Himachal CM urges people to embrace teachings of Lord Buddha in daily life

Himachal Pradesh Chief Minister has called upon citizens to adopt the teachings of Lord Buddha in their daily lives to promote peace, compassion, and harmony in society.

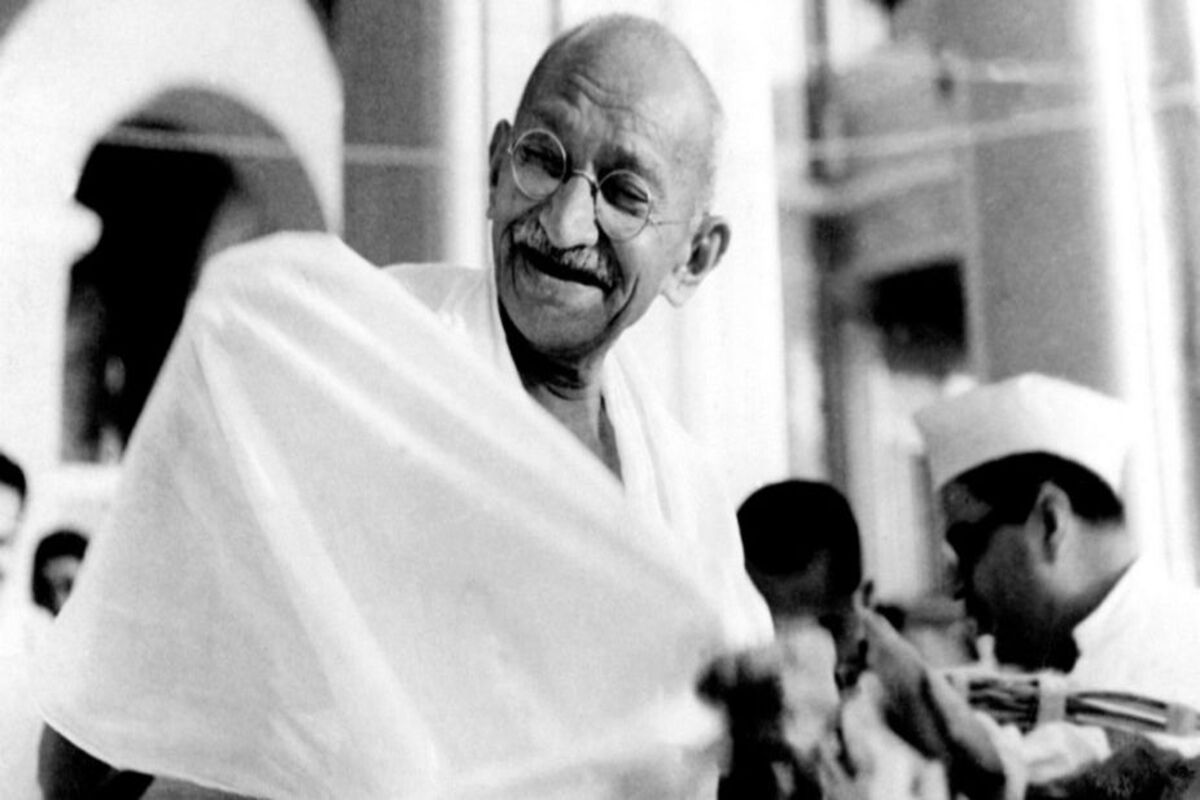

Gandhi envisioned a world that would evolve towards peace and harmony ~ a world where different religions, cultures and peoples of the world would live together with mutual respect and tolerance, rather than in suspicion and animosity. The lessons, gleaned from Gandhi‘s life offer us invaluable advice on leading an enlightened life ~ a more meaningful, self-aware, socially responsible and saner life

JAYDEV JANA | Kolkata | October 2, 2021 7:29 pm

Gandhi seems to stand alone among social and political thinkers in his firm rejection of the rigid dichotomy between means and end. The customary dichotomy between means and end originates in and reinforces the view that they are two entirely different categories of action. But to Gandhi, they are intimately and inextricably connected and “there is no wall of separation between means and end”. He compared the means to seeds and the end to a tree and stated: “There is just the same inviable connection between the means and the end as there is between the seed and the tree.” He was convinced that ultimate progress towards the goal would be in exact proportion to the purity of our means.

For Gandhi, the litmus test of any proposed action vis-à-vis any development planning is how it would affect the most vulnerable individual imaginable. The test is predominantly human and secondarily ideological. Political ideologists such as Lenin, Mao Zedong and Stalin were always willing to sacrifice people to policy. “A single death is a tragedy, a million deaths is a statistic,” Stalin famously declared in defense of ideologically driven war. On the contrary, Gandhi never considered his actions / policies in terms of statistics ~ they all bore a human expression. To an unidentified correspondent who had expressed uncertainty about which action to take in a difficult situation, Gandhi gave a wonderful talisman: “Whenever you are in doubt, or when the self becomes too much with you, apply the following test. Recall the face of the poorest and the weakest man whom you may have seen, and ask yourself if the step you contemplate is going to be of any use to him. Will he gain anything by it? Will it retore him control over his own life and destiny? In other words, will it lead to Swaraj for the hungry and spiritually starving millions? Then you will find your doubt melting away.”

Advertisement

Gandhi believed in the proverb, ‘Waste not, want not.’ He would not waste even paper. For example, he did not throw away paper only one side of which was written on. He used the other side too. He would turn used envelopes inside and write on them. In the dining room of his Sevagram Ashram there was a board bearing an appeal, “I hope all will regard the property of the Ashram as belonging to themselves and the poorest of the poor. Even salt shall not be allowed to be served in excess of one’s needs. Water may not be wasted.” Once he had misplaced his handkerchief. He along with others searched for it in vain. Another handkerchief was offered to him to save him the trouble as he had to hurry to a meeting. But he did not take that handkerchief. At night when he put away his shawl, he found the truant handkerchief pinned to it with a safety pin. Indeed, he was a passionate champion of a life based on three cardinal principles ~ simplicity, slowness and smallness.

Advertisement

In the words of E F Schumacher, “The cardinal error of our whole industrial way of life is the way in which we continue to treat irreplaceable natural capita as income.” The present environmental mess, ranging from deforestation and loss of biodiversity to pollution and change in the chemistry of the air is due to our unsustainable lifestyle. We can hardly afford to forget his prophetic statement: “Earth provides enough to satisfy every man’s need, but not for every man’s greed.”

Towards the end of his Autobiography ~ My Experiments with Truth ~ Gandhi says, “My devotion to truth had drawn me into politics and I can say, without the slightest hesitation and yet in all humility, that those who say that religion has nothing to do with politics do not know what religion means.” It was his “devotion to truth” which had drawn him into politics, not the ordinary politician’s love of power or wealth or authority. Gandhi always resisted power politics and realized that politics today encircles us like the coils of a snake from which one can hardly get out.

According to him, the only way of wrestling with snake is to introduce religion into politics. Politics was to him not a profession but a vocation. He himself claimed that the politician in him had not sacrificed any principle to gain political advantage. In the same manner, Gandhi believed that the heart, and not reason, is the seat of morality. His morality was not denial of politics. He wrote: “I feel that political work must be looked upon in terms of social and moral progress.”

Gandhi was extremely frugal and kept careful watch on how he spent every paisa. Of all public funds which he collected during his various movements, he had kept meticulous accounts. He used to say: “If we do not account for every single pie we receive and do not make judicious use of the funds, we shall deserve to be blotted out of public life.”

Gandhi was very keen on punctuality and took all his engagements seriously and kept to the minute. He was the most punctual man in India. His legendary punctuality had a utilitarian imperative ~ without it he would not have been able to answer the sacks of letters he got and to meet the streams of visitors who demanded his attention each day.

The Hindu masses practiced untouchability as part of their caste obligations. Gandhi’s concern and compassion for the Harijans dates to his boyhood. In his Autobiography, he recounted that although he had been a very dutiful and obedient child when it came to respecting his parents, he often had tussles with them when they asked him to perform ablutions after accidently touching Ukra, a scavenger boy who used to come to his house to clean up the yard.

When he returned to India from South Africa, he brought with him an untouchable boy named Naikar. He also adopted an untouchable girl, Lakshmi, as his own daughter and allowed a lower-caste family to stay in his Ashram. He risked unpopularity, ostracism, serious damage to reputation, and even death. Gandhi embarked on a countrywide tour, covering 12,500 miles and lasting for nine months and exhorted his countrymen to ease the blot of ‘untouchability’. Though he could not completely abolish the practice of untouchability, he nevertheless made a huge dent in the century-old custom.

Gandhi envisioned a world that would evolve towards peace and harmony ~ a world where different religions, cultures and peoples of the world would live together with mutual respect and tolerance, rather than in suspicion and animosity. The lessons, gleaned from Gandhi’s life offer us invaluable advice on leading an enlightened life ~ a more meaningful, self-aware, socially responsible and saner life.

(Concluded)

Advertisement

Himachal Pradesh Chief Minister has called upon citizens to adopt the teachings of Lord Buddha in their daily lives to promote peace, compassion, and harmony in society.

Former Chief Minister Ashok Gehlot, Leader of the Opposition (LoP) in the Rajasthan Assembly, Tika Ram Jully; party state president Govind Singh Dotasara, several MPs, MLAs, and senior party functionaries participated in the dharna and demonstration near the ED office at the Ambedkar (High Court) Circle here.

We all know that failure of the Cripps Mission to offer any advance towards self rule and growing discontent among the people were the immediate factors leading to the Quit India Movement in 1942. But, there was a story behind the story.

Advertisement