Immediately after the signing of the ‘Delhi Agreement’, Sheikh Abdullah proceeded to abolish the institution of hereditary monarchy and got the necessary resolution passed by the State Constituent Assembly on 21 August 1952. While abolition of hereditary monarchy in J&K was consistent with the Congress Party’s ideology, Sheikh Abdullah’s move to depose Maharaja Hari Singh and prepare for his possible impeachment for anti-State activities raised a political storm, particularly in Jammu. It seems, in retrospect, that the ‘Delhi Agreement’ was a part of the strategy that Nehru had adopted to satisfy Abdullah’s vision of Kashmir’s ‘autonomy’ as New Delhi did not want to alienate him at a time when the Kashmir issue was still on the agenda of the UN Security Council. But Nehru himself was not too keen on maintaining this ‘autonomy’ for Kashmir, especially after Sheikh Abdullah’s attitude towards Kashmir’s future became ambivalent as he was toying with the idea of an independent Kashmir which becomes evident from the report of the US Ambassador, Loy Henderson (September 1950), and this attitude developed further due to developments in J&K.

The right wing within the Congress and other right wing/ communal forces in the country were opposed to the Delhi Agreement as they wanted total integration of J&K with the rest of India and some of Sheikh Abdullah’s actions gave fillip to the activities of these forces. One of these was Sheikh Abdullah’s radical land reforms programme, particularly the enactment of the Big Landed Estates Abolition Act (1950). It placed a ceiling on land ownership at 186 kanals (approximately 22 acres). The rest of the land of the landlord would be distributed among share-croppers and landless labourers, without any compensation to the landlords. These reforms caused a social transformation within the Valley, where most of J&K’s fertile lands are concentrated, and the farmers were cruelly exploited by the landlords, mostly Hindus ~ either Dogras or Pandits.

Advertisement

Although the benefits of the reform did not always reach the intended beneficiaries in subsequent years, because of corruption at the level of implementation, the reforms consolidated the National Conference’s support base, particularly in the Valley, and increased Sheikh Abdullah’s popularity. But it also created problems. As David Devadas wrote later, an incisive study of the leadership and cadres of the most strident anti-State groups of the past would show ‘that many former landlords turned to such groups.’ In Jammu, an attempt was made by the critics of Sheikh Abdullah to give a communal colour to his land reforms policy, since the beneficiaries were mostly Muslims, while the landowners were mostly Hindus, although Abdullah assiduously sought to deny this. His ambivalence towards the question of Kashmir’s future only served to ignite Hindu communal resentment.

By the end of 1952, Praja Parishad, the Hindu communal party in Jammu, started a violent agitation demanding full integration with India to solve the Kashmir problem and was joined by the Jan Sangh, newly founded by Dr S P Mukherjee, the Hindu Mahasabha, the RSS and the Akali Dal. The agitation in Jammu soon spread to Punjab, Delhi and beyond with the addition of two other issues: refugees from East Bengal and a ban on cow-slaughter. Nehru, in his speech in the Lok Sabha on 25 April 1953, termed the movement ‘most pernicious and malignant’ in its ‘narrow, bigoted, reactionary and revivalist’ approach and pointed to its dangerous repercussions. These developments needed firm actions by the central government at different levels; but they were lacking.

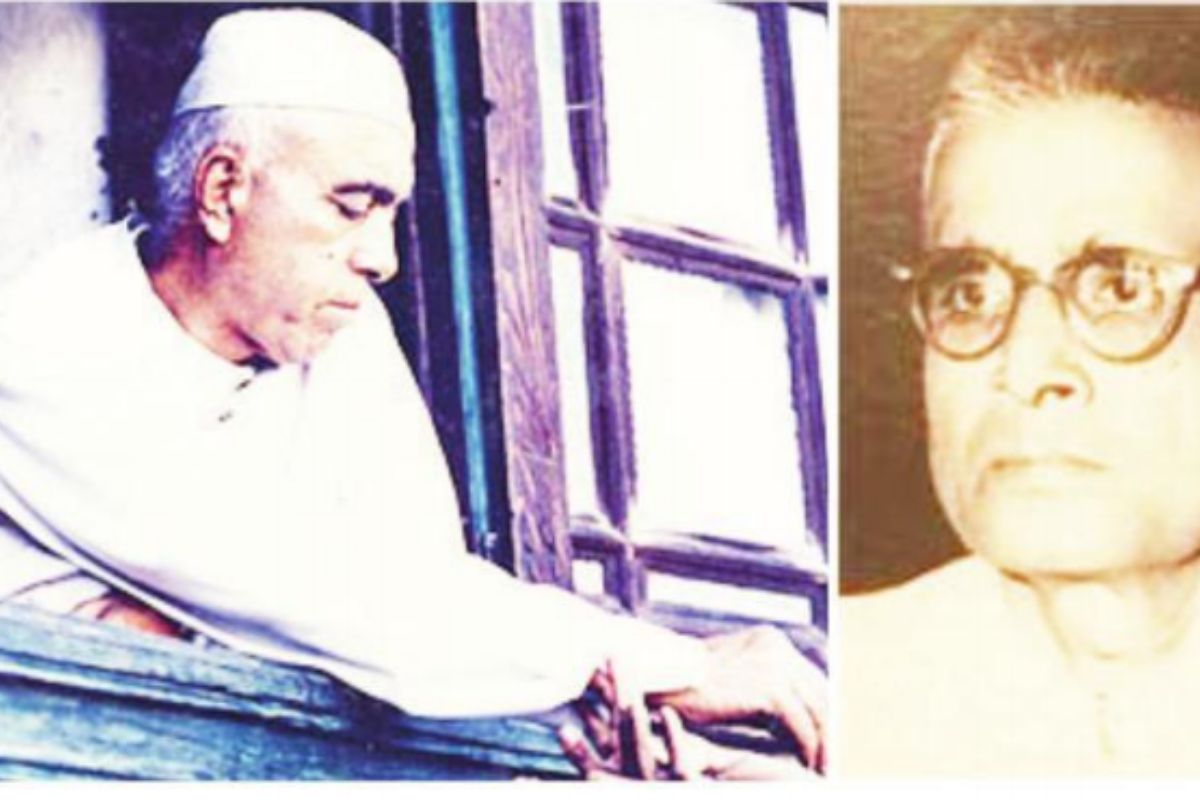

On 25 July 1953, Abdullah said that as a result of the Praja Parishad agitations, joined by the Jan Sangh and other communal parties, the confidence which the National Conference had created among the people about Kashmir’s accession to India, had been shaken, and created discontent among many of his party men. Earlier, on the Martyrs’ Day (13 July 1953) during his speeches at huge public rallies, Sheikh Abdullah stated that Kashmir’s accession to India was a mistake and that he no longer trusted Indian rulers. He ended by saying: “we have different ways now.” Such utterances of Sheikh Abdullah and his authoritarian style of functioning created a flutter in New Delhi and plans were afoot for his removal for which a coterie of men from Abdullah’s own Cabinet ~ led by the ‘pro-India’ Deputy Prime Minister Bakshi Ghulam Mohammad and including D P Dhar, S L Saraf and others ~ was chosen, with active support from B N Mullik, the IB chief.

On 7 August 1953 three members of the government led by Bakshi, submitted a memorandum to the head of State accusing Sheikh Abdullah of making arbitrary decisions and holding him responsible for the deteriorating law and order situation. The coup de grace was delivered on 9 August 1953 with the unceremonious dismissal of Abdullah from the position of Prime Minister by the Sadr-iRiyasat, Karan Singh, on the ground that he had lost the support of the majority in the Cabinet, followed by his imprisonment, apparently on the orders of Nehru. Bakshi was appointed the Prime Minister and after assuming office he stated that Sheikh Abdullah’s policy of independence which had the support of interested foreign powers, would be a threat to the interests of the people of India and Pakistan.

Praising India, he declared that India and Kashmir had established ‘indissoluble links’. By arresting the ‘Lion of Kashmir’ without giving him any chance to prove his majority in the State Assembly, New Delhi created a great psychological chasm between the Kashmiris and the rest of India. It is alleged that Mullik had played a dubious role in the whole episode. When he met C Rajagopalachari a few months after the arrest, Rajaji felt strongly that Abdullah should have been given a third alternative of autonomy or even semi-independence, without shutting the door which, he apprehended, would contribute to unrest and continued uncertainties.