US sues bankrupt crypto platform Voyager’s CEO, permanently bans company

The US Federal Trade Commission (FTC) has announced a settlement with bankrupt crypto company Voyager that will permanently ban it from handling consumers’ assets.

In India, when a bank fails, innocent depositors lose out, because deposits in banks are insured only up to Rs 5 lakh by the Deposit Insurance and Credit Guarantee Corporation, which means that one would get a maximum of Rs.5 lakh in case of bank failure, that too after many years. Statistically, only 51 per cent of the total bank deposit base is covered by insurance. Looking at the aftermath of recent bank failures, one finds that even after three and a half years, the assets of PMC Bank are yet to be liquidated; depositors initially got only Rs 1,000 per account, and a total of Rs 1 lakh till now

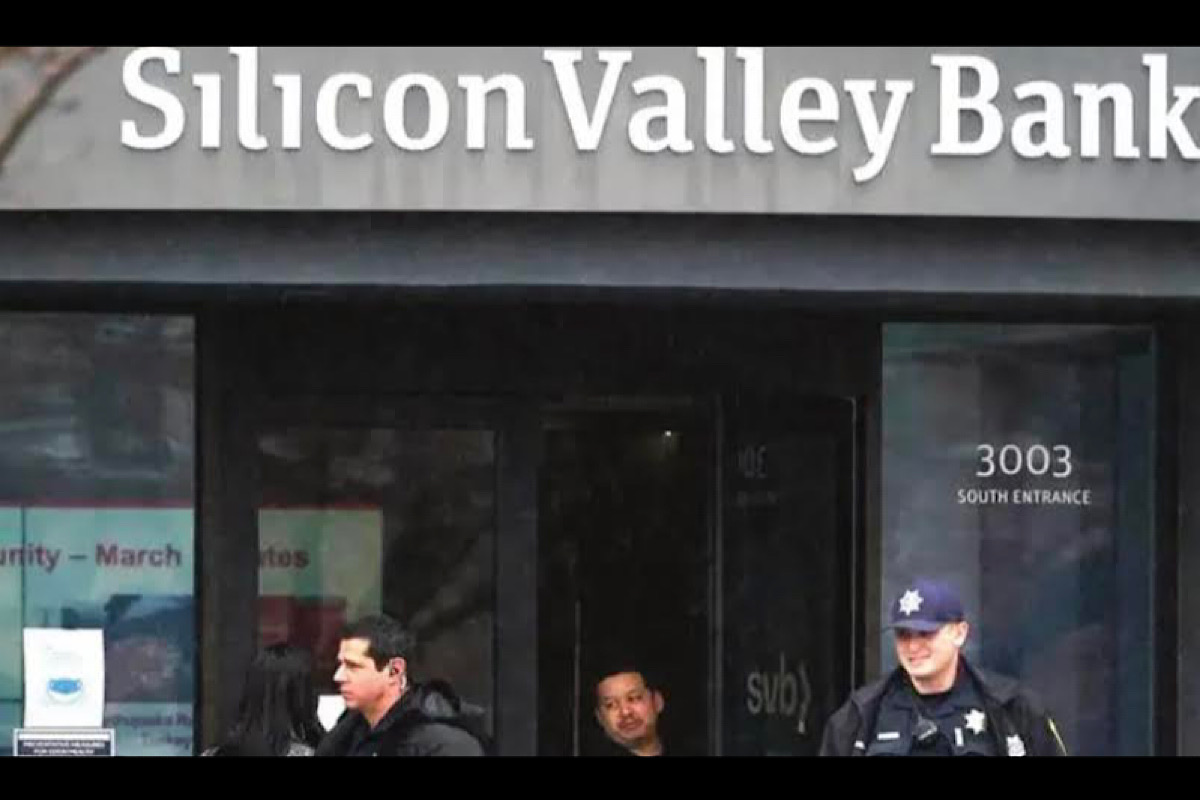

Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) [Photo: SNS]

The failure of Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) has generated a disproportionate amount of interest in India. Indian users of social media took perverse pleasure in the SVB failure ~ treating it as some kind of divine punishment for people of a nation connected with the Hindenburg Report.

Silicon Valley Bank has more than one bone to pick with social media; it is the first bank to have failed as a result of social media posts. To explain: Silicon Valley Bank was the 16th largest US bank, with deposits of US$220 billion, catering mainly to tech entrepreneurs of Silicon Valley, many of them of Indian origin. The run on Silicon Valley Bank started when prominent tech personalities and investors started speculating about the financial health of Silicon Valley Bank on Twitter, advising depositors to withdraw their money: the “SVB” thread had more than 200,000 tweets on a single day. Billionaire investor William Ackman of Hindenburg Report infamy tweeted on 11 March “Absent a systemwide @FDICgov deposit guarantee, more bank runs begin Monday am.” People reacted angrily when Vivek Ramaswamy, the Indian origin tech entrepreneur and presidential hopeful, advised caution.

Advertisement

After Silicon Valley Bank, social media turned its attention to regional banks and the hashtag #BankCrash started trending on Twitter. Consequently, shares of Silicon Valley Bank tanked by 60 per cent on 9 March, and shares of regional banks soon followed. Predictably, Silicon Valley Bank has deleted its Twitter account.

Advertisement

Regulators stopped trading in SVB shares on 10 March, and on 12 March, Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), stepped in and took control of SVB. Under law, FDIC guarantees only $250,000 per depositor, but within a day the Biden administration decided that all depositors should get back their deposits in full, including companies like Roku Inc. that had a balance of $487 million. Thus, the banking crisis was resolved; full protection for depositors restored the confidence of depositors in the banking system and there was no domino effect in Silicon Valley.

Soon thereafter, shares of regional banks regained their original levels. Explaining the bailout, President Biden stated that executives of Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank would lose their jobs, depositors will get their money in full, but investors will lose their shirt. However, for all his labours, Mr Biden has been criticised for favouring uninsured depositors, at the cost of bank shareholders and American taxpayers.

India is no stranger to bank failures; half of the fourteen private banks which were floated in 1993, 2003-04 and 2013-14, have bitten the dust, the last being Yes Bank. Public Sector Banks have done no better; in view of their escalating nonperforming assets (NPAs) and ballooning losses, Reserve Bank of India had placed 11 of the 21 public sector banks in Prompt Corrective Action (PCA) mode, in 2019. Public Sector Banks could regain their health only after a write-off of Rs 10.10 lakh crore.

In India, when a bank fails, innocent depositors lose out, because deposits in banks are insured only up to Rs.5 lakh by the Deposit Insurance and Credit Guarantee Corporation, which means that one would get a maximum of Rs 5 lakh in case of bank failure, that too after many years. Statistically, only 51 per cent of the total bank deposit base is covered by insurance. Looking at the aftermath of recent bank failures, one finds that even after three and a half years, the assets of PMC Bank are yet to be liquidated; depositors initially got only Rs1,000 per account, and a total of Rs.1 lakh till now.

Investors in Tier-1 capital of Yes Bank got nothing when the bank went kaput, and under the scheme of amalgamation approved by the Government, shareholders of Laxmi Vilas Bank have got nothing.

Contrast this with the US approach, the US Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, which handled 165 bank failures in 2008 and 2009 alone, guarantees bank deposits up to $2,50,000, and makes payments to depositors of failed banks, by the next business day. Also, in contrast to Silicon Valley Bank, which failed because Government Bonds held by it lost their value in consequence of rate hikes by US Fed, most banks in India failed because of motivated lending beyond the repaying capacity of borrowers ~ the creditworthiness of borrowers being overestimated for extraneous considerations. For example, banks overvalued the pledged assets of people like Nirav Modi and Mehul Choksi and extended credit to them, far exceeding their net worth. Further, banks failed to monitor the utilisation of the loaned funds. Contrast this with the treatment you or me, an ordinary middle-class person, would receive if we went to the bank for a small loan. In addition to mortgaging all our assets, we would be treated like Mallyas in the making. Should we default even on one instalment, we would find the bank’s strongmen at our doors. There are no means for a depositor or retail shareholder to know the ways in which their money is being put at risk by the shenanigans of the top management. For example, PMC Bank’s Annual Report dated 12 September 2019 did not give any indication that the Bank was stressed and was about to fail within the next two weeks.

Rather, the latest Balance Sheet, audited by a reputed firm of chartered accountants, showed a net profit of close to Rs 100 crore and Gross NPAs of only 3.76 per cent. Surprisingly, PMC’s fraudulent conduct was exposed not by auditors or regulators but by some public-spirited lady employees of the bank.

Similarly, rating agencies had given IL&FS the topmost rating which was amended to unsatisfactory only after IL&FS collapsed. No one came forward to take responsibility for the sickness of the 11 Public Sector Banks which had to be put under Prompt Corrective Action. Shifting blame, the RBI hastily clarified that it did not have much control over Public Sector Banks because the chief executives of PSBs were appointed by the Finance Ministry.

In most cases, it was found that a few non-performing loan accounts had brought a bank to its knees. Despite involvement of myriad enforcement agencies, defalcated moneys have never been recovered, which raises doubts on the motive behind the obsessive secrecy under which banks operate.

The ladies heading ICICI and Axis Bank, who at one time enjoyed iconic status, had to leave their jobs under a cloud; one of them was briefly arrested, and is still under investigation for doubtful dealings with a borrower. Repeated instances of massive bank frauds and bank failures have put a question mark over the capability of the Reserve Bank to oversee the working of banks.

The Narasimham Committee-II (1998) Report had recommended greater autonomy to public sector banks to enable them to be run professionally. Government equity in nationalized banks was proposed to be reduced to 33 per cent and the practice of nominating MPs, politicians and bureaucrats to bank boards was proposed to be discontinued because such persons were found to be interfering in the day-to-day operations of banks, often forcing the banks to lend to undeserving persons. Even after twenty-five years, none of these crucial reforms has been implemented.

All recommendations of the Banks Board Bureau, which was formed for recommending names for selection of heads of Public Sector Banks and Financial Institutions, were invariably junked. Proceeding on the premise that there is no inherent advantage in having a large number of very large banks, why can’t we have smaller banks that can be managed on commercial principles by their own directors? The directors of such banks should be finance professionals who would be well paid for their labours, and not random wellconnected individuals.

Smaller banks would not be able to hide their misdeeds in the plethora of figures in the manner the bigger banks do. Each bank branch would function as a profit centre with a mandatory annual audit, with commensurate rewards to staff for good performance. In this setup, poor performance and fraud would be quickly identified and corrected without sending the bank in ICU.

Moreover, to shore up confidence of the public in the banking system, instead of reviving failed banks by injecting capital from PSUs like SBI or LIC, the Government should pay back depositors fully and send the bankrupt banks to NCLT.

In the current scenario, the succinct observation of poet and playwright Bertolt Brecht definitely holds true: “It is easier to rob by setting up a bank than by holding up a bank clerk.”

(The writer is a retired Principal Chief Commissioner of Income-Tax)

Advertisement