Nation salutes braveheart Subedar Kuldeep Chand’s martyrdom

The martyr’s mortal remains were sent to his hometown, Kohlvin village in Hamirpur district of Himachal Pradesh.

On Nehru’s suggestion he went to Pakistan and after extensive discussions succeeded in persuading President Ayub Khan to visit New Delhi for talks for a permanent settlement of the Kashmir issue.

ARUN KUMAR BANERJI | August 27, 2022 7:30 am

SNS

The removal of Sheikh Abdullah from power was followed by a succession of Prime Ministers/Chief Ministers (from 1966 onwards) who were indirectly chosen by New Delhi because of their proximity to the leaders in Delhi and for this the Indian government turned a blind eye to their corruption and undemocratic practices. All the elections held in J&K, barring the one in 1977, were rigged. Political opponents who demanded ‘plebiscite’ to determine Kashmir’s future were prevented from taking part in elections and put behind bars, thus muzzling their voices. Suppression of dissent and corruption in administration created resentment among a large segment of the educated middle class, who were not a part of the ruling elite. Despite his ‘modernisation’ and ‘integration’ programmes, Bakshi was removed from power on 11 October 1963 due to corruption and his dictatorial mode of functioning. Nehru looked upon Kashmir as a symbol of India’s secularism.

He believed if Kashmir seceded from India, the fate of Muslims in India would be jeopardized. That Nehru was not really keen on holding a ‘fair and impartial’ plebiscite, despite his formal commitment to it, became clear as early as December 1948 because he was not sure about the outcome. Perhaps it was Indira Gandhi’s letter to her father written from Sonemarg on 14 May 1948 that influenced his decision. She wrote that in Kashmir only Sheikh Abdullah felt confident of winning the plebiscite and argued that mere political talks would not suffice; what was important was gaining peoples’ confidence through economic development. There was also a lurking fear in Nehru’s mind that if India lost the plebiscite, he might lose his job. By removing Abdullah from power and putting him behind bars in August 1953, at a time when he was trying to devise a formula for a plebiscite that would be acceptable to both India and Pakistan, Nehru wanted to foreclose the possibility of Kashmir’s secession from India, while at the same time trying to wipe out the State’s “Special status”.

Advertisement

With the passage of time, a plebiscite in Kashmir, no matter what the UN might resolve, was becoming more and more difficult to implement. In fact, Nehru had been thinking of settling the Kashmir issue on the principle of accepting the status quo, with rectifications of the border that would satisfy both India and Pakistan. He mentioned this during meetings with Pakistan Prime Minister Mohammad Ali Bogra and Interior Minister General Iskandar Mirza in May 1955, and even earlier, during his two meetings with Liaquat Ali Khan in 1948. But for obvious reasons, they did not agree. In February 1954, the J&K Constituent Assembly, while adhering to the special position of the State, passed a resolution confirming the legality of Kashmir’s accession to India. By October 1956, it had adopted a Constitution for the State which became operational from 26 January 1957. It provided for the jurisdiction in the state of the Indian Supreme Court and the Comptroller and Auditor General and declared that the State of Jammu and Kashmir ‘is and shall be an integral part of the Union of India’, despite protests by Sheikh Abdullah from his prison cell, and the UN Security Council.

Advertisement

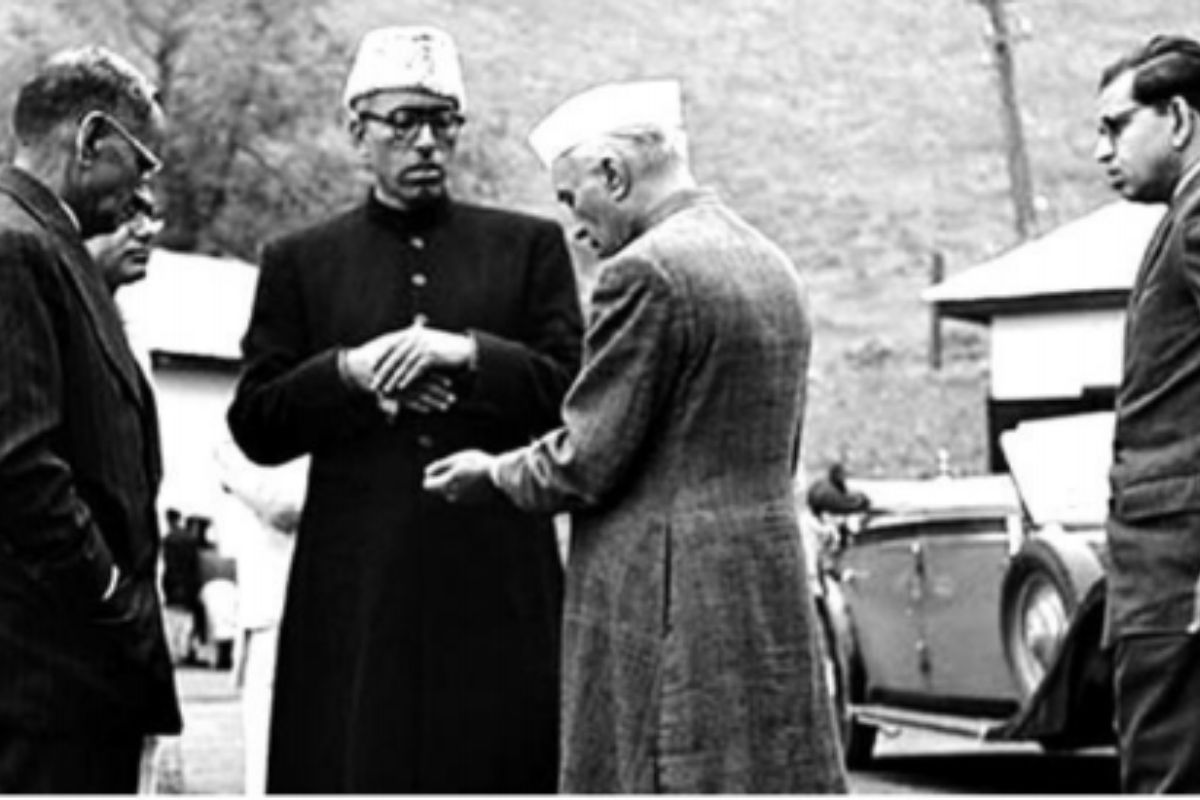

It led to the formation of a new opposition party in the State, the Plebiscite Front, led by Mirza Afzal Beg, one of Abdullah’s close Associates, while reduction in Kashmir’s autonomy proceeded apace, especially during the tenure of Ghulam Mohammad Sadiq as the Prime Minister. By December 1964, Jammu & Kashmir’s position was virtually on a par with other Indian provinces. The autonomy guaranteed under Art. 370 of the Indian Constitution remained a mere fig leaf, with the extension of the jurisdiction of laws passed by Parliament in the Central List, as well as in the Concurrent List, to Jammu and Kashmir. Sheikh Abdullah was released in April 1964, all charges against him were dropped and he returned to Srinagar to a rousing reception. On Nehru’s suggestion he went to Pakistan and after extensive discussions succeeded in persuading President Ayub Khan to visit New Delhi for talks for a permanent settlement of the Kashmir issue. But the sudden death of Nehru on 27 May 1964 ended that possibility.

Sheikh Abdullah was interred again from 1965-68 and the Plebiscite Front was banned, to prevent it from participating in the elections in Kashmir. Finally, the Sheikh was exiled from Kashmir during 1971-72. The India-Pakistan war and the liberation of Bangladesh brought about a significant change in Sheikh Abdullah’s attitude; he no longer talked about a plebiscite for settling Kashmir’s future. An opportunity came in 1975 through the signing of the Indira Gandhi-Sheikh Abdullah Agreement. He agreed to accept Jammu and Kashmir as an integral part of India by getting a resolution passed by the State Assembly on the condition that all the Acts and Ordinances issued by New Delhi since 1953 would be reviewed. Sheikh Abdullah returned to power as the Chief Minister in 1975. But the agreement was never placed before Parliament, nor did the promised review take place. New Delhi’s attitude towards the State had always been determined by the exigencies of the political party in power at the Centre, be it the Congress or the present ruling dispensation in New Delhi.

The dismissal of the legitimately elected government of Dr Farooq Abdullah in 1984 was engineered by New Delhi and a new government led by G M Shah was put in place, with the support of the Congress leadership in New Delhi as well as in Kashmir, although it led to widespread protests in the Valley and threw J&K politics in turmoil. Following widespread communal violence in South Kashmir, which many people believe was instigated by some disgruntled Congressmen, the G M Shah government was dismissed, and Governor’s rule imposed. Dr Farooq Abdullah was reinstated in power in November 1986 under the Rajiv GandhiFarooq Abdullah accord which was criticized not only by the old guard in both parties but also by Maulana Mirwaiz Farooq, Chairman of the Awami Action Committee. He criticized it as a sellout to the Congress.

Soon after assuming office, Dr Abdullah advised the Governor to dissolve the Assembly and in elections held in March 1987, besides the National Conference and the Congress, the Muslim United Front (MUF), viewed by many as a spontaneous local political formation, without any links with the Congress, also participated. It was expected to do well as a debutant political party as people were fed up with years of ‘family rule’, corruption and lack of economic development. However, the elections were allegedly rigged to prevent the Congress from losing its control over Kashmir and a coalition government was formed with the National Conference and the Congress. The rigging of elections triggered the violent insurgency in Kashmir towards the end of the 1980s and early 1990s as many of the frustrated MUF leaders took to arms and fled to Pakistan for military training, supply of arms and diplomatic and financial support, and our neighbour took full advantage of this.

India’s Kashmir problem is the result of the follies of our political leaders, both at the Centre and in the State, their lust for power, creating anger and resentment among the people that gave Pakistan opportunities to fish in troubled waters. Abolition of Article 370, through a ‘surgical strike’ launched by India’s Home Minister on 5 August 2019 has not brought about any substantial improvement in the situation on the ground and even 75 years after independence the Kashmir problem remains unresolved.

A version of this story appears in the print edition of the August 27, 2022, issue.

Advertisement

The martyr’s mortal remains were sent to his hometown, Kohlvin village in Hamirpur district of Himachal Pradesh.

People in Srinagar, Jammu, Shopian and several other parts of Kashmir region felt the tremors.

The martyred JCO has been identified as Subedar Kuldeep Chand of the 9 Punjab.

Advertisement