When sedition charges were clamped down on students raising anti-India slogans on the JNU campus, many wanted an end to sedition laws which they thought were an instrument used for suppressing free speech. After the British era, it was revalidated by the imposition of new grounds of curbing free speech under the Nehru Government.

The Nehru government through the First Amendment to the Constitution widened the scope of restrictions on fundamental rights ‘in the interest of security of the state’. The existing restriction on the ground of undermining the state or overthrowing the state was more specific and limited in its connotation. The new grounds, in a way, therefore, legitimised punishment for actions which were also punishable under sedition law. What was the pressing need for regulating free speech in such a way?

Advertisement

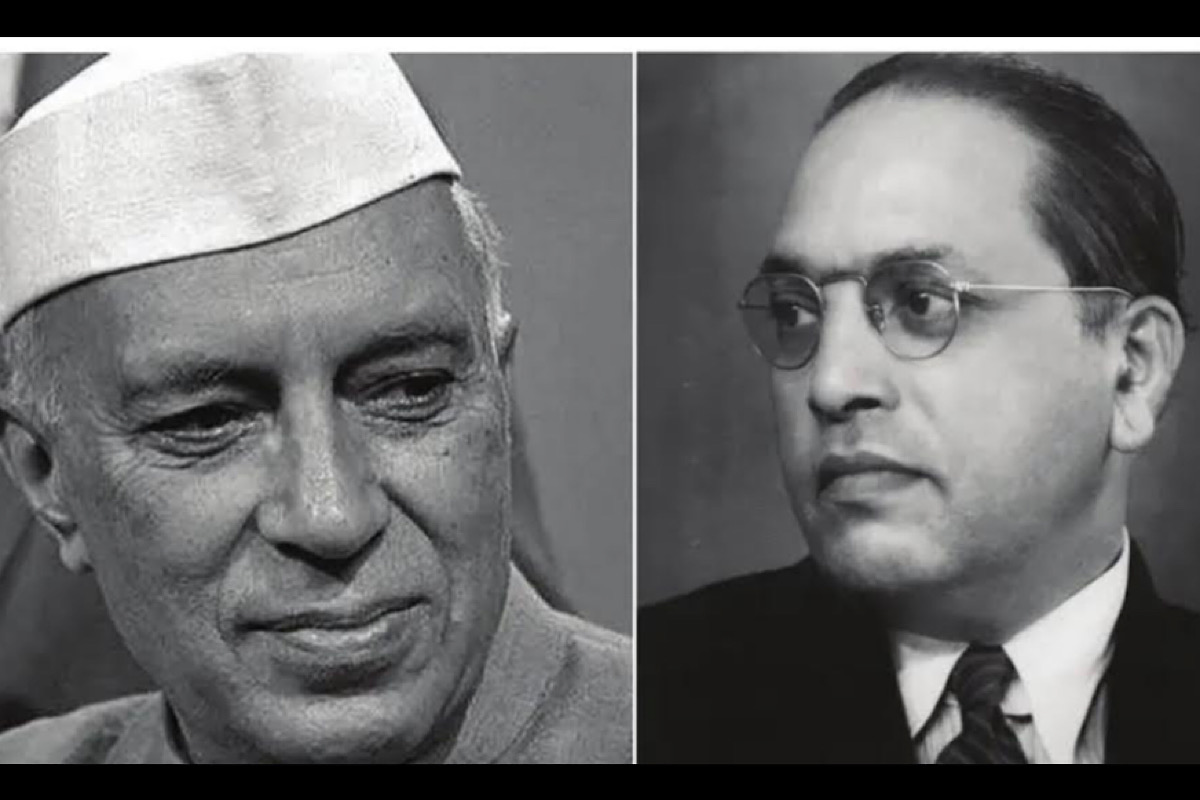

Nehru put forward 0bizarre logic for it. Speaking in Parliament, he pointed out, “we live at a time of grave danger in the world … at this moment when great countries… think of a struggle for survival …all of us have to think in terms of survival.” He did not disclose what these grave dangers were. Did he really mean that imposition of further restrictions on the fundamental right to freedom of speech and expression would help us survive? One wonders. Pilloried by the opposition in the Parliament, the government sought the help of Law minister B R Amedkar to defend its intentions with regard to the new restrictions on Fundamental Rights. Dr Ambedkar pointed out that the court in India always resisted introduction of the doctrine of ‘inherent police powers’. The doctrine was in force in the US. It gave the state an inherent right to regulate, in public interest especially, to protect the security of the state.

Such regulation may not be within the limits stated in the constitutional provisions. In other words, Ambedkar argued for empowering the government to impose restrictions on fundamental rights going beyond the limits enumerated in the constitution. For him, this was necessary because in India the apex court would not accept any limitation except what was specified in the Constitution. The same Ambedkar, in the Constituent Assembly, described Fundamental Rights as the very soul of the Constitution.

Amedkar’s defence of Nehruvian policy actually helped in revival of the spirit of the sedition law. It triggered fierce controversies over curtailment of fundamental rights in India. But, before we proceed further, the meaning of sedition has to be explained. Sedition law was inserted in the Indian Penal Code under British rule to suppress independence movements. Sedition means, ‘the use of words or actions that are intended to encourage people to be or act against a government’.

Section 124A of the Indian Penal code [IPC] lays down the punishment for sedition. Section 124A of IPC says, “whoever, by words, either spoken or written, excites or attempts to excite disaffection towards the government established by law in India shall be punished with imprisonment for life…” However, in one of the explanations appended to this section, it is stated that comments expressing disapproval of government’s policies to bring about changes by lawful means without exciting or attempting to excite hatred, contempt or disaffection, cannot be treated as an offence under this section. How do we distinguish between dissent by lawful means and seditious speeches?

Conflicting opinions often posed great difficulties in identifying the seditious content of utterances. It is one of the stumbling blocks in the process of taking punitive action against people inciting violent actions in their speeches. In many recent cases attempts were made to interpret violent speeches as mere criticisms of government policy.

These were based on blatant lies. It would be evident from a close examination of the notorious anti-India slogans raised in the Jawaharlal Nehru University campus in 2016. Some of the JNU slogans were: ‘Bharat ki barbadi tak jang rahegi’ [Battle will continue till India is ruined], ‘Afzal ke armano ko manzil tak le jayengi’ [Will take Afzal’s wishes to their consummation] and ‘Bharat tere tukre honge’ [India, you will be divided into pieces].

One must take note of the fact that Afzal Guru was a terrorist who masterminded the 2001 Parliament attack. The slogan that targeted the fulfillment of Afzal’s wishes [‘armano’] purportedly aimed at destruction of the temple of democracy in India. The slogans like ‘Bharat ki barbadi tak jang rahegi’ [Battle will continue till India is ruined’] or ‘Bharat tere tukre honge’ [India, you will be divided into pieces] are equally violent. If it is argued that Bharat ki barbadi actually meant the end of a poverty-stricken Bharat that sponsored discrimination, it would be a puerile defence of the most subversive comment.

Here, the difference between sedition and treason will be found relevant. Treason and sedition are often used interchangeably. But, there are differences between the two. Treason threatens the entire country while sedition is against the government established by law. JNU slogans aimed at the destruction of our nation. So, whatever might be the objection to sedition charges against students raising these slogans, no one can deny that such utterances were treasonous. They deserved punishment.

These anti-national outcries are not isolated incidents. They indicate that unlike Nehru’s vague ‘grave danger’ we are now confronted with a clear and present danger of a growing tendency to destabilise our nation. It helps realise a hostile neighbour’s long cherished dream. If we go on ignoring such developments, we will do it at our own peril.

(The writer is former Head of the department of Political Science, Presidency College, Kolkata)