On 19 January 1969, a 20-year old Czechoslovakian student, Jan Palach, staged a solitary protest at Prague’s Wenceslas Square by dousing petrol and setting himself on fire.

The protest was against the return of Soviet-supported Czechoslovakian authoritarian rule following the brutal ouster of Alexander Dubcek (1921-92). The latter had promised ‘socialism with a humane face’, also known as the Prague Spring in the autumn of 1968.

Advertisement

Palach passionately wanted a return of freedom and democracy which in practical terms meant the end of all kinds of censorship and resignation of politicians who enjoyed illegitimate power bereft of popular support.

Before the student rebellion started in May 1968 in Paris, the Czech students led by Vaclav Havel (1936-2011) demanded elementary civil and political rights like freedom of speech and assembly.

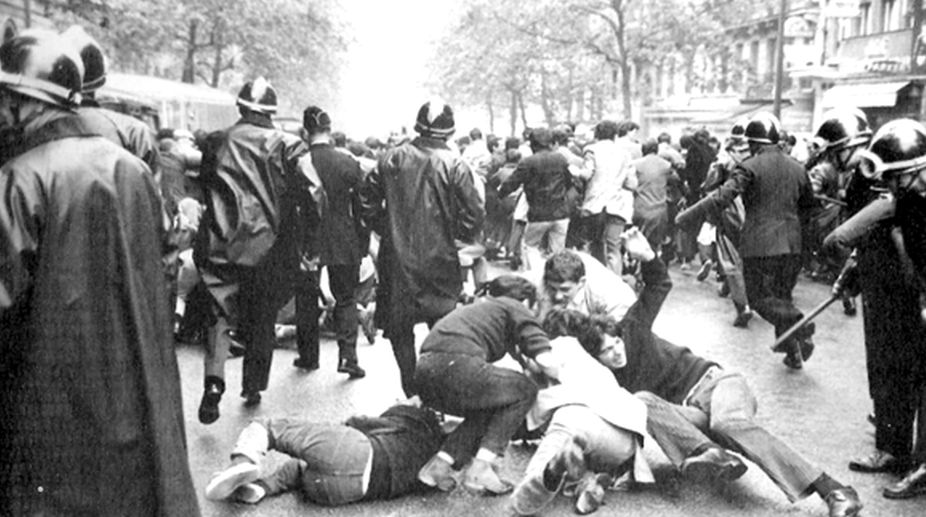

The protest against such suppression in Prague, as Anne McElvy has remarked, was more significant an event to remember than what happened in Paris in May 1968.

She lamented that the Czech protest was pushed to the margins. The leaders of the Paris rebellion even today insist, like Daniel Cohen Bendit or Dany the Red did then, that they were scripting history and that they had developed “an exalted feeling” as they “had become agents in world history”.

There was a pronounced emphasis on the power of imagination with certain broadly conceived new categories of conflict such as the ancient versus the youth, the system versus the movement, hero versus villain, power against counter-power, substituting an undefined anarchic order.

The rebellion was over within a month. Instead of becoming agents of change in terms of world history, many of them became part of the establishment. For instance, Bendit became a member of the European Parliament.

The revolt in Paris followed the student revolts in the US and Germany in a big way. But initially in France, there were only a few symbolic protests against the Vietnam war. The 1968 events first broke out on the Nanterre Campus and then spread to Sorbonne.

The protest was initially against dormitory rules that prohibited male visitors to female dormitories. A wider rebellion was planned and related to the selection at entry-point for undergraduates. This did not take off.

A student at Nanterre Campus declared: “Equality of access to a university is a right’. It questioned the baccalauréat system that Napoleon had once devised . It allowed all those who passed to apply for any undergraduate course, regardless of their suitability.

By the time the occupation at Sorbonne began, the slogan was “be realistic, demand the impossible” which in itself demonstrated the ambiguity of the entire protest. This was in sharp contrast to the students’ upheavals in Poland, East Germany and Czechoslovakia. In these countries, they were clamouring for the realization of elementary civil, political and human rights.

The French revolt was a consequence of a highly centralized bureaucratic state and a stifling social order under de Gaulle. Dany the Red explained the students’ revolt in France with reference to liberalization and democratization that received an impetus after World War II.

In the context of a more organized and violent French exceptionalism, represented by Sorel and the other Syndicalists, the students were inspired to attempt a social revolution.

They were subsequently joined by a section of the working class leading to the occupation of factories in defiance of the Communist party, the PCF. It opposed the movement and the powerful trade union movement restricted by the aloofness of a labour aristocracy.

With a broad and vague critique of both capitalism and Communism, the French rebellion demanded enlargement of freedom in a personalised manner.

To that was added a philosophy of free love and sexual freedom without any serious underpinnings of how to usher in a new and more humane order.

André Malraux (1901-76), Jean Paul Sartre (1905-80), Allen Ginsberg (1926-97) and Tariq Ali personified that galaxy of luminaries who inspired and led the movement… besides Dany the Red.

There were a variety of ideological preferences from Trotskyism, to new left theories and even anarchism. The students’ movement did not demand greater democratization and opening channels for participatory democracy, but a social revolution that would change the face of the world.

The absence of details of what this change entailed was conspicuous. They did not provide a viable alternative to what they were challenging ~ a reasonably strong party system and well-established institutions that protected individual rights and enforced the rule of law, indeed the foundation of the modern political order.

The most important lesson of the Paris rebellion was what Eduard Bernstein had perceived in the late 1890s that the working class had become wealthier and wanted to advance its economic interests without breaking away from the present order.

Summing up the May 1968 Paris rebellion, Marcuse remarked in 1972 that it was “the immediate expression of opinion and will of the workers, farmers, neighbours”.

The French Communist Party (PCF) realised this as well as Lenin did in 1902. This prompted him to write What is to be Done. He introduced the Communist party as an entity in the vanguard of the proletarian revolution to replace the revolutionary proletariat that was intoxicated by economism.

De Gaulle called for a national election on 30 May 1968 by dissolving the National Assembly and securing a resounding victory in the June election. But surprisingly even after fifty years of a failed rebellion, 60 percent of the French population have a positive view of the event.

Hannah Arendt predicted that the children of the next century would learn about 1968 the way Arendt’s generation learnt about the 1848 revolutions in Western Europe.

Habermas also echoed the feeling positively in the German context. According to him, as a consequence of the events in France and Germany, society in Germany was liberalised. The diehard conservatives were compelled to change their views.

The rights of women and children were gradually acknowledged. Women started moving up the ladder enjoying leadership positions and even earlier taboos like same-sex marriage found increasing social and legal acceptance.

Cohen Bendit described the events of 1968 as the birth of multiculturalism, but sopped short of mentioning that by the end of the 20th century it ran out of steam. Theoretically Brian Barry demolished its arguments. Germany and Great Britain officially rejected it.

The Paris rebellion supported the national liberation movements but eulogised Mao Zedong, ignoring his atrocities. An interesting difference between Sartre and Camus also came to light.

Both supported the national liberation movement in Algeria. Sartre supported the nationalist liberation front ignoring its perversions while Camus, well aware of their shortcomings did not.

It is now generally recognized that the 1968 student rebellion did not begin in either Paris or Berlin. It began on the West Coast of the USA in Berkeley with massive protests against the Vietnam war championed by the leader of the free speech movement, Mario Savio (1942-96).

The evolution of counter-culture was championed by Woodstock, Bob Dylan and Joan Baez. They inspired the French students in May 1968 rebellion.

It remained a broad coalition of young students supported by some sections of young workers and those under 30 years of age without any detailed programme while the majority of people remained aloof.

The Communist Party’s (PCF) control of trade unions and workers continued after this momentary dislocation. Its opposition to the rebellion was realistic.

In contrast, the continued suppression and the sporadic protests continued throughout Poland, East Germany and Czechoslovakia till Communism ended not only in East Europe but even in the Soviet Union.

The Czech reformers and students, who demanded elementary rights, were on the right side of history, whereas their West European counterparts enjoyed only momentary glory. But they are still venerated by the Western radicals.

The writer is former Professor of Political Science, University of Delhi