Kash Patel sworn in as FBI Director, takes oath on Bhagavad Gita

Indian-American Kash Patel was officially sworn in as the ninth Director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) on Friday, taking the oath on the Bhagavad Gita.

Emily Dickinson, the American lyrical poetess, passed away in 1886, about one and a half centuries ago. Her poems, however, continue to linger on, casting a profound influence on readers.

NANDITA CHATTERJEE | New Delhi | April 19, 2024 7:15 am

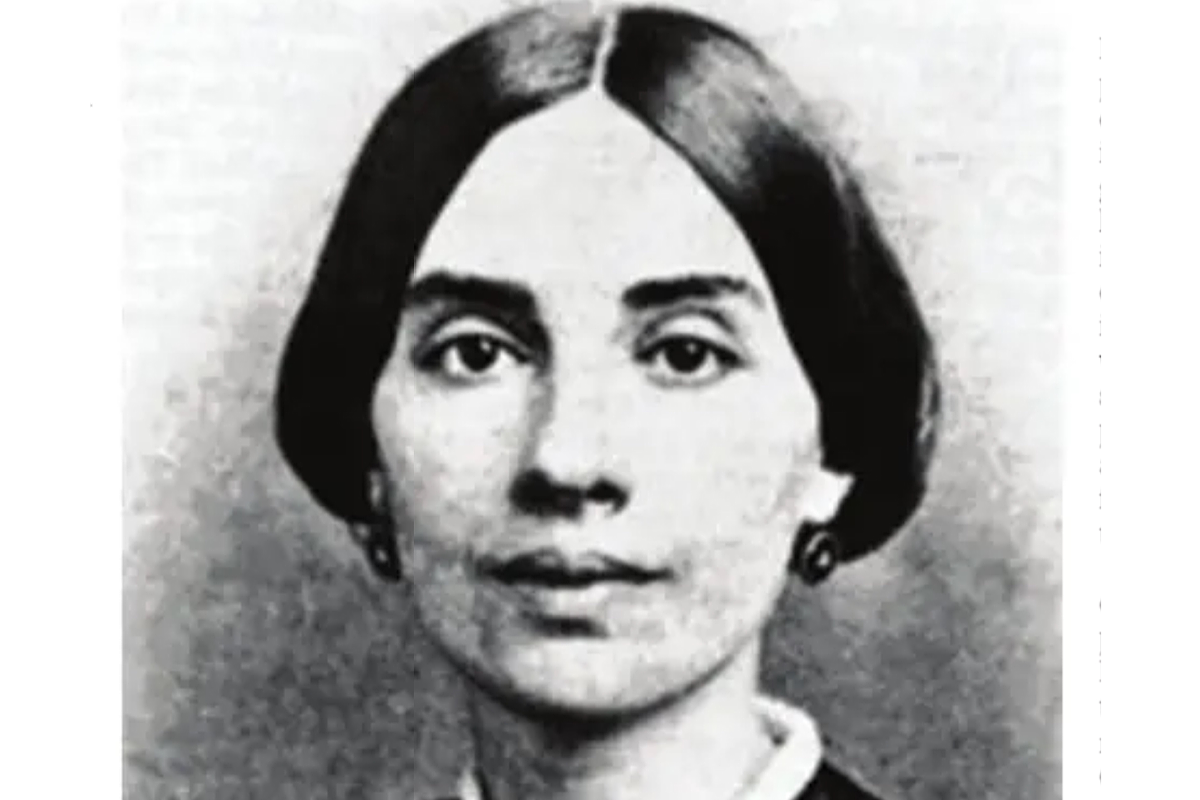

Emily Dickinson

Emily Dickinson, the American lyrical poetess, passed away in 1886, about one and a half centuries ago. Her poems, however, continue to linger on, casting a profound influence on readers. Bold original verses, short, satirical expressions, a total disregard for the conventional poetic definitions of the 19th century, a deep reflection of her personal convictions and enigmatic brilliance continue to mesmerize her readers even today.

Dickinson perceived her poetry in dualism, liberating, and at the same time leaving the reader ungrounded, wanting to delve more into the enigmatic compression. The first thought that comes to mind when thinking of Dickinson is her originality. The poetess chose to experiment with expressions to free them from the conventional restraints, crafting a unique persona in her protagonists who would imagine their escapes from societal limitations, living in an open house full of possibilities aspiring to realize the abstract someday.

Advertisement

I dwell in Possibility _ A fairer house than Prose, More numerous of Window _ Superior __ for Doors _ ***** Of visitors _ the fairest _ For Occupation _ this _ The spreading wide of narrow hands To gather Paradise__

Advertisement

Dickinson connotes an open and positive visual in “possibilities”, proud of a house of Justice with more windows that provides the perspective of more light rather than entrance through doors, hinting at her reclusive nature. Her emphasis is on poetry as opposed to prose, freeing it from the limitations of language, the dashes, the ambiguity and the capitalization. The poetess is selective in her invite, and only those using their imagination in “dwelling on the possibilities” are allowed admission, a proto-modern aesthetic distinct from the aesthetics of Walt Whitman.

The poetess appears to have communicated between herself and her poems that she preserved in her drawer, only to be made public in 1890, some years after her demise; spreading open her hands to gather paradise, invoking holiness and divinity in her abode. A recluse, mostly confined to her home in Amherst, Dickinson wrote in 1875, “Escape is such a thankful Word.” Later, she had penned

“There is another Loneliness”. There is another Loneliness That many die without__ Not want of friend occasions, it Or circumstances of Lot. But nature, sometimes, sometimes thought And whoso it befall Is richer than could be revealed By mortal Numeral

Challenging the then prevalent Victorian norms that glorified external fulfillment through societal connects, Dickinson reflects that it is solitude, in connecting with nature and thoughtful introspection that enriches and transforms the individual spirit. In the absence of punctuation, “or” appears to be conjunctive, only to disturb the meter with the addition of “s” in circumstances, a rebellion against the accustomed grammar of the 19th century.

She also introduces a capitalization of “Lot”, perhaps a reference to the Biblical story of Genesis that ends in isolation. And, very much akin to her poem “I dwell on Possibility”, Dickinson invokes divinity in nature, to be occasioned “sometimes” in the absence of societal and external stimuli. The poetess hints that beauty of nature is so sublime that the insights are too profound to “divulge / By mortal numeral” connecting her readers to experiences of similar depth, with the thought that poetry too speaks to the self as a companion of the soul. Such “loneliness”, possessed by few, is indeed a privilege in which the self reaches fulfillment and contentment through nature, divinity, introspection and poetry. In another startling composition,

“My Life has stood a Loaded gun”, the poetess writes My Life has stood __a Loaded Gun__ In Corners __ till a Day The Owner passed __ identified__ And carried me away And now we roam in Sovereign Woods __ And now we hunt the Doe __ And everytime I speak for Him The Mountains straight reply__ ***** Though I than He__may longer live He longer must__than I __ For I have but the power to kill, Without__ the power to die___

In this poem, the life of the poetess is the loaded gun, with the power in the relationship between Dickinson and her master. With the civil war as the backdrop, the poetess interprets that the potential of the loaded gun is stronger than one that has been shot. Intentionally ambiguous, the poetess appears to have the ability to change the world and kill with her poem without the need of any other to help her fire the gun.

Dickinson is the key to the potential of annihilation. Language poets of later era felt as though Dickinson spoke to them, exploring the implications of breaking the law, just short of breaking off her communication with the readers. She sweeps through the customary, chronological linearity of poetry, with syntax unusual in her era, inserting dashes and strange line breaks and capitalization. Ray Amantrout, one of the founding members of the West coast group of language poets, calls Dickinson’s style as a “witchy word choice”. At the same time, it is possible that Dickinson could have opened up the rigidity of conventional language hoping to communicate better with the reader.

American poet and scholar and an innovative poetess Susan Howe suggests that Dickinson could have been focused on a life of consciousness and recreating consciousness in her House of Possibilities, wanting to open up the space for language poets to inhabit, lifting the load of European literary custom. In this, both Emily Dickinson and Gertrude Stein had initiated a counter movement which would bring to light the infinite limits of written communication. In their unconventional language syntax, both pushed against the patriarchal literary canons policing conventional connotations.

Dickinson was fortunate. During her lifetime, she had no public audience and hence she could do what she did, scattering the laws of conventional grammar to the winds and breaking the laws of narrative and set it in the form of rearrangement of the sentences. The poetess is indeed radical, particularly when, while describing life, she takes a grammatically complete sentence, sets it next to another sentence and defies the format of conventional syllogistic propriety. Chafing against the norms of higher education being imparted to women of her times, Dickinson allied her challenges to unconventional external reading, getting into Geometry, Geology, Philosophy, Politics and even Alchemy, boldly creating a new grammar in, in contrast to, as Al Filreis of the University of Pennsylvania puts it, “humility and hesitation.”

Susan Howe, however, interprets Dickinson’s self-confessed stammering hesitation as a political act, a rejection of the culture of aggression. This is so very Dickinson as it becomes a powerful form of social and political resistance, surprising us with her conceits in penning a restless language that fails to adhere to the limits of grammatical prudery. An intensely private person, Dickinson was immensely creative, penning about 1800 poems in her lifetime. An instinctive experimenter, she played with slant rhyme, short lines, unconventional capitalization and punctuation. She also refused to give titles to her poems. Feeling entrapped by society, Dickinson sought to transcend societal mandates through her poetry, her love of nature and divinity; poetry was Dickinson’s gateway to freedom. Dickinson passed away in 1886, with her wealth of poems remaining unknown till they were first made public in 1890.

After her death, her family members found her hand sewn books or “fascicles”. Perhaps the assemblage was intended to remain private, or, as Dickinson speaks through a poem of 1863, “This is my letter to the world” hoping for a posthumous publication. Todd and Higginson had first published her works in 1890, and in 1955, a complete volume was brought out, edited by Thomas H Johnson. These, however, were in an edited and conventional form and only in 1998, with the publication of R W Franklin that the original order, punctuation and spelling preferences of the poetess were restored.

Emily Dickinson had left behind a great legacy of a poetess well ahead of her times, who could challenge societal norms and literary mandates from her home in Amherst in the 19th century. Today’s language poets owe much to her as she had freed their space, guiding them towards experimental creativity. Her pioneering contributions do deserve recognition of the creative spirit that Dickinson personifies.

(The writer is International Advisor to the UN Secretary General and former Secretary to the Government of India)

Advertisement

Indian-American Kash Patel was officially sworn in as the ninth Director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) on Friday, taking the oath on the Bhagavad Gita.

US exceptionalism is reflected in a number of ways with important political ramifications. The electoral college and the composition of the Senate violates the modern democratic principle of majority rule.

‘Great Games’ was used to describe the fierce fight by rival powers for spheres of influence in the unforgiving swathes of South-Central Asia (modern day Afghanistan), at the crossroads of civilisations.

Advertisement