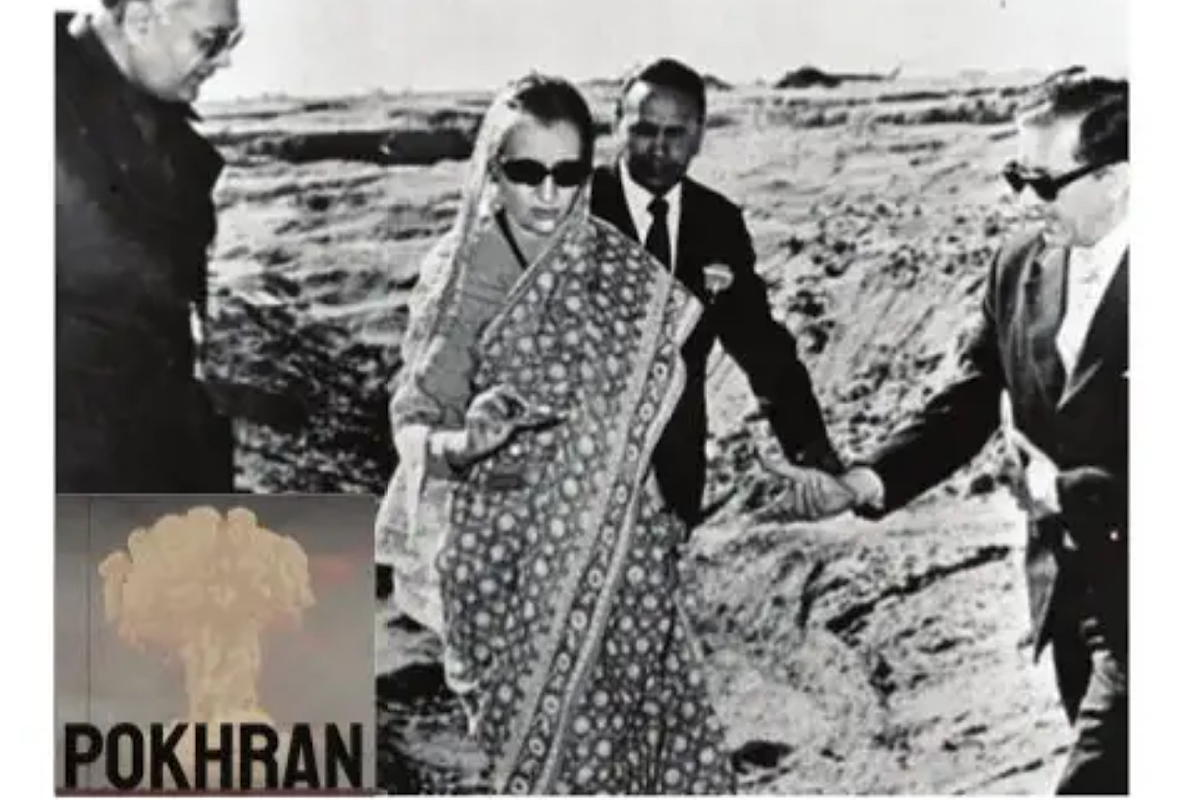

There was a sharp deterioration in India-Canada relations during the 1970s, following India’s ‘Peaceful’ underground nuclear explosion (PNE) conducted on 18 May 1974, in Pokhran (Pokhran-1). India-Canada co-operation for peaceful uses of nuclear energy began in the 1950s, when Canada agreed to build a 40 MW Research Reactor for India, known as the CIRUS (Canada-IndiaUS) reactor, in 1955. India promised that both the reactor and the related fissile materials would be used only for peaceful purposes.

Canada supplied half the initial uranium fuel for the reactor ~ while the US supplied the other half ~ and the heavy water for moderation. Both the US and Canada reacted negatively to the Pokhran1 nuclear explosion, with the latter blaming India for using nuclear materials from the reactors provided by Canada, although the Government of India asserted that no agreement with Canada had been violated, nor had any international agreement been violated, as India was not a signatory to the Non Proliferation Treaty (NPT), which New Delhi considered to be discriminatory. Canadian Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau ~ father of the current Prime Minister ~ wrote to then Prime Minister Indira Gandhi warning her of the consequences of developing nuclear weapons, while Foreign Minister Mitchell Sharp declared that trust between the two countries ‘was gone’. The Government of Canada, declared Sharp, “without dissent immediately suspended its nuclear cooperation with India” and all other forms of assistance, except food and fertilizer assistance and an agreement to roll over debt. India’s PNE and Canada’s response to it had dealt a severe blow to bilateral relations.

Advertisement

It is important to note, however, that Mitchell Sharp had announced the decision for ‘suspension’ of nuclear cooperation with India, not its ‘termination’, and a divided Canadian government did envisage the possibility of resumption of nuclear partnership with India and reconciling that with Ottawa’s commitment to non-proliferation. But Sharp’s successor in the Foreign Office, Allan MacEachen, supported by several of his Cabinet colleagues, nullified that possibility because of what they considered ‘duplicity’ on the part of India.

The 1974 nuclear explosion, and the imposition of Emergency by Indira Gandhi in the following year brought about a dramatic change in Canadian perceptions about India and led to a deliberate re-orientation in Canada’s foreign policy, with its foreign aid policy now focusing on Africa while the policy towards India and South Asia was marked by what Ashok Kapur called Canada’s own policy of, ‘benign neglect’ or indifference. New Delhi also downgraded Canada’s importance in its global policy perspectives, and became more concerned with developments nearer home: the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan and its ramifications for India, particularly in the context of the US decision to evict Soviet forces by arming Afghan Mujahideen. In this ‘Great Game’, Pakistan emerged as a ‘frontline state’ receiving substantial US economic and military assistance, that it was using to bolster its military strength against India, and sponsoring terrorist attacks on India. New Delhi, on its part , tried to forge closer ties with neighbouring states in South Asia through the development of regional cooperation, as envisaged in the SAARC.

During the 1980s, deep fissures developed in India-Canada bilateral ties over the activities of a section of Sikh immigrants who had migrated to Canada, in the wake of the development of the Khalistan movement that espoused a separate independent Sikh state of Khalistan comprising territories from the Indian State of Punjab, (and also from the Pakistani State of Punjab). Initially, the Khalistan movement was being funded by the Sikh diaspora in Canada (and the US), while Pakistan allegedly provided sanctuary and military training to the Sikh militants.But when the latter realised that maps of Khalistani organizations envisaged Lahore as the capital of the Khalistan state, Pakistan’s support petered out.

The violent Khalistan movement leading to the death of thousands of innocent people, followed by ‘Operation Blue Star’ to flush out terrorists from the Golden Temple in Amritsar; the suppression of pro-Khalistan activities by India; the assassination of Indira Gandhi by her Sikh bodyguards and the subsequent anti-Sikh riots in Delhi had a direct impact on IndiaCanada relations during the 1980s and beyond. These developments gave a spur to the anti-India activities of a section of Canada’s sizeable Sikh community. By the middle of the 1980s, their anti-India activities reached a new high as demonstrated by the bombing of Air India Flight 182 in 1985, en route to London from Montreal, by activists of the Babbar Khalsa group that resulted in the death of 329 people, including 268 Canadian citizens, mostly of Indian origin, and also some 24 Indian nationals and others.

Earlier in the decade, India had requested the extradition of Talwinder Singh Parmar, a leader of the Babbar Khalsa group who was subsequently identified as one of the principal conspirators behind Air India bombing, but that request was turned down by Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau. This and the tardy handling of the attack investigation by Canadian authorities were severely criticised in India, and by the families of the victims in Canada and India. Activities of the Pro-Khalistan elements in Canada thus became the principal obstacle to the development of friendly relations between India and Canada, replacing the nuclear issue. However, in a bid to develop cooperation for containing terrorism then Prime Ministers Rajiv Gandhi and Martin Brian Mulroney met in November 1985 and a bilateral extradition treaty was signed in 1987.

This was followed by the Agreement to set up a Joint Working Group on Counter-Terrorism, a decade later, in 1997, to coordinate policies against the Khalistan separatist groups. The Mulroney years (1984- 1993) did see some improvements in Canada-India relations, but there was no revival of the India-Canada ‘special relationship’, despite their cooperation in ending racism in Rhodesia and South Africa; nor did the extradition treaty expedite the process of extradition, as only six fugitives were returned to India between 2002 and 2020 because of the lengthy paper work and strong lobbying by the separatists. It was the policy of economic reforms in India initiated by Dr. Manmohan Singh, who was Finance Minister in P V Narasimha Rao’s Cabinet, that brought about fresh hope for improvements in India-Canada relations during the 1990s, especially after the Liberal Party came to power in Canada in 1993 in a landslide victory.

The new government viewed India as an attractive destination for trade, investment and economic cooperation and in October 1994, a major trade mission came to India under the leadership of Roy MacLaren, the Minister for International Trade. A document, ‘Focus India’, prepared the ground for the revival of India-Canada relations and this was followed by the visit of Prime Minister Jean Chretien to India in January 1996 ~ the first Prime Minister to visit India in 25 years ~ accompanied by a large team comprising several provincial ministers, two Cabinet ministers of the federal government, and business persons from 204 companies.

That the main thrust of the visit was on revival of economic cooperation could be seen from the fact that 75 commercial agreements worth $3.4 billion were signed. Prime Minister Chretien declared: “Canada is back in India and we are here to stay.” However, the euphoria was short-lived as Indians did not appreciate the visiting Prime Minister’s demand, while in India, that India should give up the nuclear option, nor his criticism of India’s child labour policies. A follow up visit by the Governor General of Canada in January 1998 failed to generate any reciprocal diplomatic visits from India. But it was the nuclear issue again that caused further setbacks to Canada-India relations, particularly because of the evangelical approach of Canada’s Foreign Minister Lloyd Axworthy (January 1996-Septembor 2000) whose pursuit of the doctrine of ‘human security’ was causing damage even to Canada’s own interests. Nor was his policy always consistent, as demonstrated by Canada’s participation in the Kosovo air war, under the pretext of ‘the end justifying the means’. So far as India’s tests (Pokhran-II) were concerned, these were criticised not merely by the P-5 states, but also by others.

No state, however, reacted to it as strongly as Canada did. The US also had criticised India and imposed economic sanctions (virtually mandatory under US law), and a ban on dual-use technology transfer. It was this, more than the economic sanctions, that hit India hard; but the US also kept the option open to start negotiations with New Delhi to be able to influence Indian policy, and it was with this end in view that the Strobe Talbot-Jaswant Singh negotiations began in July 1998 and continued till January 1999. What facilitated these negotiations were India’s unilateral declaration of a moratorium on further tests, its pledge not to use nuclear weapons against a non-nuclear weapon state, and the declaration that India would not be the first state to use nuclear weapons against a nucleararmed adversary. Perhaps equally important was the role of the Indo-American community, the wealthiest demographic group in the US, in transforming the image of India within the US Congress. But Axworthy refused to take note of India’s postPokhran declarations. Canada recalled its High Commissioner in New Delhi, cancelled Canadian International Development Agency’s consultations regarding $54.5 million of non-humanitarian assistance over five years, suspended talks on the expansion of trade and banned all military exports to India.

Banning of military exports to India was not unexpected; but Axworthy did not stop here. He opposed non-humanitarian assistance to India by the World Bank and announced that Ottawa would oppose New Delhi’s attempts to secure permanent membership of the UN Security Council. Canada took the lead in diplomatically isolating India in G-8 and other international fora. India-Canada relations reached a new low because of Axworthy’s evangelical policies; Ottawa lost the opportunity to influence India’s evolving nuclear doctrine, and of improvements in India-Canada relations.

Preston Manning, leader of the Opposition Reform Party, though critical of India’s nuclear explosions, called for withdrawal of economic sanctions against India and urged the Canadian government to invite Prime Minster Vajpayee to visit Canada so that he could explain the reasons for conducting the nuclear tests. Since his comments were made while he was visiting New Delhi, these were not given much importance and were viewed as an attempt to win the hearts of the traditionally pro-Liberal Indo -Canadian community.

(The writer is Professor (retired) of International Relations and a former Dean, Faculty of Arts, Jadavpur University)