Drivers prefer economical, easy to fill CNG autos

Shorter refuelling time, coupled with economic and environmental benefits, the compressed natural gas (CNG) is emerging as the choicest fuel among auto-rickshaw drivers in the city.

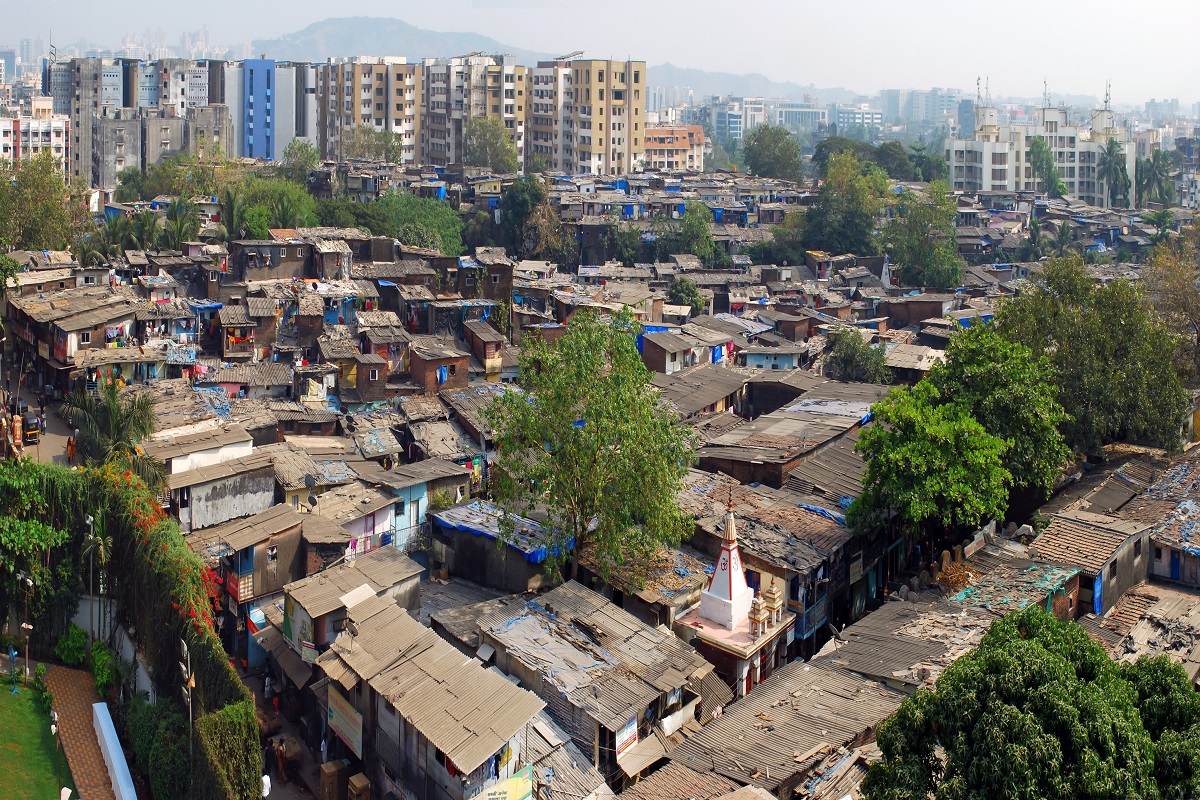

Economic inequality has persisted for long and the present global economic scenario clearly indicates it will last at least for the foreseeable future.

(Photo: iStock)

Economic inequality has persisted for long and the present global economic scenario clearly indicates it will last at least for the foreseeable future. The World Inequality Report 2022 suggests contemporary global economic inequalities in income and wealth are close to early 20th century levels, at the peak of Western imperialism. The Report tells us that inequalities within various countries have increased over the last few decades. India is no exception. The average income of the adult population in India is Rs 2.04 lakh per annum. While the bottom 50 per cent earns Rs 0.54 lakh the top 10 per cent earns Rs 11.66 lakh i.e. 22 times more.

The top 10 per cent and top 1 per cent hold 57 per cent and 22 per cent of total national income respectively while the bottom 50 per cent holds only 13 per cent. ‘India stands out as a poor and very unequal country, with affluent elites’ the Report says. The Inequality Report also highlights that income inequalities in India were high in the British colonial period when the top 10 per cent held about 50 per cent of total national income. After independence, with the adoption of a socialist approach in the economy, the share of the top 10 per cent came down to about 35-40 per cent. But economic liberalisation in the 1990s again boosted inequalities. Economic liberalisation benefitted mostly the affluent class. The theory of the so-called ‘trickle down’ effect did not work. Inequality has become the order of the day.

Advertisement

Wealth inequality tells us the same story. Average household wealth in India is Rs 9.83 lakh. The bottom 50 per cent owns almost nothing at Rs 0.67 lakh. The top 10 per cent and 1 per cent own respectively 65 per cent and 33 per cent of total wealth of the nation. Wealth inequalities are more pronounced than income inequalities. Wealth creates power and ability to control others. Some experts suggest inequality is inevitable in the run of economic progress of the nation. Economic inequality is the inevitable fallout of the neo-liberal economic system, which was adopted in India in early 1990s. This economic model is based on free market philosophy. The market will determine price, end inflation, and will allocate resources. It is also prescribed to liberalise trade and finance. Government should keep itself aloof and watch the magic power of the market. Private players in the market dominate and control the economy as well as the social life of people.

Advertisement

They channelise national resources to their own good to maximise profit ignoring society’s needs. Government extends infrastructure and other support to these powerful corporations. Market is obviously controlled by and tilted towards the powerful. It does not have its own power or self-control. So the free market is not actually free. The key messages of the World Inequality Report 2022 include: ‘Nations have become richer, but governments have become poor, when we take a look at the gap between the net wealth of governments and net wealth of the private and public sectors.’ The Report shows gradual rise in private wealth and decline in public wealth over the years.

Free-market economy has been characterised as a low wage economy with very high profits and large-scale poverty. This economic system suits the needs of a few. The economic consequences of a free or unregulated market are widespread economic and social inequality and suppression of the weak and the vulnerable. Noam Chomsky once pointed out ‘Neoliberal doctrines, whatever one thinks of them, undermine education and health, increase inequality, and reduce labour’s share in income, that much is not seriously in doubt’ [‘Profit over People’]. So, we observe today that corporations are building shopping malls and not libraries. The economy stands on the hard toil of the labourers.

But very low income of labourers in India is a major concern and predictably the most basic cause of inequality. Majority of people subsist on a meagre annual income of Rs 54,000. This amount is insufficient for a family of four to survive decently. Even permanent workers in organised sectors are not in good shape. They earn a little over minimum wages. Archana Aggarwal in her book ‘Labouring Lives’ has narrated the plight of the workers in the garment and automobile industries. She observed “Many industrial workers still depend on agriculture to meet part of the family’s expenditure.” She also observed “…the high costs of living and declining wages have led to the phenomenon of ‘reverse remittances’ where the village economy subsidises the workers’ living expenses.”

It has become the trend in large industries today to employ more and more contractual labourers in place of regular and permanent workers at a lower wage and in most cases without any written contract and without paid holidays. Even contractual workers are being replaced by trainees or apprentices. Their jobs can end abruptly. Aggarwal has shown that regular skilled workers earning Rs 29,000 per month had been replaced by contractual workers at monthly wage of Rs 6,600. This phenomenon is increasingly being observed in the organised sector. The data shows that the proportion of contract workers in factories has risen from 23 per cent in 2002-03 to 36 per cent in 2017-18 and further to 40 per cent in 2021-22. The work does not differ much but wages differ significantly.

Companies gain at the cost of the labourers which add to their profits. They spend more in CSR activities depriving their own employees. In another example, Aggarwal has shown that the chief executives of some companies are earning 750 times to 1000 times more than the average worker. This is stark inequality and an unpalatable fact. Self-discipline should be imposed by the corporations by fixing rational pay-outs to CEOs. Otherwise, we will continue to watch mindless exhibitions of wealth of individuals in our poor country. About 90 per cent of the workforce in India works in the unorganised sector. Here, their daily wages are protected by the Minimum Wages Act 1948. But Aggarwal has rightly commented that “On the ground, this has become maximum paid to most workers. It has become the ceiling rather than the floor.”

The minimum wage is the minimum subsistence for the worker. It is not sufficient for the survival of his or her family. Industry today indulges itself by paying lower wages to its workers who are mostly contractual. So, it has become imperative to protect the interest of the workers. The law must ensure it. Principle of same wages for the same jobs should be implemented. On the other hand, the statutory Minimum Wages should also be increased substantially for a decent living of labourers with their families. These measures will certainly increase the average earnings of a huge work force which may result in decrease in income inequality to some extent.

State intervention is necessary in market activities as well as in redistribution of economic wealth among the population. Government should take policy measures so that the economic and social power is not concentrated in a few hands but reaches the masses. Economic empowerment of the masses alone will reduce inequality. (The writer, a cost accountant, was General Manager of a state power utility.)

Advertisement