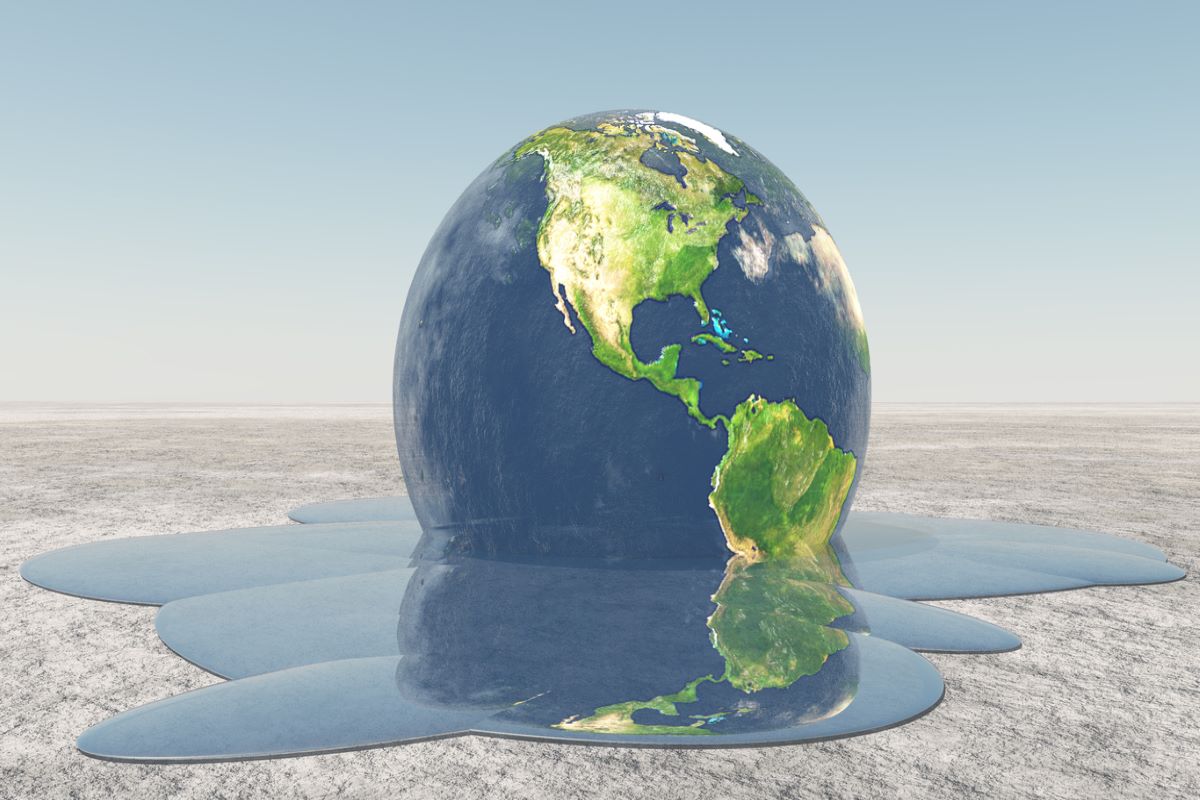

Will the world lose all its glaciers?

By the end of this century, up to two-third of all glaciers worldwide could disappear – an alarming scenario that threatens the future of water supply in many places.

A recent UN climate panel report and the Russian attacks on Ukraine’s nuclear plants do not offer much hope. Unless we think of more radical solutions, eco-shaming may not be enough to prevent us from facing a catastrophic future.

representational image (iStock photo)

Over the past 25 years, the richest 10% of the global population has been responsible for more than half of all carbon emissions. Rank injustice and inequality on this scale is a cancer. If we dont act now, this century may be our last. – António Guterres, UN Secretary General.

Even as the world grapples with the almost intractable issue of climate change, without a long-term solution in sight, a new term has found its way into the environment protection lexicon. Eco-shaming had its roots in Sweden when the term flygskam (flight shame) was coined in 2018. With an eye to minimising environmental pollution, there was an active discouragement to take flights, especially for shorter, domestic journeys. Since then, it has gathered momentum, making its presence felt on markets and brands. This is as much a result of the ‘green’ pressure’ as it is of manipulating consumer behaviour.

Advertisement

Product and service companies are realising that the carbon footprint of their offerings is making a discernible difference in consumer choice. What was earlier seen to be an awareness issue has slowly become a social imperative. Marketers have cashed in on this opportunity to position their products by using guilt as an effective psychological ploy.

Advertisement

From electric cars to shoes made from plastic waste, they are offering products which clearly reflect their ‘environment-friendliness’ while also nudging consumers to believe that not buying these products would make them environment unfriendly. With growing acknowledgement and acceptance, what was earlier perceived to be exclusive, has become commoditised.

Elon Musk’s electric cars are getting into the mass market, while shoes made from ocean plastic are being sold at affordable prices. As a result, recycling their plastic, having less meat and flying less are activities being practiced to show growing eco-awareness. This persuasive inclination of marketers finds reflection in Foundation Earth, an organisation set up in the UK at the end of 2021.The purpose was to bring about awareness about the eco-friendliness of our food choices.

Foundation Earth has introduced front-labelled environmental scores on various food products. So, buyers get to know the environmental score along with the nutritional score of the specific food item. The score is gathered from the parameters of carbon, water usage, water pollution and biodiversity. Companies like Starbucks, Costa Coffee, Tesco and Marks and Spencer are participating in this initiative.

While it has a cheekily exploitative ring to it, eco-shaming has provided the much needed fillip to environmental awareness. While the necessity of building eco awareness at the individual level is incontestable, we all realise that it is not enough to achieve and maintain the target of keeping the global warming up to 1.5 degrees Celsius. This can only happen when something akin to eco-shaming impacts large corporations and the countries which encourage it.

The fact that fossil fuel companies are the real culprits is among the worst kept secrets in the world today. Compounding the problem is the fact that this act is being perpetrated by a handful of corporations who are largely concentrated in developed countries. These organisations flagrantly disregard the warnings of ecologists and environmental scientists, as they continue to erode the planet’s resources, making empty promises to bring in the requisite measures to stop the climate imbalance.

Interestingly, the antecedents of this erosion of natural resources go as far back as the 15th and 16th centuries, where, in the name of civilisation and progress, there was systematic plunder of natural resources by colonial conquistadors, who emerged largely from what we now refer to as Western countries.

As tellingly described in Amitav Ghosh’s most recent book, The Nutmeg’s Curse, this destructive desire germinated from the idea of conquest where the Earth was seen as a “vast machine, made of inert particles in ceaseless motion” in which the subjugation of the non-human, trees, animals and landscapes was part of the journey towards modernity. As a consequence of this flimsy logic, huge biological and ecological imbalances have threatened our planet’s existence.

Nowhere are the contradictions of our current civilisation demonstrated so starkly as in the climate crisis, where progress and devastation are inextricably linked. While publicly proclaiming the need to take active steps to save the planet, governments and corporations continue to exhibit their collective indifference in trying to contain the severe environmental imbalance.

As climate activists like Greta Thunberg continue to mobilise opinion against corporate emitters of carbon, and organisations like TreeandHumanKnot are standing up against deforestation, we realise that strident protests alone will not provide longterm solutions. Which is why affirmative action, by way of divestment of stocks in energy corporations and other environmental culprits, needs to be welcomed.

Starting in 2011, when noted environmentalist Bill McKibben said that “we need to revoke the social license of the fossil fuel industry” the movement to stigmatise fossil fuel companies through divestment has slowly gathered momentum. As of 2021, this has resulted in $14.5 trillion divestment from fossil fuel companies.

The conversation is certainly changing. Whether such radical initiatives will have long term results, however, remains to be seen. A recent UN climate panel report and the Russian attacks on Ukraine’s nuclear plants do not offer much hope. Unless we think of more radical solutions, eco-shaming may not be enough to prevent us from facing a catastrophic future.

(The writer, a former CEO of HCL Care, runs a consulting firm.)

Advertisement