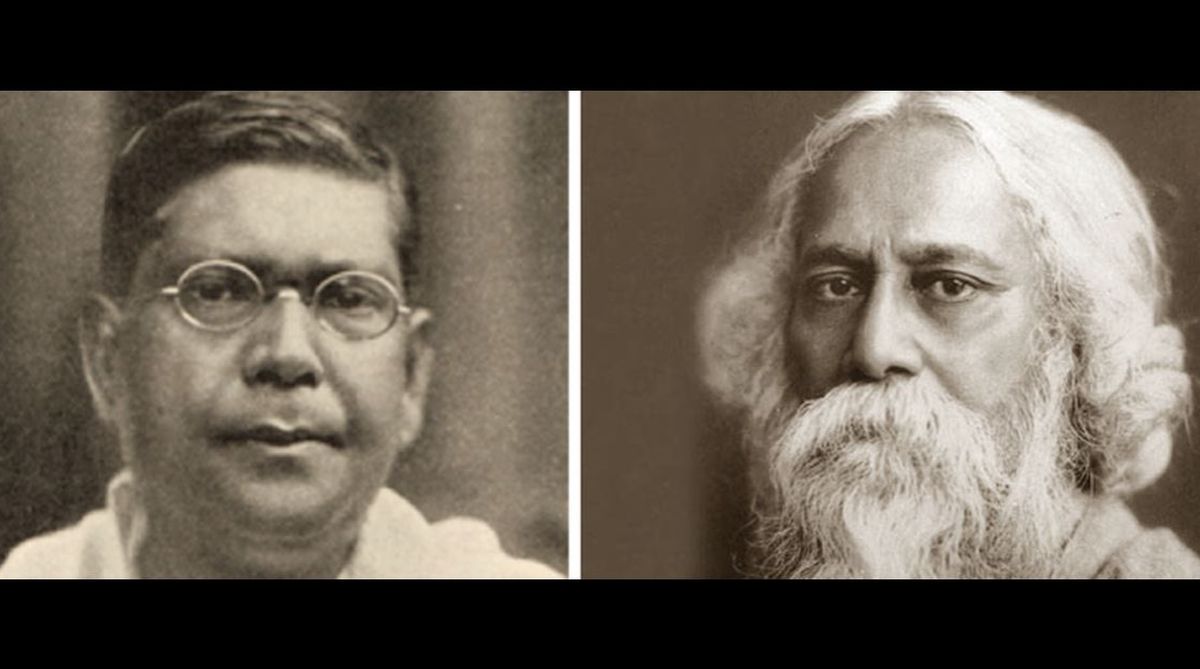

Chittaranjan Das (1870- 1925), known as Deshbandhu, was a noted freedom-fighter of Bengal. However, except for his early days, he was known to be a bitter critic of Rabindranath Tagore. He entered politics after the Swadeshi movement.

In Narayan, the magazine that he edited, Tagore was often criticised. Worthies like Bipin Chandra Pal (1858-1932), Suresh Chandra Samajpati (1870-1921), Girijashankar Roychoudhary, and Radhakamal Mukhopadhyaya (1889-1968) were relentless in their criticism of Tagore’s writings. Das was unhappy when the poet was knighted in 1915.

Advertisement

He first attacked Tagore in 1917 when he debunked his views on nationalism and internationalism. The essential thrust of his criticism was that Tagore in the swadeshi days, post-knighthood, had drastically altered his views, emphasizing more on internationalism and less on nationalism.

He remarked: “We stand then for freedom, because we claim the right to develop our own destiny along our own lines unembarrassed by what Western civilization has to teach us and unhampered by the institutions which the West has imposed on us. But here a voice interrupts me, the voice of Rabindranath, the poet of India”.

Das also quoted from Tagore to the effect that “the Western culture is standing at our door; must we be so inhospitable as to turn it, or ought we not to acknowledge that in the union of the cultures of the East and West is the salvation of the world”.

He then rejected it. He agreed with Tagore that India could not live in isolation and made two criticisms of the poet’s formulations: (1) to receive a guest one needs to have a house of one’s own, implying that such noble ideas would have to wait till India attained independence; and (2) India’s own cultural heritage ought to be on a firm pedestal before Western ones could be assimilated with the indigenous culture.

Das once again made a detailed criticism of Tagore in his presidential address at the 1922 Ahmedabad Congress. Since he was in prison the address was read out by Sarojini Naidu (1879- 1949). He appealed for a nationalist movement and criticized what he perceived to be the antinationalist streak in Tagore’s thoughts.

He raised a couple of issues in his essay: (1) There was an inherent right to develop independently without imbibing ideas and institutions of the Western civilization; (2) He even thought that Western institutions were imposed on India; and (3) Dealing with the issues raised by Tagore he quoted him thus, “The western culture is standing at our door; must we be so inhospitable as to turn it away, or ought we not to acknowledge that in the union of the cultures of the East and the West is the salvation of the world”.

Das linked political domination to the cultural one and stressed the need to resist the latter. “She must vibrate with national life; and then we may talk of union of the two civilizations”. On the charge of non-cooperation being a negative and not a positive feature, he again took up issue with Tagore. He clarified that the noncooperation movement did not prohibit contact or cooperation with the British. It neither supported separation nor isolation as a policy. Das perceived that the challenge was to mobilize a collective opposition to “forces of injustice and unrighteousness”.

He argued as he did earlier, that policies must have stages of growth, a notion that Walt Whitman Rostow (1916-2003) cogently developed after the Second World War, and Tagore’s ideal could wait till India developed further. Comparing nations with flowers, he advocated separatist cultures evolving and developing its future as that was the way different nations could make a meaningful contribution to the entire humankind. Each nation had its own distinctiveness and nations had to evolve logically and within this individualized framework. It was in this distinctiveness that the essence of nationalism had to be discovered.

Das, like Mahatma Gandhi, did not really answer the important questions raised by Tagore and without trying to seriously comprehend and reply to them, he took the easy way out of rhetoric rather than grounding his arguments on reason. He ignored the fact that Tagore was a firm supporter of the right of self-determination not only for India but for all the colonies. He did not reply to Tagore’s charge that many of the programmes of the non-cooperation movement like universal use of the spinning wheel and boycotting schools and colleges, the English language and the burning of foreign clothes were not taken up at all.

Das was initially opposed to the Non-cooperation Movement but subsequently joined it tactically. He deviated from Gandhi’s precepts while operating in Bengal. He was totally superficial in his criticism of Tagore. He ignored the latter’s lifelong hatred towards colonialism and did not have any inkling of his deeper study of Tagore’s political writings including his widely popular essays on nationalism.

Das, like Lokmanya Bal Gangadhar Tilak (1856-1920) was aware of the major contradictions in society but instead of devising a mechanism to tackle them, he believed in the politics of postponement without realizing that postponement would widen the divisions. Tagore understood and tried to work out the details of the factors behind India’s under-development and tried to work out solutions, pre-eminently the development of Santiniketan and Sriniketan… one complementing the other.

Gandhi, who had linked the charkha with swaraj during the non-cooperation movement moved away from such a simplistic and unworkable solution by accepting the 14-point constructive programmes in 1925 and began to concentrate on the social rather than the political issues for most of the time. This was an indirect acknowledgement of the correctitude of Tagore’s critique.

For Das, the greatest failure was to misunderstand the complexities of the Hindu-Muslim relationship and that his much-wanted Bengal Pact, which was based on enhanced job quotas for Muslims in Calcutta Corporation and one that was applauded by Maulana Azad (1888-1958), collapsed like a house of cards after his death.

Nation-building in a society of major contradictions required patience and painstaking exercises for a long time and as our nationalist leaders, unlike Tagore, concentrated only on elite accommodation and marriages of convenience, none of their programmes endured. It is a fact of history that by the time Gandhi launched his second most important movement, the salt satyagraha with more careful planning and involving a small number of satyagrahis, modelled after Vladimir Ulyanov Lenin’s professional revolutionaries, the Muslim alienation.

And this could not be reversed till Partition. Tagore in his memorial message at Das’s untimely death made a point which again brought out his differences with Gandhi. He commended Das for his “creative force of a great aspiration” and the realization of that need not by “any particular political or social programme”.

Das deviated from many accepted principles of Gandhi and against his wish, he also founded the Swarajist Party after the collapse of the non-cooperation movement. A virulent critic of Tagore, Das received the latter’s praise for his capacity of individual judgment and courage of action, qualities that Tagore valued the most.

When Gandhi withdrew the non-cooperation movement, Das wrote that the Mahatma opened a campaign in a brilliant fashion, and worked with unerring skill till he reached the zenith of the campaign, but after that he lost his nerve and began to falter. The tirade against Tagore continued. It was because of this superficial understanding that Semanti Ghose observed that the “political legacy of Chittaranjan Das was short-lived”.

The writer is former Professor of Political Science, Delhi University.