But is this sustainable?

The latest IMF Fiscal Monitor showed that overall fiscal deficits are projected at -13.3 per cent of GDP for advanced economies, -10.3 per cent for emerging markets and middleincome economies, and -5.7 per cent for low-income developing countries. Essentially $14 trillion fiscal support was given in 2020, with global public debt rising to 98 per cent of GDP, compared with 84 per cent in 2019.

In short, almost every country threw money at the pandemic, with very little appreciation whether we are getting value for money. In a panic, doing that is understandable. After the panic, the pain and reckoning must begin in all seriousness.

Note that the US fiscal deficit rose from 6.4 per cent of GDP in 2019 to 17.5 per cent in 2020, an increase of 11.1 per cent of GDP fiscal support to defend a decline of 5.6 per cent percentage points in GDP growth (from +2.1 per cent to -3.5 per cent in 2020). In essence, US fiscal policy pumped 2 per cent of GDP spending to defend 1 per cent of GDP growth.

The IMF estimated that the cost to the US is a rise in gross debt to 128.7 per cent of GDP, far higher than the world average of 97.8 per cent. The comparable Chinese gross fiscal debt was 65.2 per cent of GDP in 2020, just over half of US gross debt.

Is Biden’s $1.9 trillion stimulus package this year too much for comfort? The Republicans certainly are alarmed at the sharp rise in welfare spending and debt, so they voted against the package. The nonpartisan Committee on Responsible Fiscal Budget estimates that the total cost including interest and extensions would amount to $4.1 trillion by 2031. In other words, all stimulus spending cost more than what is shown. From a political point of view, Biden had no choice. If he does not revive the economy and protect his support base, he will lose the mid-term elections in 2022, which would make his second half term a complete lame-duck.

So, from a global strategic perspective, the real issue is not further quarrels between US and China. The key is whether Biden can turn around US long-term competitiveness damaged by four years of Trumpian fumbling on top of Congressional focus on short-term issues, rather than long-term infrastructure and structural weaknesses.

Take fiscal and monetary policies. Former US President Ronald Reagan famously said in 1981 that “government is not the solution to our problem, government is the problem”. Instead, US general government expenditure rose by 78 per cent in constant 2010 dollars from 1981 to 2019, whereas total public debt has increased dramatically from $1 trillion or 31 per cent of GDP when Reagan was President to $27 trillion or 136 per cent of GDP by the end of September 2020.

The Fed’s stated monetary policy goals are to promote maximum employment, stable prices and moderate long-term interest rates. Whilst inflation has been kept low at below 2 per cent per annum and unemployment remains low, long-term interest rates are at record low levels, whilst US inequality numbers have worsened since Reagan from a Gini coefficient of 0.38 in 1981 to 0.48 in 2015. In the meantime, the Fed’s balance sheet, which was $865 billion or 6 per cent of GDP in 2007 rose over eight times to $7.6 trillion or 36 per cent of GDP by March 2021.

That’s not long-term strategy, but fiscal and monetary overdose.

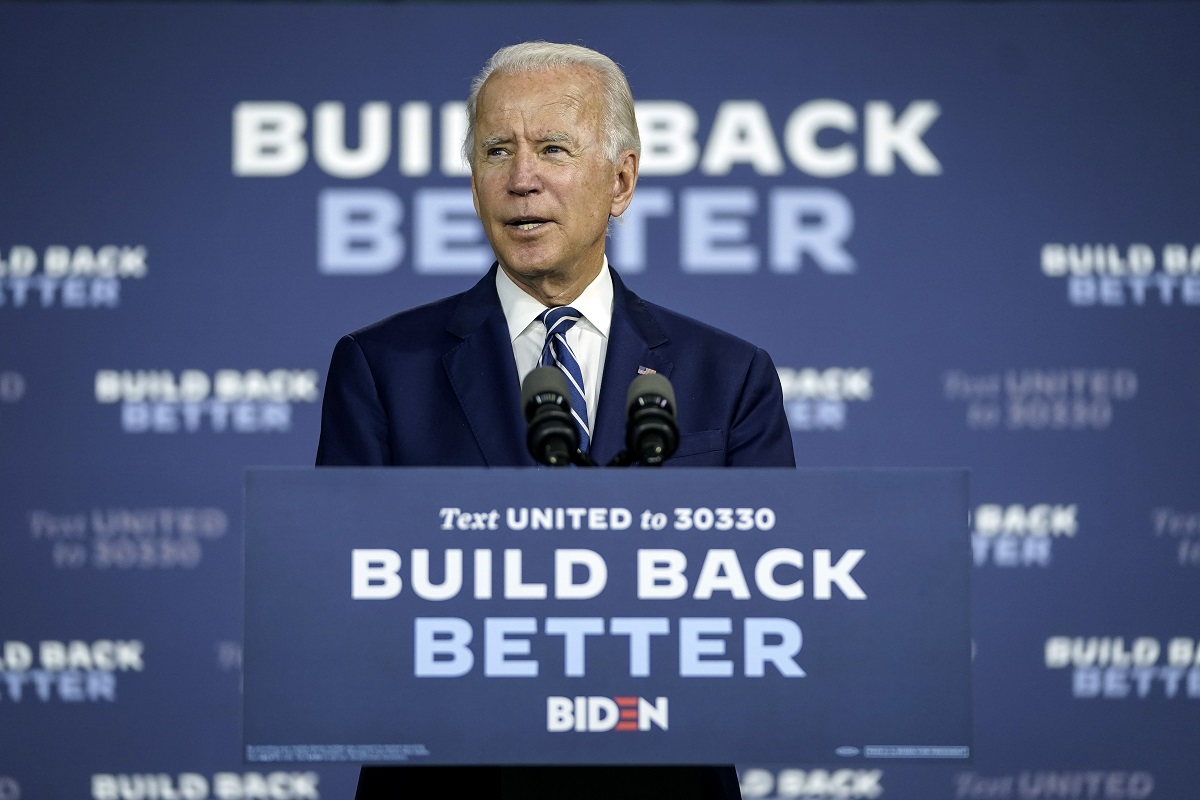

Biden’s Build Back Better programme will spend another $2 trillion during the next four years on building green infrastructure and creating jobs. By comparison, the US spent $686 billion in 2019 on defense alone, and the cost of war since 9/11 for America was $6.4 trillion and 801,000 deaths since 2001. All these are funded by more government debt, which the Congressional Budget Office projects will amount to 202 per cent of GDP by 2051.

Any emerging market with these debt numbers would be called a banana republic.

The Biden Administration is betting that the largest US stimulus package since World War II would restore American competitiveness and heal the nation. But much of this is not funded by domestic savings, such as taxing the rich, but by borrowing on the US dollar. The rest of the world will not fund the dollar forever, certainly not at near zero interest rates. And if interest rates rise, the fiscal costs would be substantially higher. So bet on the Fed pumping more to keep rates low.

Winston Churchill said once, “never waste a good crisis”. But in today’s complex affairs, even experienced journalists have difficulty figuring whether Americans are getting value for such massive government spending. So far, the United States has not spent enough good money on her own people, and more on the war machine. If this opportunity is wasted, then America will be lurching from crisis to crisis.

The truth of US debt is that it is not debt, but the rest of the world’s equity. America is the world’s too-big to- fail borrower. If Biden fails, we lose. Which is why the dollar note says In God We Trust.

The writer is a former central banker and financial regulator. The views are entirely his own. Special to ANN