India’s Got Latent: SC issues notice on YouTuber Ashish Chanchlani’s plea against FIRs

SC issues notice on YouTuber Ashish Chanchlani’s plea to quash or transfer FIR in India’s Got Latent case; tagged with Ranveer Allahabadia’s petition.

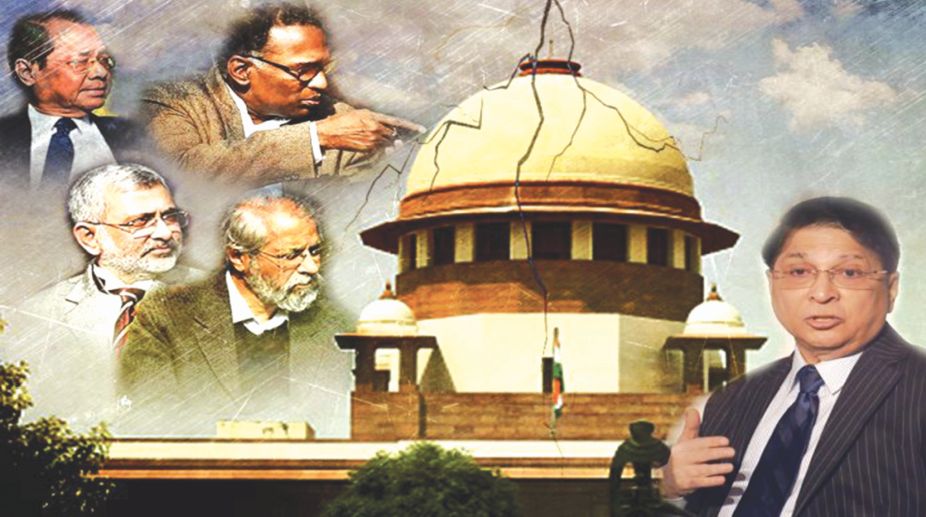

Supreme Court

Exposing a rift with Chief Justice Dipak Misra with respect to the allocation of cases, the four senior-most Supreme Court judges have highlighted serious administrative issues that may require public attention. Justice Jasti Chelameswar said at a press conference, ‘The four of us are convinced that unless this institution is preserved, and it maintains its equanimity, democracy will not survive in this country,’ A keen observation of the circumstances in which Justice Chelameswar had to make this rather grave statement should reveal the NJAC judgment of 2015 as one of the reasons culminating in the present controversy.

The open letter by the four senior judges is an unprecedented and radical move with obvious but severe implications for India’s democracy. While some members of the legal fraternity criticise the public nature of the rift as ‘trade unionism’, others welcome it as an important and a necessary action taken by the Judges to safeguard the core democratic values of the country.

Advertisement

Karuna Nundy, a renowned Supreme Court lawyer, praises the move as one of the first steps ‘to correcting an institution by looking at its own flaws and deepening… constitutional democracy.’ On the other hand, Soli Sorabjee, the former attorney general of India, states that the administrative issues could have been resolved internally, and the public shouldn’t have seen the judiciary as a divided house.

Advertisement

These arguments seem to be a clash of integrity and transparency as essential features of any judiciary versus dignity and authority of the judiciary in the public eye with no middle ground discovered as yet. Amidst this quandary lies the legal-factual question of whether the Chief Justice overstepped his powers as ‘first among equals,’ compromising the trust vested by the people in the judiciary.

In his dissent in the National Judicial Appointments Commission (NJAC) 2015 decision, Justice Chelameswar drew attention to the egotism of the Supreme Court under the garb of ‘basic structure’ and ‘independent judiciary.’ Transparency, as identified by Justice Chelameswar, is a pivotal characteristic of judicial proceedings. Although the framework of the NJAC is far from being a fool-proof mechanism, the rather patent biases that plagued the judiciary for some years now required scrutiny by not just the judiciary itself but also by bodies belonging to the other organs of the democracy as suggested to an extent in the NJAC model.

Justice Chelameswar observed that the complete exclusion of the government in judicial appointments is inconsistent with constitutional democracy. Despite his dissent, the Supreme Court once again affirmed its exclusive powers in determining the appointment of judges. This marked one of the initial warnings towards the current circumstances with the allegations of arbitrariness against the Chief Justice at the centre of attention.

While there needs to be a fully functioning interplay of the judiciary, the legislature and the executive to scrutinise each other’s jurisdiction and powers, the executive doesn’t appear to be adequately concerned about the task of fulfilling the checks and balances doctrine.

When the Supreme Court struck down as unconstitutional the NJAC Act 2014 as passed by the Parliament, it saw the need to send to the government a Memorandum of Procedure (MoP) for appointment of judges to members of the higher judiciary. As specified in the letter sent by the four Supreme Court judges, the then Chief Justice of India sent the finalised version of the MoP to the Central government in March 2017. It has been more than 11 months and the government still hasn’t responded to the MoP. This tardiness of the executive raises dangerous questions about its very credibility as a pillar of democracy.

To sum up, the submission of the four senior-most judges to the nation indicated the tipping point reached by them regarding the opaqueness in the Court’s proceedings, as exemplified by the Chief Justice’s preferential roster. It seems like a move emerging out of despair and an indication to the nation not to be blindsided by the apparent respectability of the Indian judiciary. A series of reasons that came both before and after the NJAC judgment culminated in the press meet on 12 January 2018. However, the role that the NJAC judgment has played has largely been ignored by the media and hasn’t been sufficiently discussed by legal commentators.

The writers are, respectively, professor of law and a fourth-year law student at Jindal Global University in Sonipat.

Advertisement