When local elections in West Bengal were postponed in the first week of April in view of the coronavirus pandemic, it did not attract much attention though such engagements had also been deferred in different parts of the world, notably the mayoral polls further afield in London, Manchester and Liverpool.

But the tryst with democracy, albeit on a limited scale, slipped from public view in view of the alarming coronavirus and the balloonong afflictions and death toll. When elections can be put off with so little discussion of alternatives, such as the feasibility of a switch to postal or electronic voting, there is a risk that they are made to seem unimportant.

Advertisement

Quite true. Any election is now less important in the overall construct. While the lockdown is being progressively extended, with chock-a-block traffic and shops pulling up their shutters, the West Bengal government, for instance, has been rather muted in its response to voting.

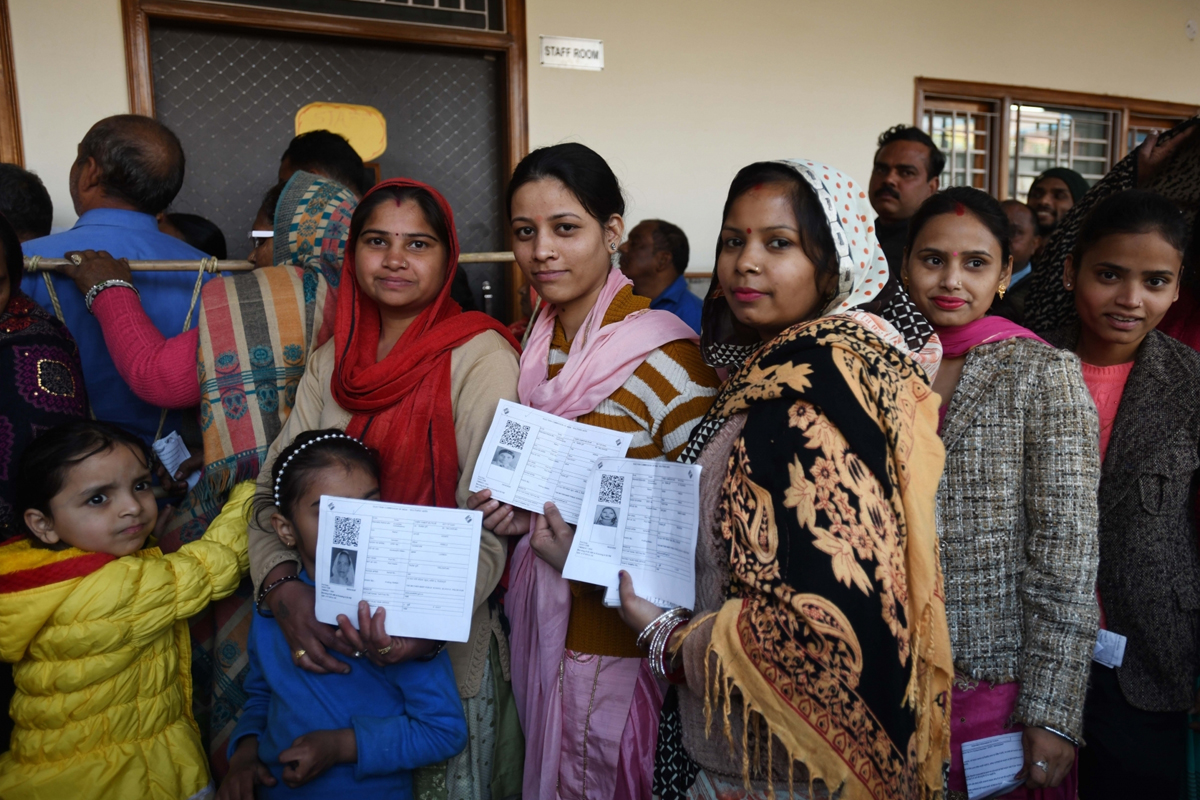

True, social distancing will be a challenge on voting day, whenever it is is scheduled. But postal or electronic voting could well be an alternative, if permissible under law. As it is, the ad hoc arrangements in several quangos, pre-eminently Kolkata Municipal Corporation and the civic body in Siliguri, have caused a flutter in the political roost.

Signals from abroad are mildly encouraging. The lockdown restrictions are easing three months after the clamp. Ergo, the issue calls out for another look. The South Koreans went to the polls with distancing and hygiene measures in April.

Other countries where elections were delayed, such as France, are now going ahead, with the mayor of Paris, Anne Hidalgo, expected to win a second term. But while the UK government has pushed on with reopening schools and businesses in defiance of warnings about continued health risks, elections appear not to inspire the same urgency.

Nor for that matter is it quite so urgent in West Bengal despite the relaxation generally. Visually, life is normal. Technically, however, the state bears witness to Lockdown Phase 5. It will take time to assess how well local councils have coped during the pandemic.

With their role in adult social care largely whittled down to that of commissioners, they are not responsible for care homes in the same way that the state’s health department is responsible for hospitals. Schools have been closed till 31 July.

But three months after the lockdown was declared, we need to reflect on how well children have been looked after, not merely in terms of online learning but in matters medical as well. Not the least because public health is integral to the functioning of municipalities.

In West Bengal’s perspective, it remains to be seen whose interests this election timing will serve. But they can’t be deferred till the cows come home.