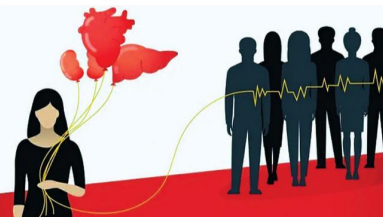

Every year, in India, about five lakh people die due to the non-availability of organs. As per a news report, “Only around 39,000 organ transplants were conducted in 2020 against the requirement of at least 15 times”. The criterion used for a kidney transplant is emblematic of how the current organ transplant system favours the socio-economic “haves” and disadvantages the “have nots”. In India, kidney transplant has two sources, a living donor and a deceased donor. Logically and rightly so, donations from deceased donors form the thrust of government policy.

Yet in cases where patients depend on a deceased donor, there is a long waitlist. There is an elaborate Allocation Criteria for Deceased Donor Kidney Transplant laid down by the National Organ and Tissue Transplant Organization (NOTTO). There are multiple equityrelated issues in the kidney transplant regime in India.

Advertisement

Firstly, a patient needs to be less than or equal to 65 years of age at the time of registration. Besides being a criteria that may be considered ageist, there may be some defences to this, given that the overall life expectancy in India is at 70.8 years as per the World Health Statistics 2021 report.

Yet it is hard to assume an individual’s longevity based on national averages. Further, life expectancy for women in India is 2.7 years higher than men as per the same report and therefore the cut-off puts elderly women at a relative disadvantage over men, if averages are somehow to be believed as valid criteria. Further, with advances in overall healthcare and nutrition, and specific advances in geriatric care, life expectancy in India is forecast to increase to 80+ years by 2050.

The increased life expectancy each year would posit the need for a proportional increase in the cut-off each year. Prof. George J. Annas of Boston University in a 1985 paper tells the story of 1984 Britain when the unwritten practice became highly publicized that general practitioners would not refer patients of 55 years or above for dialysis or transplant. This meant that there were 1500-3000 “unnecessary deaths” annually. This led to movements to enlarge the National Health Service budget to expand dialysis services to meet this need, a more socially acceptable solution than permitting the now publicly recognized situation to continue.

In India, we have changed the unwritten rule to a written one. But it does not make it any less unfair. Culturally, we seem to believe that the aged have lived their lives and therefore, their lives are somehow worth less than the younger lot. By 2050, we may have nearly 20 per cent of our population in the senior citizen category and these cultural assumptions may not hold true with changing times.

Secondly, as per the NOTTO criteria the patient should be a case of End Stage Renal Disease (ESRD) on maintenance dialysis for more than three months on regular basis. This criterion does not take into account the financial burden of dialysis on poorer sections of the population and the lack of accessibility to the treatment. The number of hemodialysis (HD) centres in India were estimated to be at 12,881 in 2018 and these too are concentrated in urban areas and in private hospitals. In a country where “two thirds of the population lives in rural areas where the availability of HD is limited”, the criteria of being on dialysis for three months is exclusionary and breeds iniquity.

Further, “almost 60 per cent of patients on dialysis” have to travel more than 50 km to access HD, and “nearly a quarter lived >100 km away from the facility” (Jha et. al, 2019). Indeed, this results in increased costs and loss of wages thereby making it difficult for economically weaker patients to access dialysis. Researchers like Vivekananda Kha note that the National Dialysis Program 2016, that envisaged setting up an eight-station dialysis facility in all 688 districts of the country to provide HD to poor patients would be inadequate.

“If patients were dialyzed twice a week (which is commonly done in India), only about 50,000 new patients (representing about a third of the current requirement) would be accommodated under this program, even without future growth.” To be fair, the “Criteria of urgent listing” lays down the first principle for urgent listing as follows: “In case of kidney transplant, urgent list is basically for a patient who no longer has dialysis access and thus cannot be maintained on dialysis”. In practice, however, this criteria is not adhered to owing to capacity issues and lack of access to even reach HD stations for poor patients.

In a report titled, “Dedicated teams, cost, facilities — why pvt hospitals do over 75% of organ transplants in India”, Abantika Ghosh observes that “help from the Prime Minister’s National Relief Fund is available to people from economically weaker sections, usually with the proviso that the patient or family would arrange part of the funds.”

Further, “organ recipients also have to be on immunosuppressive drugs for the rest of their lives, and that can cost anything between Rs 10,00 and Rs 15,000” and this can again be prohibitively expensive for the poor.

The national-level minimum wage is around Rs 178 per day, which works out to Rs 4628 per month assuming 26 days of work. Finally, the allocation algorithm defining the criteria for urgent listing seems biased in favour of private hospitals. Who gets the kidney depends on whether they and their deceased donor belong to a private or a government hospital. The algorithm is as follows: 1. Kidney retrieved from a government hospital will be allocated as follows:

- First patients listed in Government ONLY hospitals list, then

- Patients listed out of combined government and private hospital list, then

- Patient listed out of private ONLY hospital list 2. Kidney retrieved from a private hospital will be allocated as follows:

- First patients listed in private hospitals list, then

- Patients listed out of combined government and private hospital list, then

- Patient listed out of government hospital list

If kidneys retrieved from donors from private hospitals are allocated on priority to patients listed in private hospitals, it creates an equity deficit too. In a country where most hospitals are in cities, and most deceased donors are to be found in private hospitals, the economically better off patients who more often tend to be registered through private hospitals than government hospitals have an unfair advantage.

For example, according to a recent (May 2022) report by Sumitra Debroy, in Mumbai “Barely 2% of cadaver organ donations in the city have been facilitated by public hospitals in the past five and a half years”. Tweaking the algorithm in favour of government hospitals is perhaps the more equitable and just alternative given the Indian context.

Further, it is always and evermore important to generally increase access to HD centres and other health facilities in rural areas. Another effective way to address the problem of access and equity is wider adoption of government-sponsored health insurance schemes in southern states such as such as Tamil Nadu, Kerala, Puducherry, Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, and Telangana which have ensured that “tertiary care hospitals provide maintenance hemodialysis, transplantation and follow-up either at very subsidized rate or free of cost and hence they cater to the lower socio-economic sections of the society.” Lottery systems, ethical-marketbased approaches, and ethical screenings of committee decisions have long been debated and offer interesting elements of thinking about making organ donation and transplants more equitable.