Crisis Averted

The US Congress narrowly averted a government shutdown with the passage of a bipartisan funding bill, but the process laid bare the persistent challenges of governance in an era of heightened partisanship and external influences.

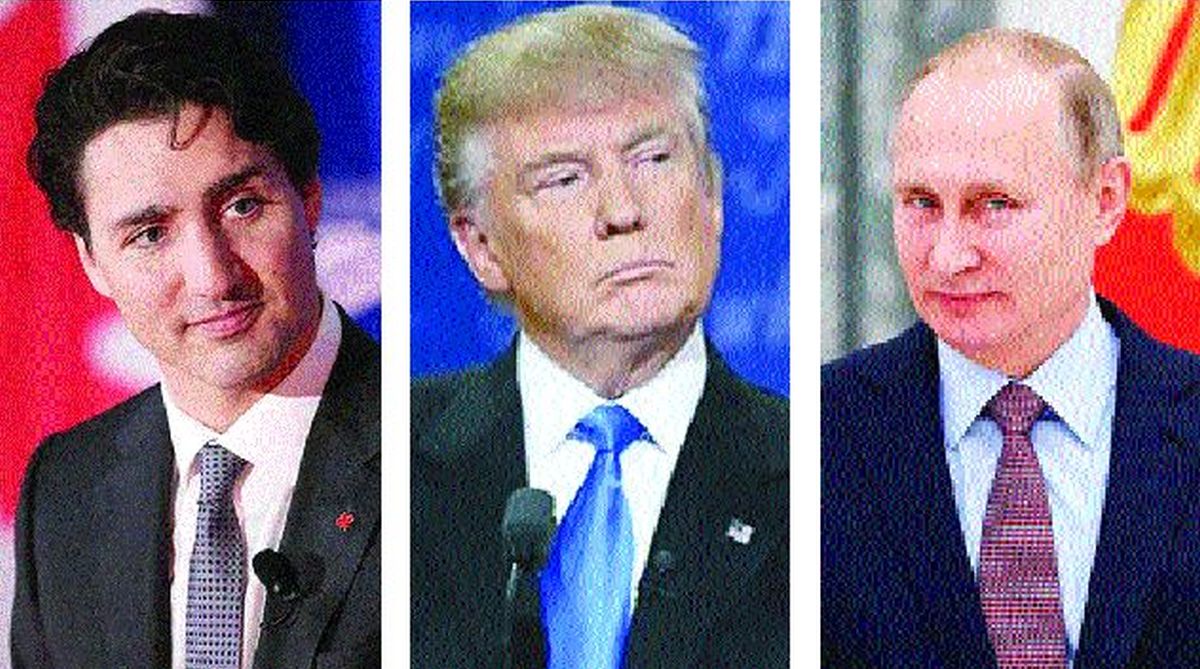

Prime Minister of Canada Justin Trudeau (Left) U.S. President Donald Trump (Center) Russian President Vladimir Putin (Right).

A seventeenth-century English satirist, Tom Brown, penned a doggerel about the Dean of Christ Church, one of the most prominent colleges, then as now, at Oxford. It went:

I do not like thee, Dr Fell

The reason why I cannot tell.

But this I know, and know

full well,

That I do not like thee, Dr Fell.

Advertisement

That pretty much sums up the sentiments, with rhyme but without reason, that the critics of President Donald Trump of the United States entertain towards him. In today’s deeply dichotomised America, a division that Mr Trump more than anyone else has helped create, one would have thought they would comprise the liberal left.

Advertisement

Initially, the redneck white Middle America, of the far-right, vehemently supported him with passionate fervour. They empathised with his pleas to “drain the swamp” of Washington’s “putrid” politics, or so it was thought, renegotiate America’s relationship with the world, and make the nation “great” again. The markets, and the overall economy, reacted extremely favourably.

In unconventional ways Mr Trump reached out to perceived adversaries: Mr Xi Jinping of China, Mr Kim Jong-un of North Korea, and Mr Vladimir Putin of Russia. For a while it seemed that the threats of a major conflict were averted. There must be a method in the behaviour-pattern, friends and foes alike concluded.

Alas, the early signs of success appear to be unravelling. The market and the economy are gearing to counter the trade war with China already unleashed. The early relationship with Mr Xi is deeply strained. There is obviously complete miscommunication with North Korea. Only the camaraderie with Putin appears to sustain, but a fruition of it could be the “kiss of death” for Mr Trump.

So, it may not be long that the left and right in America coalesce in the assessment of their new eccentric leader on the domestic front. The reason for their negative perception of Mr Trump, as opposed to the content of the doggerel cited earlier, is emerging in broader relief. In the world beyond, friends and foes alike are scrambling to develop a modus operandi vis-à-vis this new leadership in the White House.

This is necessary, as simply ignoring Mr Trump is not an option. America may no longer be a “city on a shining hill” to the rest of the world, but despite its reputation as a global leader far too damaged to be easily repaired, it still remains a power to be reckoned with. This will continue to be so, at least for some time to come. Its formal allies recognise this, but there is much truth in an observation of Mr Donald Tusk, Chairman of the European Union.

Bemoaning Mr Trump’s “capricious assertiveness” (as in unilaterally quitting the Iran nuclear deal, a decision that raised European heckles), Mr Tusk handed the US leader a left-handed compliment for ridding Europe of illusions (of American friendship), and quipped, with a tinge of exasperation: “with friends like this, who needs enemies?”

Likewise, Mr Trump’s adversaries must find him equally baffling. Mr Kim Jong-un of North Korea obviously relished the pomp and circumstance with which he met Mr Trump, the head of the world’s most powerful country, in Singapore on June 12. All the more so, because it transformed Mr Kim overnight into a world leader. Amidst much fanfare, he signed a document with his American counterpart, most carefully crafted to reflect his views as well.

Surely, the US State Department, doubtless containing some of the brightest diplomatic minds, would have accorded this all-important document most serious examination. Of the four significant points, a key third point was: Reaffirming the April 27, 2018 Panmunjom Declaration, the DPRK (North Korea) commits to work towards complete denuclearisation of the Korean Peninsula.

The sentence merits parsing. First, it was only a reaffirmation of what was already agreed between Mr Kim and President Moon Jae-in of South Korea just weeks earlier at Panmunjom. The language was not a product of the talks in Singapore. Second, it committed North Korea only “to work towards”, not accomplish, “denuclearisation”—which remained undefined—of the “Korean peninsula”, not dismantling of just North Korean nuclear capabilities. It did not contain anything that would require North Korea to give up its nuclear weapons unilaterally.

Indeed, it would have been surprising if North Koreans would agree to do so, readily, knowing full well it is the possession of such weapons on their part that brought the two sides together in Singapore in the first place. One must understand that if the North Koreans have the technological capacity to produce such weaponry, they would also be clued seriously into the nuclear deterrence theory that must have inspired them into such production. Simply stated, “deterrence” means that an inferior nuclear force could deter a more powerful adversary from attacking it, by the threat of an extremely destructive retaliatory response.

Key western proponents of the theory, Bernard Brodie and Thomas Schelling, broadly argued that such weapons, to be effective strategic tools, must always be on the ready though never actually used. It is probably true that the practice of deterrence by the US and the Soviet Union kept the peace throughout the Cold War.

So, a mathematically comparable equivalence of destructive powers led logically to a condition of stability. As a corollary, any erosion of such capabilities on one side would, by the same logic, create a “destabilising” situation, by enhancing the propensity of the other side to strike. Till such time, of course, the parties learnt to trust each other completely. As is the case between South Korea and America.

So, when Secretary of State Mike Pompeo travelled to Pyongyang recently, asking the North Koreans for “Complete Verifiable and Irreversible Dismantlement” (CVID)—which was always an American position but apparently not reflected in the Singapore Document – without offering an acceptable or comparable quid pro quo from the American side, the North Koreans, in their somewhat exaggerated linguistic predilections, termed the demands “gangster-like”.

Aware of the fates that Iraq and Libya have experienced in the past, and sensing that a change of American position can be a function of a single “tweet” from either Mr Trump or a successor, the North Koreans may have decided to have their faith in the leadership dialogue, but at the same time, keep their powder dry! Pyongyang wants what it calls a “phased and synchronous approach”. Obviously then, there is a major miscommunication.

All is not lost, of course, but we may be seeing the beginning of a negotiation that is bound to be long and arduous with no easy win for either side!

In the meantime, Mr Trump is headed to Europe for a NATO Summit. There are those who fear the recurrence of the sad events at the G-7 Summit in Canada prior to the Kim-Trump meeting in Singapore.

In much the same way, the NATO Summit will be followed by a meeting with Mr Vladimir Putin of Russia on July 16. At G-7, Mr Trump had demanded his economic allies give in to his tariff demands. At the NATO Summit, with regard to defence contributions from recalcitrant allies, Mr Trump, like Oliver Twist as in the tale of the parish boy by Charles Dickens (but with much greater clout), will ask “for more”.

The G-7 had ended in disarray, with Mr Trump calling his host and ally, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau of Canada, “weak and dishonest”. Doubtless, Mr Putin will wait eagerly, and with a modicum of curiosity, to hear Mr Trump’s assessment of his NATO “allies” before the Summit with his American “adversary”.

The writer is a former foreign adviser to the caretaker government of Bangladesh and is currently Principal Research Fellow at the Institute of South Asian Studies, National University of Singapore.

The Daily Star/ANN.

Advertisement