Discussed regional security imperatives, state-sponsored terrorism: Abhishek

The all-party delegation of MPs of which Diamond Harbour MP Abhishek Banerjee is part of paid tributes to the statue of Mahatma Gandhi today.

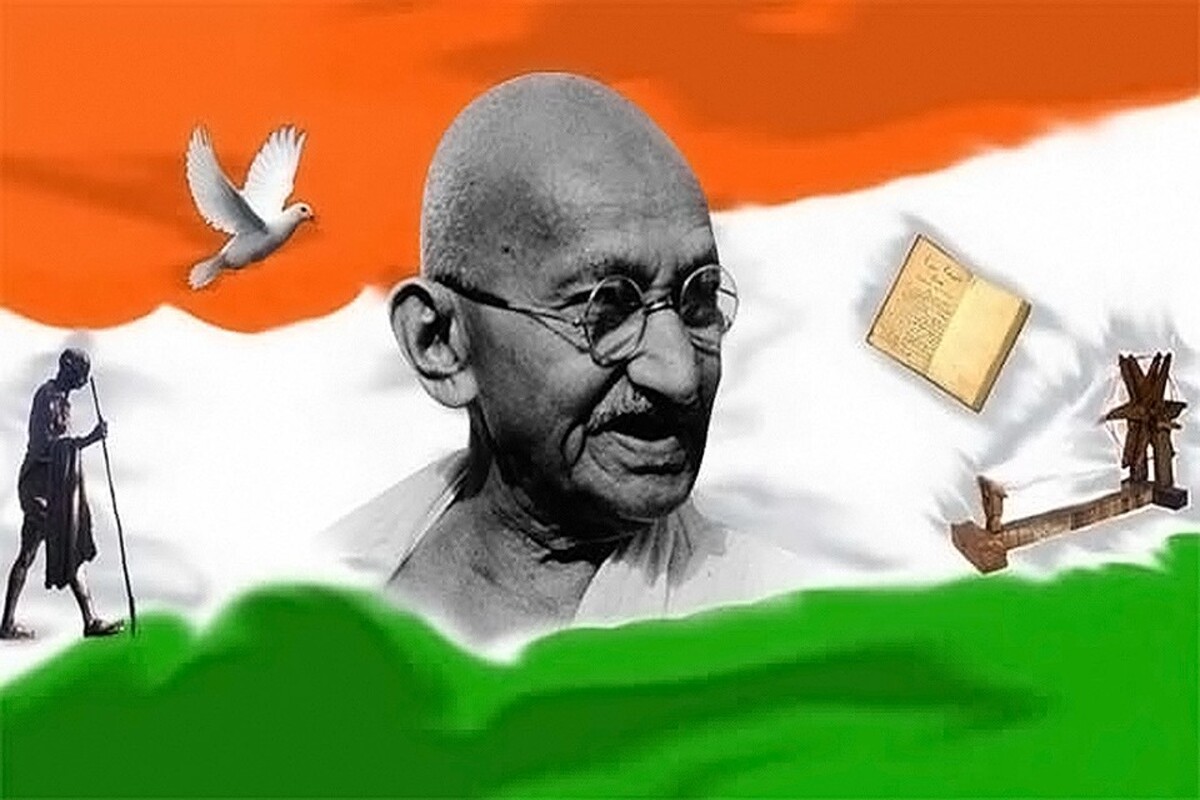

Surprisingly, it is easy to believe in the miracles of sainthood, but very hard to believe in those of flesh and blood; the prodigies of leadership who transform the world and the way we see and move and act in the world. Yet, as Gandhi himself taught, these are not miracles at all. He summed up the philosophy of his own epic life in five words: ‘My life is my message‘

Jaydev Jana | Kolkata | October 1, 2021 8:51 pm

‘So long as my faith burns bright, as I hope it will even if I stand alone, I shall be alive in the grave and what is more speaking from it.’

– Mahatma Gandhi, a week before India won freedom.

In major polls conducted by Time magazine at the end of the last millennium, Albert Einstein was rated as the Man of the 20th century and Mahatma Gandhi as joint runner-up with Franklin D. Roosevelt, the 32nd US President. Einstein held Mahatma Gandhi in the highest esteem; and regarded him as one of the greatest moral leaders of all time and also as ‘the miracle of a man.’

On the occasion of his seventieth birthday in 1939, he wrote: “Generations to come, it may be, will scarce believe that such a one as this (Gandhi) ever in flesh and blood walked upon the earth.”

Advertisement

Surprisingly, it is easy to believe in the miracles of sainthood, but very hard to believe in those of flesh and blood; the prodigies of leadership who transform the world and the way we see and move and act in the world.

Yet, as Gandhi himself taught, these are not miracles at all. He summed up the philosophy of his own epic life in merely five words: “My life is my message.” He lived his life seeking truth and wisdom and like Plato, he cared for the “the greatest improvement of soul.”

Advertisement

His life offered us vital lessons on living a meaningful, purpose-driven and morally awake life. In studying his life, a very clear set of principles, ideas and convictions emerge. Those are the sine qua non for any people, any nation or any enterprise, not to achieve the supernatural or merely to survive, but to evolve, to grow, and to prosper.

Gandhi was a practical idealist. He never did or said anything that he had not practiced, he also never expected another person to do anything he did not believe in. He used to say categorically, “What you do not get from my conduct, you will never get from my words.”

He went one step further and suggested, “As a matter of fact, my writings should be cremated with my body.” This does not mean, however, that his writings are not to be carefully examined. He wanted his writings to be taken seriously, but what he meant was that he could be best judged or understood by his conduct rather than his writings; and if some contradictions or inconsistencies appeared in his writings, they should be resolved in the light of his practices. Gandhi himself says, “To understand what I say one needs to understand my conduct.”

The essence of the teachings of Gandhi is fearlessness and truth and actions allied to these, always keeping the welfare of the masses in view. Gandhi had in his life many occasions for fear. Most men would have lost their nerve but he faced the situations calmly. Because, freedom from fear was usual with him. He also firmly believed that God would protect him as long as He needed him for His work. His greatest contribution was inculcation of fearlessness (Abhay) in the minds of Indian people who were demoralized after 200 years of colonialism, by a pervasive, oppressing, strangling fear, fear of being deprived of reputation and dignity, fear of the army, the police, fear of the landlord’s agents and fear of unemployment and starvation, which were always on the threshold. “Don’t be afraid” was the magic of his message. In the words of Pandit Nehru: “Whether there was something in the atmosphere or magic in Gandhi’s voice, I do not know. Anyhow, this very simple thing, ‘Don’t be afraid’, when he put it that way it caught on and we realized, with a tremendous lifting of hearts, that there was nothing to fear. Even the poor peasant straightened his back a little and began to look people in the face and there was a ray of hope in his sunken eyes. In effect, a magical change had come over India.”

Ahimsa, like truth, is as old as the hills. In his autobiography, Gandhi argued that the search for the truth is in vain unless it is founded on ahimsa.

However, he extended the meaning of ahimsa beyond non-killing or even non-injury and successfully promoted its principle to all spheres of life. As to the power of ahimsa, Gandhi said: “True ahimsa would wear a smile even on death bed brought by an assailant. It is only with that ahimsa we can befriend our opponents and win their love.” While ahimsa begets no violence, hatred and ill-will, violence begets more violence. In the words of Gandhi, “Eye for an eye makes the world blind.”

Truthfulness seemed to be inherent in Gandhi. From first to last, Satya or Truth, was sacred to him ~ the supreme value in ethics, politics and religion, the ultimate source of authority and of appeal.

He regarded it as a ‘philosopher’s stone’, the sole talisman available to mortal man. For his ceaseless pursuit of Truth, he had to pay a heavy price: deep mental anguish, political persecution, physical hardship and the denial of personal liberty, time and again.

But he persisted in his adherence to Truth in the face of tremendous odds. For he believed that in the end truth would assert itself. “His concept of satya, with ahimsa as the means, determined his doctrine of Satyagraha or active resistance to the authority, while the concept of ahimsa, with satya as the common end, enabled him to formulate his doctrine of Sarvodaya or non-violent socialism” [Raghavan Iyar]. No wonder, Gandhi’s example in steadfast adherence to Truth had led the country to adopt as its motto: Satyameva Jayate ~ Truth Will Ever Triumph.

Flailing state syndrome prevails in the planning process of India. Discussion of the planning process reminds us of a story of a drunkard. Once a drunkard lost the key of his apartment at night and kept searching for it near the street light for quite a while, when a second drunkard appeared on the scene to help him.

After joining the search, he asked: “Are you sure that you have lost your key here?” The first answered: “Not at all. But as there is light here, hence it is easier to search!” Just as the drunkard justified his search in the lit area forgetting about the rest of the street, planners/policy makers of our country justify their pronouncement by highlighting a narrow set of issues and forget the larger picture.

(To Be Concluded)

Advertisement

The all-party delegation of MPs of which Diamond Harbour MP Abhishek Banerjee is part of paid tributes to the statue of Mahatma Gandhi today.

Members of the all-party delegation led by Janata Dal (United) MP Sanjay Kumar Jha began their visit to Japan by paying floral tributes to Mahatma Gandhi in Edogawa, Tokyo.

Congress president Mallikarjun Kharge on Tuesday accused the BJP and RSS of conspiring to portray that Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel and Jawaharlal Nehru were against each other.

Advertisement