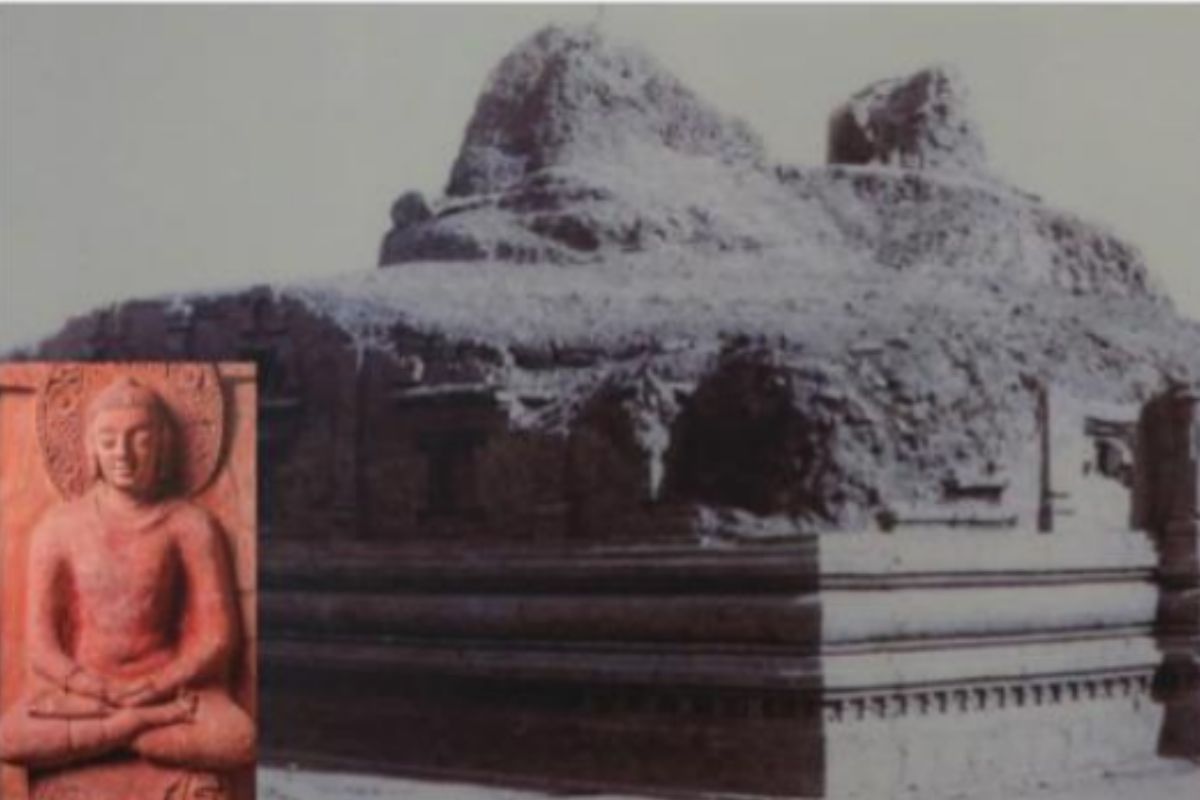

What would an institu- tion do with 297 mo- ulded bricks and ar- chitectural fragmen- ts; five large seated Buddha ima- ges in high relief; and a smaller figure within a niche of a stand- ing male figure holding a flower in relief; two roundels and rec- tangular bricks depicting the image of Kubera, a few rectan- gular bricks bearing the proba- ble image of Jambala, a large of number of sun-dried clay tablets and fragment of a stone depict- ing a Jataka tale? If the institution were enga- ged in research-writing and cur- ating like the Chhatrapati Shiva- ji Maharaj Vastu Sangrahalaya (CSMVS), Mumbai, what would emerge, evolve and develop from the collection would be a full-length study of Buddhist architecture and the discovery of a ‘lost stupa’ at Kahu-jo-daro in Sindh, Pakistan. The focus would be on the archaeological site in Mirpurkhas town, ren- owned for its terracotta art, that would lead to understanding facets of art history, cultural his- tory and religious inspiration with its seemingly infinite shor- es of understanding of how our ancestors lived, offered prayers, and celebrated their lives. In more ways than one, an ancient past would be reconstructed for the benefit of our globalized audiences. Buddhism in Sindh does so- und puzzling at first. For too long Buddhism was thought as growing, radiating, and becom- ing a major religion from the east: with its centres in today’s Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, Odisha, Andhra Pradesh; and later parts of Madhya Pradesh and Gujarat, with the movement to Tibet, Mongolia, China, and Sri Lanka giving Buddhism its global char- acter. The CSMVS research which commenced in 2008, and reach- ed culmination in 2022 with the publication of ‘The Lost Stupa of Kahu-jo-daro’, sub-titled ‘An at- tempt at reconstruction’, takes us through crossroads of culture where Gandhara up in mountai- ns and valleys of north-western Pakistan, Mathura along the Indo-Gangetic belt, Ajanta in the Deccan plateau and Rajgriha in the plains of Bihar contributed and influenced the art-forms discovered at Kahu-jo-daro in Sindh. Come to think of it, cen- turies and millennia ago, cultur- al ties between Rajgriha in Bihar and Roruha in Pakistan were a reality, and today, the story is dramatically and traumatically different! For Sabyasachi Mukherjee, director general of CSVMS who helmed the research, to say it was an immensely difficult task would be an understatement as the project began without ins- criptions or literary evidence. “Kahu-jo-daro was remote, and beyond our reach and my mate- rial resources were only those in the CSMVS collection,” he said, acknowledging the contribution of a line of venerable historians- art historians and curators like Dr Moti Chandra, Dr Kalpana Desai, Dr Devangana Desai, and Dr Pratapaditya Pal. Their col- lective knowledge and pioneer- ing works gave the ‘lost stupa’ research its new direction, high- lighting the riverine culture, ur- ban centres, trading towns, be- sides significance of religious places where people prayed, contributed their earnings, keeping places of worship alive through cen- turies. In 1909 the ‘lost and found’ stupa story began with British archa- eologist Sir Henry Cousens, who was the first to have ex- cavated the Kahu- jo-daro site. Fifty years earlier, Gen- eral John Jacob, acting commis- sioner of Sindh, had noticed the dilapidated Bud- dha site but not realised its historical significan- ce. In 1859, James Gibbs, anoth- er senior official, described the site as remains of a brick plat- form and even excavated the upper part of the mound. His diary entry recorded finding an earthenware pot filled with mud and pieces of amethyst and crystal; whereabouts of this pot or vase are unknown. Sir John Woodburn, the col- lector of Hyderabad (Sindh) in 1894, contributed to the story as he accidentally rescued a large painted terracotta seated Bud- dha image, and the head of a second image, from railway con- tractors. As in the case of Moh- enjodaro, the largest of Harap- pan metropolises in Sindh, it was railway workers-contractors who were digging and using bricks for laying local railway tracks, having no idea of how old the bricks were nor their signifi- cance. To imagine that bricks, of uniform size and shape, sur- vived two millennia and were now laying the foundation of a modern transport in early 20th century! Sir Cousens, having begun excavations in 1909-1910, noted that despite railway workers dig- ging the bricks, there was so much of the stupa remaining at the north-end of the site. He remained true to his training as Surveyor and Superintendent at the Archaeological Survey Department of India when he documented, catalogued, and surveyed the monuments in his charge across western India. Not only Kahu-jo-daro, but Ahmed- abad, Champaner and Bijapur owe much to his perseverance and diligence. His book ‘The Antiquities of Sind with Histori- cal Outline’ is regarded as a sem- inal work and provided a credi- ble platform upon which the CSMVS built its research. Owing to scarcity of archae- ological and literary material, it is difficult to know when and how Buddhism found its footing in the Sindh region. In the nor- th-west, it was the Gandhara re- gion where Budd- hism took deep roots, thanks to efforts of the Mau- ryan Emperor Asoka. Explained Sabyasachi Mukh- erjee in ‘The Lost Stupa’, “the great river Sindhu, whi- ch is the Sanskrit name of river In- dus, passed throu- gh the valley from the north to the south and acted as an important tra- de, religious and cultural connec- tion for the Indus Valley, Punjab and the Gandhara region.” This riverine connection, water-highways of the ancient world, had a continuing and deep impact on Sindh’s social, cultural, and economic history, providing crossroads and bridg- es for people of the region. Bud- dhism as a religion and way of life found adherents in Sindh. “It is very important for global citi- zens, especially the young, to understand that (the) Indian sub-continent was always part of the globalized world,” said Mukherjee, referring to the pre- sent era of globalization which most netizens feel is a historic unique one. Kahu-jo-daro in Mirpurkhas, he emphasized, is not an isolated instance of artis- tic activity in the area. He drew links between this site of the ruined Buddhist stupa with Tak- shashila, the chief city in the eastern region of Gandhara. Originally, the Kahu-jo-daro stupa was decorated with 11 terracotta relief panels of seated Buddhas in the niches of the four faces of the platform. Each of the north, east and south faces had three large pan- els on either side of the entrance to the stupa from west side, it is explained. At the time of excavation only seven large images, and a small one, were found on site, it is reported. Kahu-jo-daro is probably the one site in the regi- on that has yielded so many relief panels of Buddha images so far. The CSMVS team began digital reconstruction of the lost stupa, which as Mukherjee explained, is one of the few examples of decorative terracot- ta stupa architecture in the Indus Valley. Utilising the collection at CSMVS, and some surviving architectural fragments, the task began of imagining reconstruc- tion of the original shape of the stupa, built probably in 500 CE, even though Sir Cousens assig- ned the stupa to c 400 CE, a cen- tury earlier. “One can easily imagine the magnificent scene around the stupa in the valley of Kahu-jo- daro,” he said, adding, “the main stupa with its majestic harmika stood nearly 20 metres tall, its towering presence inspiring devotees and pilgrims approa- ching from over a long distance. Thousands of local devotees, and those from all over India, perhaps even other countries, must have thronged here to pay their respects to the great soul whose corporeal remains were enshrined in the stupa.” The main entrance was em- bellished with decorative bricks and a torana or gate, as seen in Sanchi too. For pilgrims the cir- cumambulation or going round the stupa is a sacred ritual, fol- lowed in Hinduism and Jainism too. At Kahu-jo-daro the visual gallery of seated Buddhas, in niches of the platform walls before entering the stupa, was the source of piety, inspiration and austerity. Shrines inside the stupa would have contained images of the Buddha; it would seem these images were moved to another site, probably to ensure their safety from invasions before the entire stupa itself was covered in sand and left buried, forgotten for centuries. Kahu-jo-daro, as ‘The Lost Stupa’ details, belong- ed to a much earlier era; it could have been a reconstruction of a ruined stupa erected under Emperor Asoka’s orders in the 3rd century BCE. “In today’s time of peace and prosperity, preservation of cultural heritage has to become a top priority for UNESCO, gov- ernments of different countries and civil society too,” said Muk- herjee, emphasizing, “I strongly believe that the power of culture can change the world as it unites people, countries, religions, and customs. It works as a healing tool in our broken societies.” ‘The Lost Stupa’ is about finding and building everlasting peace.

The writer is researcher- writer on history and heritage issues and a former deputy curator of Pradhanmantri Sangrahalaya

Advertisement

Photos: CSVMS publication