Jaishankar refutes claim about global democracy in trouble

Rejecting the concerns about democratic decline, he highlighted the growing voter participation in India, noting that 20 per cent more people vote today than they did decades ago.

Feudalism is a centuries-old concept. In the medieval ages, the kings and nobility were the absolute owners of the land. Serfs worked on the land to concoct value, but the landlord appropriated most of that value.

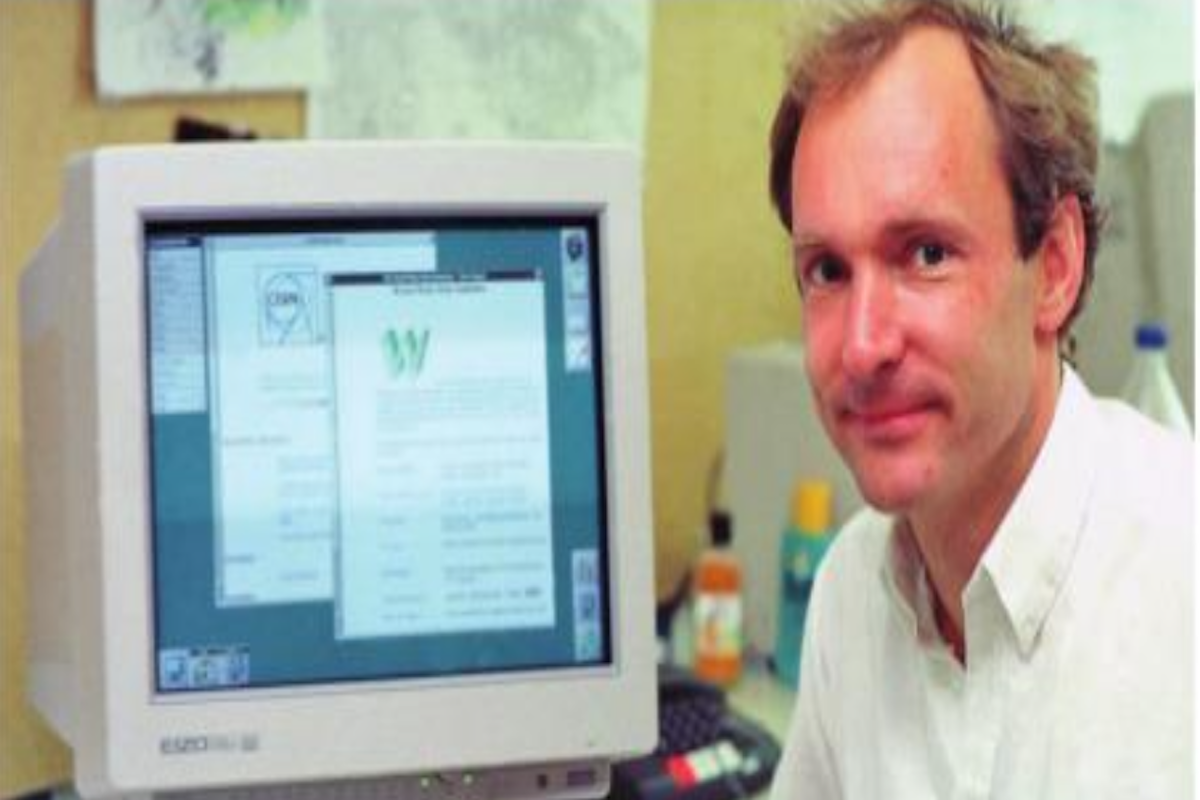

The birth of the World Wide Web (WWW) came with a promise. It was perceived as a new democratic space – a vast new common – developed initially with taxpayer funding and weaved to ensure that no single entity owned or controlled the entire network. It was seen as a space for using and exploring, with no established and well-defined rules, boundaries, or existing economic structures. How- ever, the internet did not remain free for long as it soon started evolving toward the very antithesis of its original decentralized roots. Regrettably, our current digital ecosystem, called the ‘platform economy’, bears substantial similarity to the medieval economic order, known as feudalism. Day by day, it’s getting more entrenched.

Feudalism is a centuries-old concept. In the medieval ages, the kings and nobility were the absolute owners of the land. Serfs worked on the land to concoct value, but the landlord appropriated most of that value.

Advertisement

In our modern digital ecosystem, instead of farm produce, today, the new asset class is data (with personal data becoming the world’s most precious commodity) – which is created by us (the users) but seized by digital landlords (dominant tech companies). The feudal lords exploited the medieval common, and the once free internet common is now colonised by these tech giants (Google, Amazon, Apple, Microsoft and Facebook). Like the medieval feudal lords, they want- ed to control our personal space and wanted us to be hard-working peasants.

Advertisement

Just as the feudal economy was based on cheap labour, the digital economy exploits and extracts user data, connectivity, and sociality. Users participate on platforms, barely knowing the data they capitulate, and that data is then used to create value solely for the platform owners. We are now at a juncture where we must agree to the company’s terms; otherwise, we can’t use that technology. The more automated our lives will become, the easier it will be for those who wish us harm to interfere and tamper with our lives. Pegasus Spyware is the most recent known example of the same.

Medieval feudalism was based on the exercise of authority, whereas digital feudalism is participatory. These digital feudal lords have entered the picture with the promise of exceptional user experience, efficiency, and convenience. The prices users pay are dependency, surveillance, loss of freedom and democracy. Even algorithms are being developed in ways that enable tech firms to thrive from our past, present and future behaviour – what Professor Shoshana Zuboff at Harvard University describes as our ‘behavioural sur- plus’.

In most cases, digital platforms already know our choices better than we do and can push us to behave in ways that produce still more value. Do we want to survive in a society where our deepest desires for individual agency are up for sale? While we all benefit immensely from digital services such as Google search, we unequivocally didn’t sign up to have our behaviours indexed, shaped and sold. These algorithms have indeed been used to improve public services and the well-being of all people. These same digital technologies are now being used to undermine public services, tamper with individual privacy, and destabilize the world’s democracies – all for vested benefits.

From a democratic aspect, the platforms pose even more crucial questions: Will technology be the equalizer or further widen the gap between the digital haves and have- nots? Should we adjust to living in this neo-feudal world? Which laws need to be re-examined, and what new directions do we require? Should tech innovators be content to potter at the edges or strive to strike at the roots? We may not find the solutions right away, but let us start by identifying all the questions that need to be asked.

Adam Smith’s conception of a ‘free market’ was free from rents, not the state. So, there is an urgent need to regulate big tech and bring it under the principles of transparency and justice. Democracies across the globe like Australia and Canada have enacted legislation like News Media Bar- gaining Code and Bill C-10, respectively, to mitigate the risks posed by Big Tech.

India must do something too. The Privacy and Data Protection (PDP) Bill should be brought forth and enacted as law. Other legislation should be carved for systematic and rigorous parliamentary oversight over the tech companies. Digital governance should be rooted in our Constitutional principles.

Digital Feudalism is getting established day by day. If left unchecked, this will restrict our future innovation and participation. As we progress, we must ensure that technology is our servant, not the other way round. We must force these digital feudal lords to serve us and keep us safe. We have to ensure that even as we lease ourselves, our data and our rights to these digital feudal lords in return for their technology, we must keep some control. Our future is at stake.

(The writer is an independent researcher associated with the History of Science Society and a former elected student fellow of Royal Anthropological Institute, UK.)

Advertisement