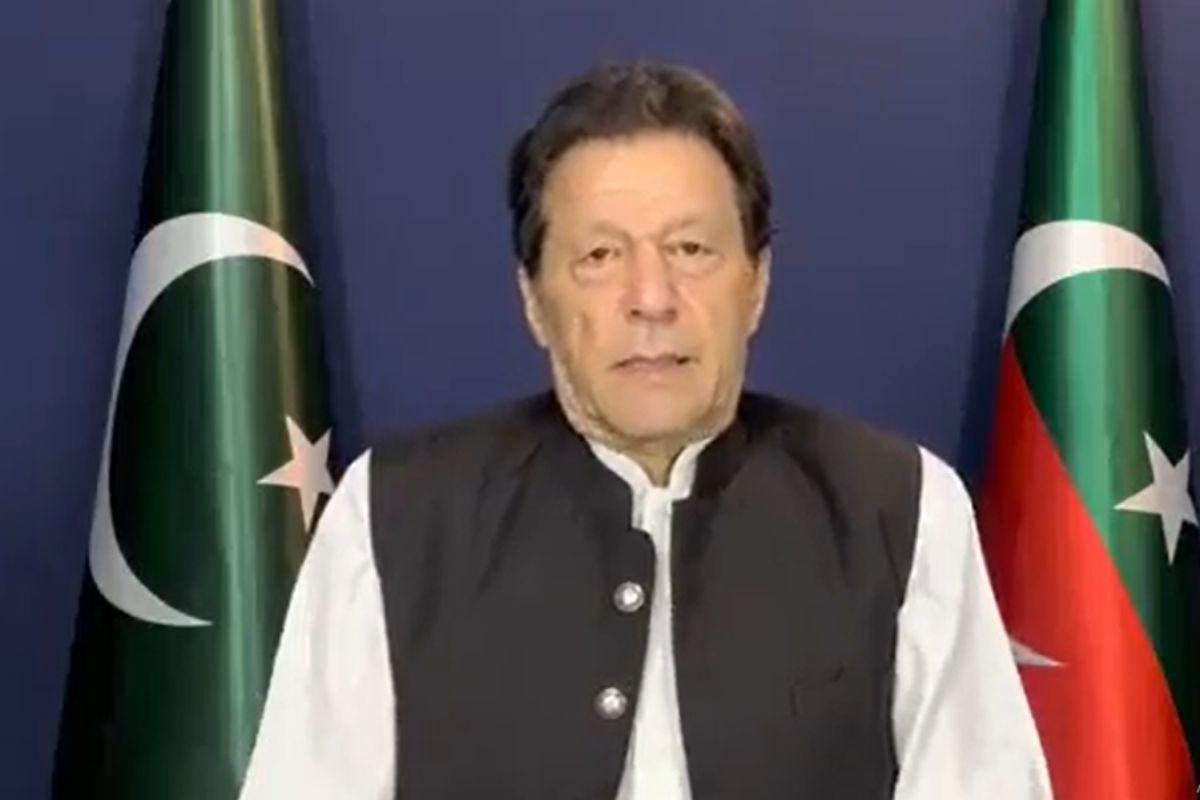

Former Pakistan Prime Minister Imran Khan’s confrontation with the military establishment has now devolved into an existential, zero-sum fight between arguably the country’s most popular politician and its most powerful institution. Mr Khan, once the military’s favourite, has over the past year stoked popular resentment against the army, which he blames for his ouster.

The attacks on military buildings after Mr Khan’s arrest (though he was subsequently enlarged on bail) damaged the institution’s veneer of invincibility, writes Brookings scholar Madiha Afzal. The military, an institution deemed ‘untouchable’ has not taken kindly to the rebellion. It has responded forcefully to the protests on 9 May, terming it a “black day” and asserting that civilian perpetrators of the violence and arson will be tried in military courts.

Advertisement

Trying civilians in army courts would violate Pakistan’s obligations under international human rights law, adds Afzal, and most experts concur. But Pakistan’s National Security Council backed the military’s decision and its civilian government has lined up behind it, dealing a blow to the Constitution and rule of law. Last week, an anti-terrorism court in Lahore allowed the handing over of 16 civilians to the military for trials.

So, what policy options does Delhi have in dealing with a failed state on its border? The short answer is to double down on its hard line on engagement with Pakistan while the latter stews in the mess of its own making. In this respect, even Washington has long since moved on from its erstwhile efforts to push for a détente between the South Asian neighbours. The USA has, perhaps, finally understood the Indian position that while it is true that one cannot change one’s neighbours, one cannot be held prisoner by them either.

This appreciation of the facts on the ground – that an army veto is embedded in Pakistan’s governance structure and that Islamabad continues to deploy cross-border jehadi terrorism as an instrument of state policy against India especially in Jammu and Kashmir, fosters radicalisation in South Asia, and is itself the victim of the ‘snakes in its backyard’ – has come in the wake of Washington’s own pivot away from the Af-Pak region.

That’s the nature of geopolitical realities and their constant realignment based on national interest. Washington can hardly complain if India sticks to its stand of zero tolerance given how it is handling ties with Islamabad after its withdrawal from Afghanistan in 2021. The USA has focussed exclusively on security, counterterrorism, and military engagement through the state department, while the White House has adopted an entirely hands-off approach. Washington has, additionally, evinced no interest in establishing bilateral ties premised on “geo-economics” – Islamabad’s catch-all phrase for trade, investment, and conne