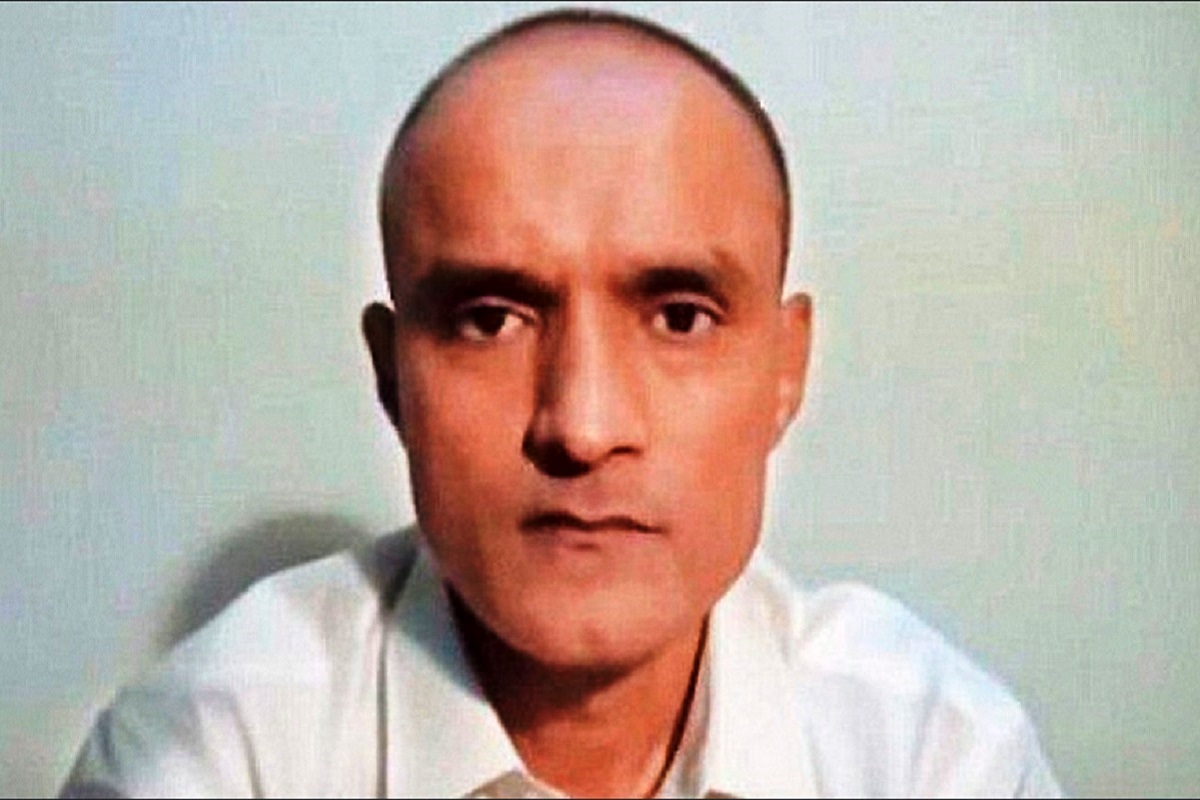

As the former Indian navy commander, Kulbhushan Sudhir Jadhav, continues to languish in Pakistan, there are no winners or losers in Wednesday’s verdict of the International Court of Justice at The Hague. The ha-ha to the west of the Radcliffe Line is, therefore, misplaced though the euphoria is specifically over the ruling that Jadhav’s detention will continue.

There is a pregnant message though in the court’s directive, ordering Pakistan to review the death penalty awarded in 2017. This is a reflection too on the conduct of the military courts and their rough-and-ready justice. The order, significantly enough, has been couched in the caveat that the government in Islamabad had violated India’s right to consular access. By that token, the Pakistan foreign office has suffered a diplomatic setback.

Advertisement

Hence the observation of the Bench ~ “The Court, by a vote of 15-1, has upheld India’s claim that Pakistan is in egregious violation of the Vienna Convention of Consular Relations, 1963, on several counts.” Well might Prime Minister Narendra Modi greet the ICJ order with the tweet that “Truth and justice have prevailed. I am sure Kulbhushan Jadhav will get justice.”

The case boils down to the cry for freedom. This is the critical issue on which, going by India’s perspective, there has been no headway quite yet. On closer reflection, it is on the bedrock of release that India’s efforts have floundered. The ICJ has refused to entertain India’s appeal to annul the decision of Pakistan’s military court and direct Islamabad to release Jadhav, and facilitate his safe passage to India. This is the equaliser that Pakistan has suffered with the order to review the death penalty. More accurately, both countries have countenanced a setback and in equal measure.

It would be pertinent to recall that India had urged ICJ to intervene in the case, submitting that Jadhav had been given an unfair trial and was denied diplomatic assistance.

Pakistan had argued that based on a bilateral treaty it was not obligated to allow diplomatic assistance for people suspected of being spies or terrorists. As it turned out, the court dismissed that argument and found by 15 votes to 1 (Pakistan’s vote) that Islamabad had breached Jadhav’s rights under the Vienna Convention on Consular Relations, by not allowing Indian diplomats to visit him in jail or assist him during his trial at a military court.

A glass panel had separated mother and son during a carefully choreographed interaction at the foreign office in Islamabad last year. The ICJ has indicted Pakistan’s treatment of the former naval commander, who was arrested in Balochistan in 2016 on charges of espionage.

While ICJ’s rulings are final and without appeal, it is unclear what exactly would constitute an effective review of Jadhav’s sentence. The judges have observed, however, that Islamabad will need to take all necessary measures, including changing its laws, to ensure that Jadhav’s case is properly reviewed. Meanwhile, he remains in prison, perhaps more sinned against than sinning.