Air India’s HR policies, draconian, unethical: Pilot bodies

"The pilots are being subjected to a hostile work environment," says a joint letter by the Indian Commercial Pilots' Association (ICPA) and Indian Pilots' Guild (IPG).

At Kanpur, the large number of tanneries merrily continued discharging untreated toxic

waste into the Ganga, but nobody was there to prevent it, least of all to prosecute them.

Common Effluent Treatment Plants had been constructed, but none of them was in

working condition, partly due to technological problems and partly due to lack of electricity

and lack of coordination to share the costs

Parimal Brahma | January 8, 2023 10:43 am

SNS

The Environment (Protection) Act, 1986 has completely failed to control air pollution in Delhi NCR and the country as a whole. On the other front of water pollution, it has so far been ineffective to clean up the rivers and the water bodies. It also could not regulate solid waste management as the mountains of garbage continue to pollute the cities.

The flagship programme of the Ministry of Environment, Forests and Climate Change had been the Ganga Action Plan. At the initiative of Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi, the Ministry of Environment created in 1985 a large division for the ‘Ganga Action Plan’, headed by an Additional Secretary and endowed with a huge budget. It was a multi-pronged project with a string of programmes and schemes aiming at bringing back the pristine glory of the Ganga.

Advertisement

The programme had been in operation since 1986 and till 2014, hundreds of crores of rupees had been spent on various schemes spread over the entire Ganga basin starting from Gangotri to Sagar Island at the estuary of the river. Funds were sanctioned by the Central Government, but the specific schemes had to be implemented by the state Governments of Uttar Pradesh, Bihar and West Bengal.

Advertisement

By 2015, the Ganga Action Plan had already completed 30 years with no visible impact which prompted people to question the wisdom and effectiveness of the project. The Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB) was entrusted with the task of monitoring the water quality of the Ganga and the Board had accordingly set up monitoring stations at certain strategic places.

They sent periodical reports which indicated that the water quality of the Ganga had generally been improving but the progress was very slow. Occasionally, the Ministry would be thrilled to get reports that dolphins and turtles had been sighted near Varanasi and Allahabad leading to the conclusion that the water quality and the biological oxygen demand (BOD) must have improved.

But the ground reality told a different story. The CPCB had been sending reports which would please their bosses in Delhi and what the Ministry would like to hear. Members of the public, environmental activists and voluntary organisations pointed out that far from being restored, the condition of the Ganga was fast deteriorating. There is a strong belief that Ganga-Jal which is used for all pujas and auspicious occasions can never collect bacteria or sediment even when kept in vessels for years and the river purifies itself.

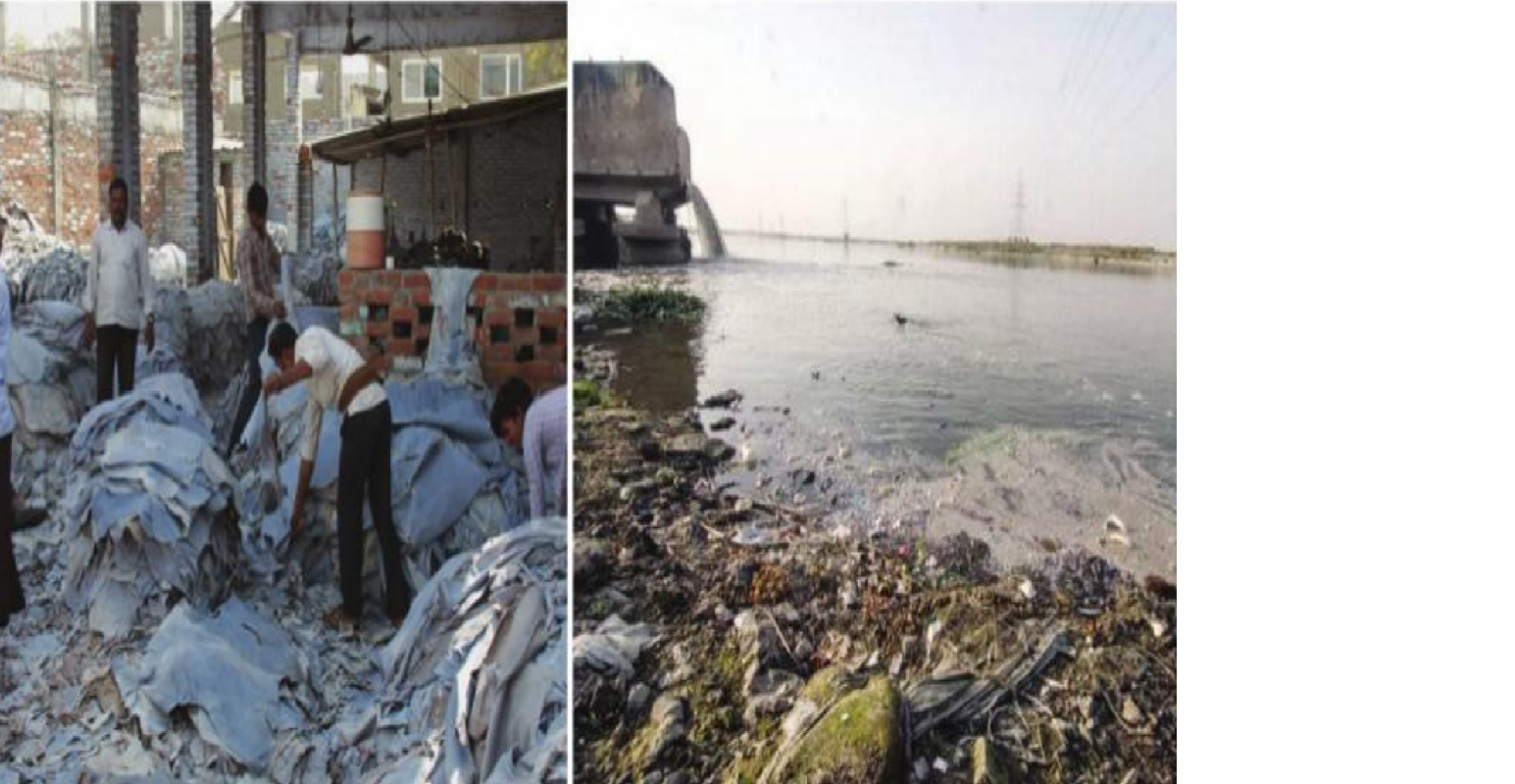

This age-old faith gets a rude shock when people visit the Ganga at Kanpur, Allahabad, Triveni Sangam, Varanasi, and further downstream at Patna where Ganga water is not fit even for bathing, what to speak of drinking. At Kanpur, the large number of tanneries, totally against all existing orders, merrily continued discharging untreated toxic waste into the Ganga, but nobody was there to prevent it, least of all to prosecute them.

Common Effluent Treatment Plants (CETP) had been constructed, but none of the CETPs was in working condition, partly due to technological problems and partly due to lack of electricity and lack of coordination to share the costs. Since these plants required substantial investment and their maintenance was also an expensive proposition, it was perceived that sharing of costs among the tanneries would make sense. Unfortunately, common responsibility was nobody’s responsibility and the system became non-functional because of disputes, nonpayment by smaller units and lack of a common administration.

The end result was that hundreds of tanneries at Kanpur were daily discharging several tons of foul and toxic waste-water to the river making the Ganga at Kanpur absolutely polluted. The effluents even made the holy river unsuitable to support aquatic life including fish. Electric crematoria built in the major towns all along the Ganga basin continued to remain non-operational except in West Bengal. Dead bodies continued to float on the sacred river. And quiet flowed the holy Ganga but there was not a drop to drink.

The condition of river Yamuna had been worse. Plans after plans had been drawn up by the Ministry of Environment with the active assistance of the World Bank to clean up the Yamuna mainly through construction of Common Effluent Treatment Plants (CETP) which would prevent untreated industrial sludge and municipal sewage flowing into the river and also through construction of oxidation ponds at various places. But nothing improved the ground situation during the last three decades; on the other hand, the condition of the river went from bad to worse.

The overflowing population of Delhi which increased from 4 million to 24 million in six decades (1950-2010), spilled on to the river fronts, the migrant population occupying large parts of the riverbed for habitation. Finding that Yamuna had been emasculated to such an extent that it was incapable of causing floods, the immigrant workers merrily established settlement colonies along the river banks. The CETPs have never really worked. The oxidation ponds slowly died out and gave way to housing colonies.

The untreated industrial waste-water and the sewers of entire Delhi and of the surrounding towns continued to flow into the river. On the other hand, to meet the everincreasing demands for water from an evergrowing population, more and more water was being drawn out of Yamuna.

The barrage constructed north of Delhi diverted almost the entire water of Yamuna to meet the drinking water needs of Delhi and contributed to choking of the river to death because there was hardly any water left for free flow downstream. What continued to flow was nothing but a mixture of sewer water, industrial effluents and sludge, waste materials of the cremation grounds, garbage, and plastic bags.

Occasional mass campaigns by NGOs to clean up the river have had only ritual values without substance. There is perhaps no major river in the world which is as polluted as the Yamuna. It is virtually a flowing drain occasionally getting life-support from the upstream dams and barrages which are forced to release surplus water in the monsoon season causing overflow of its banks and unnatural floods. But for all practical purposes, the mythical and romantic river Yamuna is dead. It is doubtful if the Central Government and the Delhi Government will ever be able to revive and restore the Yamuna to its pristine glory as has been done for the Thames in London and the Seine in Paris.

The Indian consciousness adoring the divine love stories, the songs of Gita Govindam and the millions of arts, dance and music forms associated with Radha-Krishna and the Yamuna will receive a rude shock to imagine about this river today. The Ganga Action Plan in various avatars during the first 30 years of its existence – GAP-I (1985), GAP-II (1993), National River Conservation Plan (NRCP1995), and the National Ganga River Basin Authority (NRGBA2009) – failed the nation.

Some of the failures were highlighted by the CAG’s Report No. 5A of 2000 on the Ganga Action Plan. In 2014 when a new regime came to power at the Centre, the entire Ganga Action Plan was taken out of the Ministry of Environment and placed under a newly created Ministry of Jal Shaki. The National Mission for Clean Ganga (NMCG) or Namami Gange was launched in 2015 as an umbrella programme, integrating the earlier plans and schemes with new initiatives and the clean-up campaigns.

The National Council for Rejuvenation, Protection and Management of River Ganga (National Ganga Council) with the Prime Minister as the Chairman was created under the EPA in 2016 as a supreme decision-making authority for the entire Ganga Basin Management. Namami Gange with an initial outlay of Rs. 20,000 crore has been a gigantic multi-pronged programme for the entire Ganga basin including all the tributaries (Yamuna etc.) and the catchment area. The Ganga basin constitutes 26 per cent of the country’s land mass and supports 43 per cent of India’s population.

According to the Ministry of Jal Shakti, so far 315 projects worth Rs.28,854 crore have been sanctioned and are under operation. In addition, a “Clean Ganga Fund” was created receiving contributions from individuals, institutions, corporates, NRIs and OCIs, which is supporting specific programmes with people’s participation. While significant progress has been made towards cleaning up the Ganga, everything is not fine with the grand project.

There is a question mark about the real achievements against the blitzkrieg of publicity. The Performance Audit Report (No.39 of 2017) of the Comptroller and Auditor General on ‘Rejuvenation of River Ganga (Namami Gange)’ has revealed a number of deficiencies including lack of long-term action plans for the Ganga basin, non-identification of conservation zones, tardiness in project implementation, non-utilization of allotted funds, non-establishment of Ganga Monitoring Centre etc. But, with the Prime Minister personally monitoring the progress as head of the Ganga Council, hopes are high for the possibility of purification of mother Ganga.

Advertisement

"The pilots are being subjected to a hostile work environment," says a joint letter by the Indian Commercial Pilots' Association (ICPA) and Indian Pilots' Guild (IPG).

Advertisement