History has a tendency of repeating its worst aspects. This appears particularly true for us; headlines in India do not change ~ year after year. Be it the news ‘Saina Nehwal loses in the finals’ or ‘Dozens killed in train tragedy’ or that ‘Development of Indian fighter aircraft/battle tank would take a few more years’; the same news is repeated endlessly leaving one wondering if one was reading today’s newspaper or last year’s.

One headline, with some variation, that is repeated many times in a year is: ‘X Organisation rated India in the bottom ten countries of the world’ which is invariably followed by another headline: ‘Government rejects X Organisation’s biased report.’

Advertisement

Our thin skin for any unfavourable comment or advice prevents us from seeing that despite our claims to the contrary, we are yet to achieve economic equality or social justice, which is the cause of our low rating vis-a-vis human development indices. Instead of stimulating introspection, reports of internationally respected bodies, that point out our shortcomings on social justice issues are routinely ‘rejected’ by the Government of India notwithstanding the fact that none of these reports were ever sent for the Government’s approval.

The Thomson Reuters Foundation report on women’s safety, which ranked India at the bottom, the World Bank’s report on Human Capital Index which ranked us almost at the bottom, are amongst the many reports that have been summarily rejected. The Government pays little heed to the informative value of well-researched reports that highlight the deficiencies in our social welfare programmes. On the other hand, reports that show us in a good light like the Ease of Doing Business Report, are gladly accepted and tom-tommed as proof of our great achievements.

Almost unanimously, various researchers measuring wealth (Chancel-Piketty, Credit Suisse etc.) have concluded that most of the wealth being created in India is going to the already rich, making India the second most ‘unequal’ country in the world (after Russia). These reports also got the royal cold shoulder but according to our own Income-tax statistics, the number of individuals paying more than Rs 1 crore as incometax has increased by 68 per cent in the last four years. Since our GDP has not increased correspondingly these statistics validate the conclusion drawn by foreign researchers viz. the poor have been left far behind in all respects in our society, belying the sabka saath sabka vikas slogan of the Government.

Our poor performance in the human development sphere is surprising given the fact that in addition to the money spent by State Governments, the Central Government alone spends almost Rs 12 lakh crore per year on social development programmes. Our bureaucracy, which decides the where and how of public expenditure, is squarely responsible for this profligacy. We would have to change our bureaucratic work ethic if we wish to derive any significant benefit from the humongous amount of money we are spending on welfare activities.

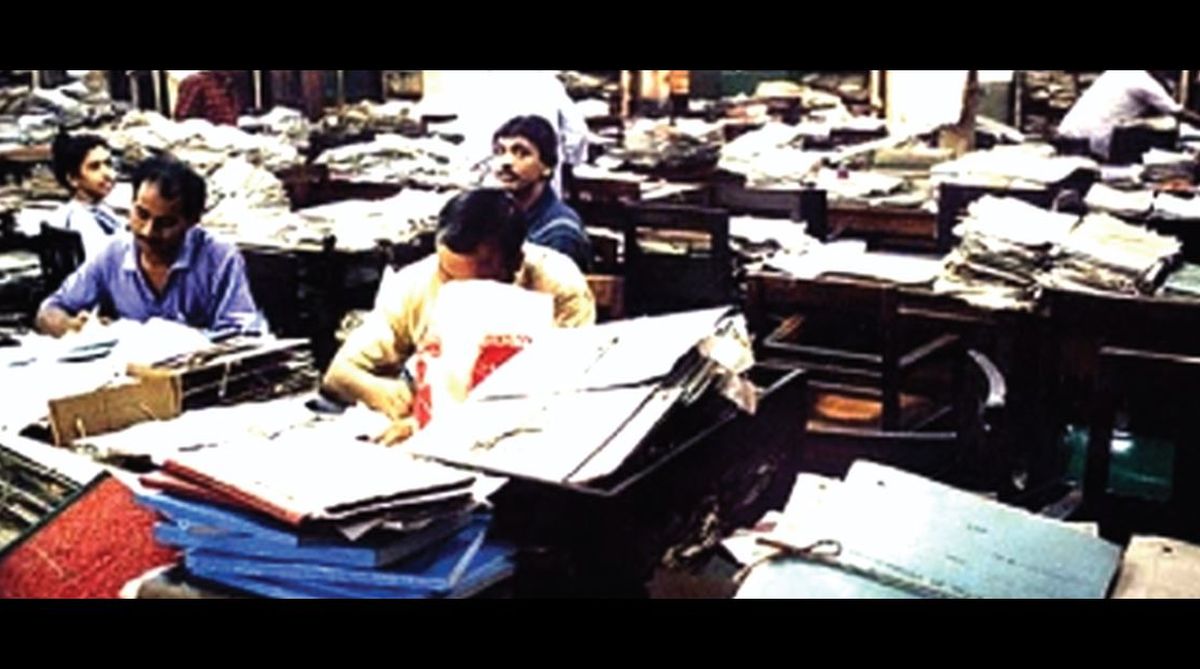

As a first step, lack of accountability of Government functionaries has to end. At present, Government decisions are taken on files which pass through many hands, diffusing responsibility to the extent that responsibility cannot be fixed even for the most outrageously wrong decisions. Departmental rules and circulars, which guide Government business, are hopelessly outdated and in many cases contrary to each other. One often finds that even senior officers lack initiative, seeking justification for their actions in some manual or circular. If precedents are not available the Government machinery goes into panic mode or lapses into masterly inactivity.

No one dares suggest that the file system has degenerated to the extent that in important cases a junior functionary writes a note dictated by his bosses which sails through effortlessly. When things go really wrong the file simply disappears. In any case, the person holding the file decides when the file would start its upward journey and when the file should go into coma. Unfortunately, in the much-publicised Vodafone case the Supreme Court has held that for any transaction, the form of the transaction is more important than its substance, which promotes sophistry at the cost of work.

The current bureaucratic ethos promotes inefficiency to the extent that Government functionaries make sure that rules are followed even if nothing gets done. Reversing this approach would require scrapping the plethora of rules and circulars in every government department and trusting the discretion of the man on the spot. Freed of the need to comply with an overabundance of directions, officers would be able to make use of their native intelligence and experience. Since a number of persons would not be involved in every decision, there would be more accountability and less delay.

Instead of having voluminous physical files with myriad notings, then we would have digital files where only the person taking the decision would write down why he was persuaded to a particular point of view. Digital files would not suffer from the disadvantages of physical files because digital files cannot be lost or corrupted and authorised persons would easily view the contents of digital files even from afar.

In this scenario, bureaucrats sitting in ivory towers in Delhi would be required to assume responsibility instead of merely pontificating in Queen’s English and indulging in power games; the army of deskbound clerks in every Government department could be put to pasture or deployed in roles where they would be required to engage with the problem at hand and not just record inane comments.

Contrary to what has been the practice so far, Gandhiji was always against unilaterally deciding what was good for village dwellers. Writing in Harijan in 1936, the Mahatma had said: “The only way is to sit down in their midst and work away in steadfast faith, as their scavengers, their nurses, their servants, not as their patrons, and to forget all our prejudices and pre-possessions.” Putting Gandhiji’s thinking in action would mean planning from bottom up rather from top-down.

Instead of Soviet style pan-India programmes, conceptualised by bureaucrats in Delhi, villages or groups of villages would identify their problems and needs and district-level plans could be formulated accordingly. Implementation and monitoring would be much easier because of the small size of projects and the small number of people involved.

Village level planning would be one step towards the Gandhian concept of Village Republics where villages are self-governing and self-dependent. To appreciate the value of this change, one only needs to remember the time before the RTI Act when beneficiaries of Government expenditure did not even know what had been done for them and at what cost.

Political parties in India spar over non-issues but seldom disclose their vision for the country. Sometimes, political parties release their election manifesto at the eleventh hour. To ensure that a purposeful government is elected, the Election Commission should mandate that before elections, all political parties should have a public debate on their vision for India and how they aim to achieve it.

Public servants should be taught to cultivate initiative so that they come out of their colonial heritage of subordination which make them good followers but bad administrators. Till our leaders have vision and public servants have initiative, our country would be like the ship which sails where the wind takes her; we can chart our chosen course only by our own intelligence and resources. When doubts set in, we can refer to the advice of Mahatma Gandhi: “Recall the face of the poorest and weakest man you have seen, and ask yourself if this step you contemplate is going to be any use to him.”

The writer is a retired Principal Chief Commissioner of Income-Tax.