In the lap of the mountains: Ishaan Khatter’s Kashmir pictures are an adventurer’s delight

Actor Ishaan Khatter, who was last seen in the period film ‘Pippa’, is currently enjoying his time in Kashmir.

Farooq Abdullah remained a mute spectator when, in his presence, the National Flag was dishonoured during the 1983 India-West Indies cricket match at Srinagar.

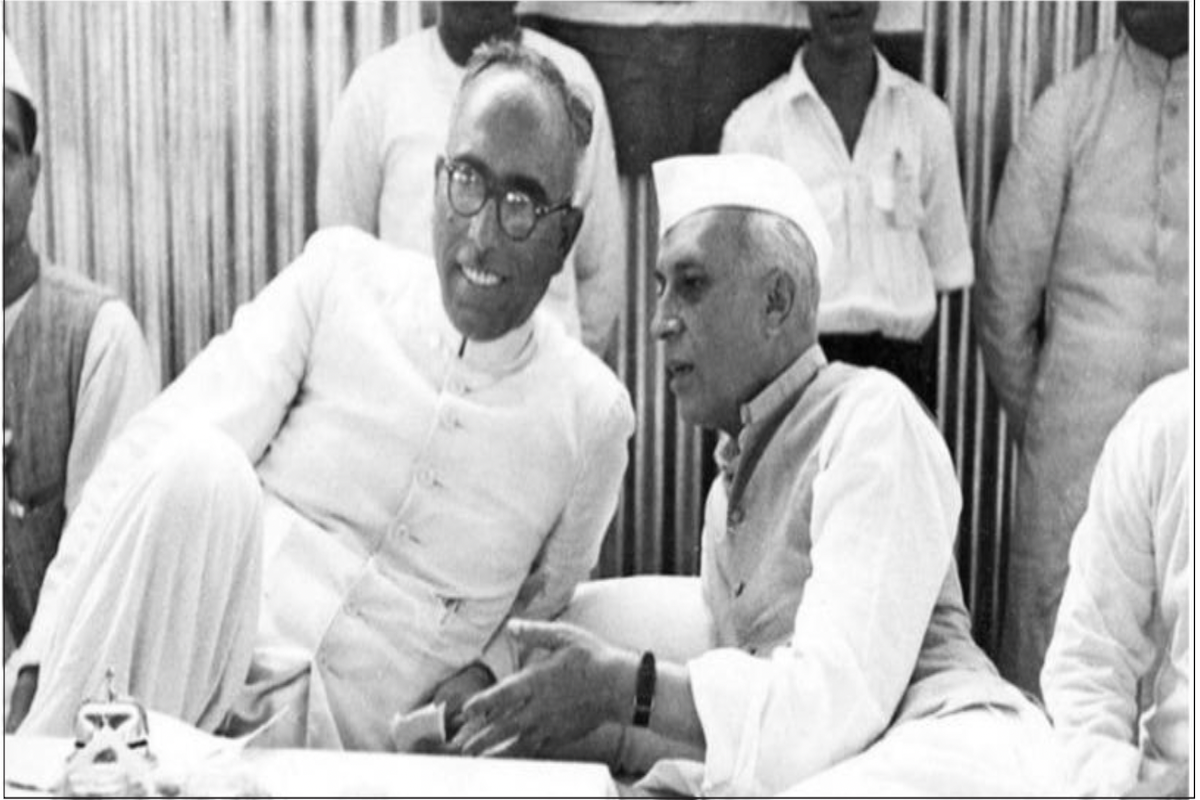

File photo

Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru lent support to Sheikh Abdullah, blindly trusting his secular democratic objectives. But gradually it was revealed that beneath the ideological grandstanding, Sheikh had an agenda related to his personal ambition to become the unchallenged ruler of the state. With this purpose in view, sometimes, he played the communal card and sometimes took recourse to change partners in national politics.

When Sheikh launched the “Quit Kashmir’’ movement in 1946 to turn the Maharaja into a mere constitutional head, he was arrested. Nehru stood by him. But as soon as Congress decided to work separately with its own organisations in the state, the Sheikh issued a ‘Fatwa’ that it would be a sin to offer the funeral prayer, “namaz-e-janaza”, for Muslim members of the Congress Party.

Advertisement

India’s victory in the Bangladesh war when Congress was in power at the centre changed Abdullah’s strategy. He came close to the Congress once again. The Indira-Sheikh Accord of 1975 allowed the Sheikh to re-enter Kashmir politics. He became the chief minister of Jammu and Kashmir and dropped his long-standing demands of Kashmir’s right to self-determination, toe- ing Indira’s line. But the bonhomie did not last long.

Advertisement

After Congress lost the Lok Sabha elections in 1977, Sheikh Abdullah came close to the Janata Party. Again, when Janata Party decided to fight the State Assembly elections on its own, he said, “Janata Party is anti-Mus- lim…” National Conference workers were instructed by the Sheikh to seek votes with Quran in hand. This double standard on secularism was Sheikh’s plan of enlisting the majority community’s support in the valley.

It is now evident that such political hypocrisy helped Pakistan sustain its efforts to incite insurgency in the State. Certain national political parties both in the government and in the opposition have also been insisting on making peace with the separatists and Pakistan-backed terrorists in the valley through dialogues. The way Pakistan has been launching its so-called Kashmir campaigns has to be brought to the fore to expose these enemies within. Pakistan never forgot how its plan of the annexation of Kashmir fell through in 1947. Eighteen years later, in 1965, it adopted strategies codenamed, ‘Operation Gibraltar’ and ‘Operation Grand slam’. ‘Operation Gibraltar’ was for sending armed militants to Kashmir for inciting revolt. This would be backed, if required, by ‘Operation Grand Slam’ ~ deploying Pakistani troops with a similar objective. In short, cross-border terrorism would be unleashed both by militants and the Army.

Pakistan’s infiltration, as ‘Operation Gibraltar’, was not only aimed at fomenting insurgency but also triggered complete Islamisation of the valley so that it could be incorporated in Pakistan on the ground of religious affinity. Minority baiting was integral to this diabolical scheme. Kashmir politics, despite its numerous ramifications, was drawn to these principal targets of Pakistan.

Generally, it is perceived that there are two major trends in the Kashmir insurgency: one supporting independence and another seeking union with Pakistan. But the situation is far more complicated than it seems on the surface level.

Jammu Kashmir Liberation Front [JKLF], one of the dominant insurgent groups, favoured Kashmir’s independence. As a result, Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence [ISI] backed the Hizbul Mujahideen, which wanted a union of Kashmir and Pakistan. However, an interview of JKLF leader Amanullah Khan reveals that in 1987, JKLF and ISI struck a deal with Pakistan’s President, General Zia, that JKLF would send militants across the line of control for ISI training and ISI would supply weapons and provide military instructions to JKLF. One year after this deal, on 31 July 1988, two bomb blasts in Srinagar triggered by JKLF marked the beginning of the Kashmir insurgency, also known as the Kashmiri version of the intifada.

But Kashmir was turbulent even before the Srinagar blast of 1988. In 1984, to unleash the anti- India campaign, Ravindra Mhatre, an Indian diplomat was killed in Birmingham by JKLF activists called Kashmir Liberation Army. The campaign be- came stronger when Maqbool Batt, a terrorist, was executed in Tihar Jail. The then President of India was informed by at least three Ministers that ‘secessionist forces’ were getting the official backing of Farooq Abdullah’s administration. This was not unusual for a man like Farooq Abdullah who was

rubbing shoulders with anti-national elements ever since he met JKLF leader Amanullah Khan in London in 1971.

Farooq remained a mute spectator when, in his presence, the National Flag was dishonoured in the 1983 India-West Indies cricket match at Srinagar. He unhesitatingly cashed in on anti-India sentiment as and when the separatists fomented it. Emboldened by his closeness to the separatists, the extremists took out processions shouting ‘Pakistan Zindabad’.

Farooq’s government fell when G M Shah broke away with a group of National Conference leaders. But Farooq became Chief Minister again when Rajiv Gandhi lent support to him by dismissing Shah’s government after the 1986 riots in South Kashmir. It is quite strange that one who, in 1983, had threatened a ‘blood bath if Congressmen did not behave’ received Congress’ support in 1986. Such political games did not remain confined to one dispensation in power at the Centre.

Militancy in Kashmir reached its height in 1989 when Home Minister, Mufti Mohammad Sayeed’s daughter was kidnapped with a demand for the release of certain terrorists. The Government of India buckled under pressure. In such a desperate situation, Jagmohan was appointed Governor of the state in January 1990 for the second time. In his first term, he had earned the reputation of handling terrorist activities with a firm hand. He was a strong and determined administrator. But the political leaders had something else in their minds.

Farooq Abdullah resigned, resenting Jagmohan’s appointment. The very next day, the exodus of Pandits began. The separatists started to spread the word that Jagmohan had asked Pandits to leave the Valley so that he could use the forces against the help-less population without any collateral damage. Nothing could be more absurd. Jagmohan joined his post at Jammu. The next day, when he was flying into the Valley, the exodus had already begun in the opposite direction. How could Jagmohan organise the exodus of Pandits scattered in different parts of Kashmir within 24 hours of his joining?

The separatists were out to garner political support for Jag- Mohan’s removal from the state because his actions were obstacles to their plan of action. It is amazing that not only Farooq Abdullah, who would launch anti-India propaganda at the drop of a hat for votes, but all political parties made Jagmohan a scapegoat as if the Governor was responsible for the deterioration of the Kashmir situation. In the past, he was asked by Rajiv Gandhi’s government to leave the state and now V P Singh’s government, which had the support of the BJP and the Left, wanted to replace him. Parties in power and in the opposition washed their hands off the issue of Pan- dits’ misery, fixing responsibility on the Governor. This is not sur- prising because the Pandits, for them, were expendables.

Advertisement