India-Egypt Joint Special Forces exercise CYCLONE-III kicks off in Rajasthan

The third edition of the India-Egypt Joint Special Forces Exercise - CYCLONE-III - is currently underway at the Mahajan Field Firing Range in Rajasthan.

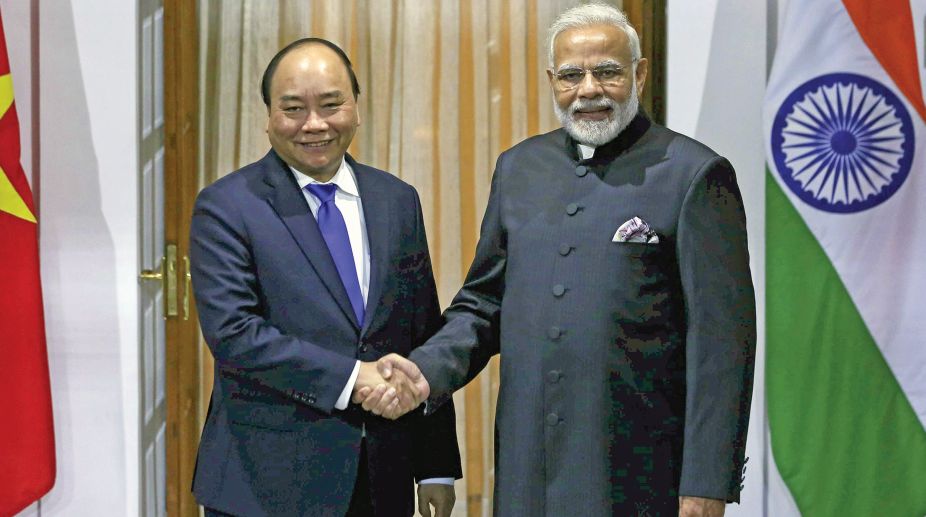

Vietnamese Prime Minister, Nguyên Xuân Phúc and Prime Minister Narendra Modi

The recent visit of the Vietnamese Prime Minister, Nguyên Xuân Phúc to New Delhi to attend the Asean-India Commemorative Summit and participate in the Republic Day celebrations has added a new dimension to the bilateral engagement. If one looks closely at the intensity of India-Vietnam relations in the near past, one can easily decipher that it truly exemplifies a pro-active approach. In 2016, the two countries agreed to upgrade their level of engagement from being strategic partners to a “comprehensive strategic partnership”.

The nature of this engagement is largely geo-economic, and it is an instrument to serve the economic as well as geopolitical interests of both countries. India offered a $500 million defence line for credit to Vietnam in 2016. Also, several agreements including those on off-shore patrol vessels, cyber security, construction of an army software park, United Nations peacekeeping, and scholarship for higher education were also signed. In fact, owing to the momentum set forth by Prime Minister Narendra Modi on various bilateral issues including extending thedefence line of credit, gaining a “strategic depth” in bilateral socio-economic and geopolitical pursuits now seems inevitable.

Advertisement

Moreover, the contentious geopolitical issues in the region are also reflected pragmatically in this comprehensive strategic partnership. For instance, India has also expressed its concern about the freedom of navigation in the South China Sea, and in 2016 also supported the verdict of the Permanent Court of Arbitration of the International Court of Justice. Last year, on the sidelines of the Asean summit, Prime Minister Modi held talks with Prime Minister Phuc and both leaders stressed on deepening the bilateral relations. Most recently, we have seen a call from Vietnam inviting newer Indian investments in the oil and gas sector in its exclusive economic zone (EEZ) in the South China Sea, which could open up another chapter in our engagement in the South China Sea.

Advertisement

It is however pertinent that both countries devote more policy space to at least five key geo-economic issues that have the potential to create synergies as well as pragmatic outcomes. First and foremost is the issue of participation in the global value chains (GVCs). This is highly pertinent because more than 60 per cent of the international trade today happens in intermediate goods. The production networks and value chain activities are geographically spread across a region based on raw material availability, market size and cost advantages. But statistics reveal that the participation of both India and Vietnam is relatively less than their true potential. The two countries should collaborate with each other in enhancing their GVC participation especially in sectors such as apparel, footwear, electronic goods, and even petrochemicals.

Secondly, bilateral engagement needs more policy space in the small and medium enterprises (SMEs) sector to guide their participation in the GVCs. The institutional frameworks including industry chambers, and the role of regional congregations like Mekong-Ganga Cooperation (MGC) and that of India and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (Asean) free trade agreements (FTAs) in goods as well as in services have immensely contributed to the development of bilateral cooperation. Moreover, the policy frameworks like the “Look East Policy” and now its successor “Act East Policy” too are being leveraged well by the government to boost India-Vietnam bilateral ties. Nonetheless, the focus now should potentially be on creating SME clusters linked to multinational lead firms. With improved investments and market access, this will help create avenues to address even SME related challenges like adapting to global demand, availability of finance, managing supply-side constraints, innovation, access to technology, reducing carbon emission, among others.

Thirdly, the cooperation in services sector needs a boost. India’s global exports of services is $161.8 billion, while Vietnam’s global services exports stands at $12.38 billion as of 2016. Vietnam’s economic activities are quite consistent in terms of the participation in the gross domestic product (GDP). Agriculture sector makes a 15.9 per cent contribution to Vietnam’s GDP, while industry contributes 32.7 per cent and services sector is also quite upcoming with 41.3 per cent. With such a structure, Vietnam has huge potential to develop its services sector especially information and communication technology, financial services, tourism, audio-visual services, logistics, and even higher education in collaboration with India.

Fourthly, the diversification of bilateral trade basket remains a concern. India’s exports to Vietnam in 2016-17 increased by 28.87 per cent over the previous year. And interestingly, Vietnam’s exports to India also increased by 29.69 per cent. The bilateral trade stands at $10.11 billion, which is again a 29.14 per cent increase from the previous year. All these statistics clearly reveal that this bilateral engagement has created a win-win situation for both the countries. Last year, President Pranab Mukherjee also called upon the two countries to work toward a $15 billion target for bilateral trade by 2020. This target seems quite achievable given the intensity and the level of ongoing cooperation. However, most of the bilateral trade is only in conventional sectors of our respective comparative advantages like fish and crustaceans, rubber, cotton, edible meat and offal, OEMs, electrical machinery and parts etc. But we need to develop our bilateral trade portfolio based by creating newer competitive advantages in other sectors as well.

Finally, few common yet strategic instruments need utmost and continuous policy attention from both sides. The business-to-business (B2B) meetings need to be encouraged and Mode-4 should be further liberalised to contribute to SME growth and create avenues for active GVC participation. A key impetus need to be given to public diplomacy as an instrument for “social connect” thereby encouraging people-to-people interactions. It is imperative that the two countries maintain a continuity in strategic and defence cooperation to keep leveraging mutual geo-economic benefits.

The writer is an associate professor and chair of the international business area at FORE School of Management, New Delhi. Views are personal.

Advertisement