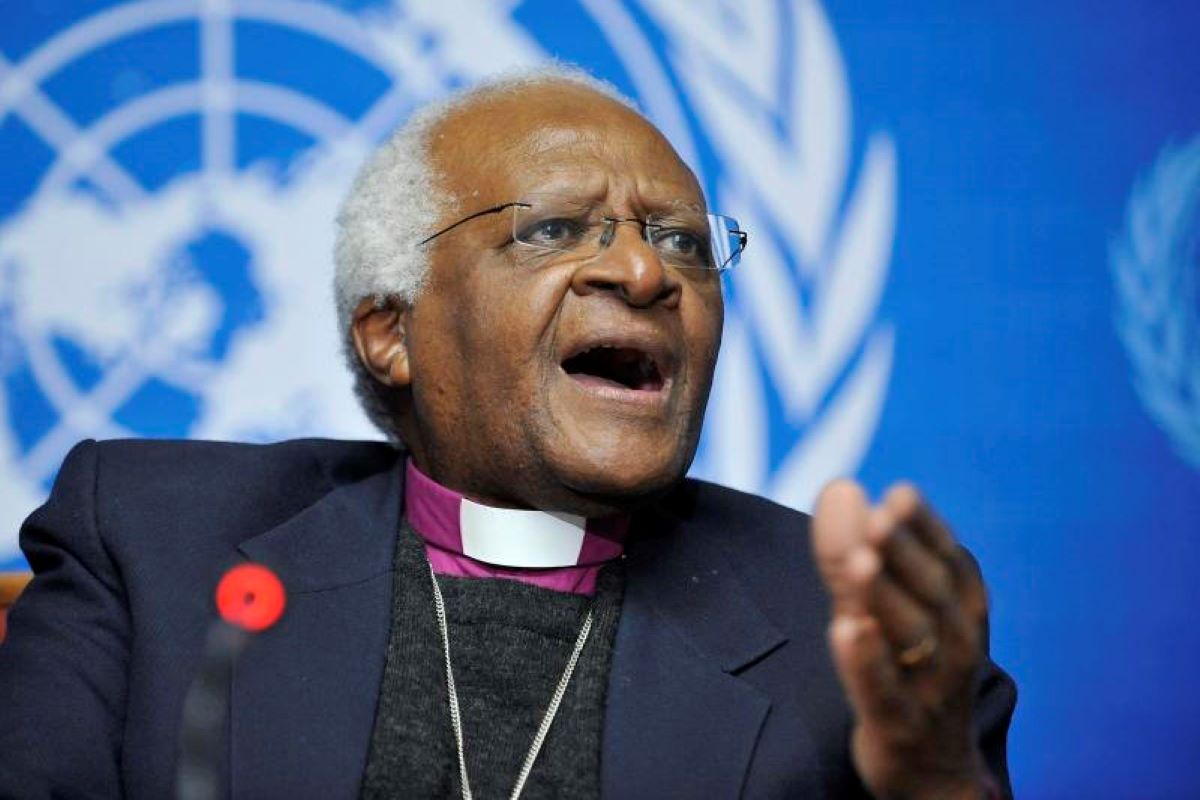

There was not another man in the world on Sunday whose passing at the ripe old age of 90 could have saddened so many hearts. Desmond Tutu’s pulpit and spiritual oratory helped end apartheid, and this indeed must rank as his primary contribution to humanity. In death, he personifies the contemporary

truism that “black lives matter” not the least because he was the leading advocate of peaceful reconciliation under black majority rule.

As leader of the South African Council of Churches and as the Anglican archbishop of Cape Town, he brought the Church to the forefront of the black South African’s decades-long struggle for freedom. He was a powerful force for non-violence in the anti-apartheid movement, a sterling quality that earned him the Nobel Peace Prize in 1984. When that movement triumphed in the early 1990s, he prodded the country towards a redefined relationship between its white and black citizens. As chairman of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, he had gathered testimony that documented what he called the viciousness of apartheid.

Advertisement

As a firm believer in the principle of restorative ~ rather than retributive ~ justice, he said , “You are overwhelmed by the extent of evil, but it was necessary to open the wound and cleanse it”. Archbishop Tutu preached that the policy of apartheid was as “dehumanising to the oppressors as it was to the oppressed”.

Within South Africa, he sought to bridge the rift between the black and the white; offshore, he called for economic sanctions against the South African government to force a change of policy. Much as he criticized the apartheid leadership, he also disapproved of the leading figures in the dominant African National Congress, which came to power under Nelson Mandela in the first fully democratic election in 1994.

In 2004, Tutu accused President Thabo Mbeki, Mandela’s successor, of pursuing policies that enrich a “tiny elite while too many of our people live in gruelling, demeaning, dehumanizing poverty. We are sitting on a powder keg.” Although he and Mbeki later reconciled, Archbishop Tutu was acutely aware of reality even under black rule.

He was unhappy about the state of affairs in his country under its next President, Jacob Zuma. “I think we are at a bad place in South Africa,” he once told the New York Times.

Then in 2011, when the ANC was accused of corruption and mismanagement, Archbishop Tutu remarked, “This government, our government, is worse than the apartheid government. Zuma, you and your government don’t represent me. One day we will start praying for the defeat of the ANC government. You are disgraceful.” His words turned out to be prophetic when in 2016, an alliance of religious leaders in South Africa joined other critics in urging Zuma to quit. As critical of corruption under the blacks as he was to white supremacy, Archbishop Desmond Tutu could famously call a spade a spade. With his passing, the world is poorer.