Trust deficit remains in India-China ties

An agreement on resolving the standoff in Ladakh was reached on 21 October, just prior to the Brics summit in Kazan, Russia, paving the way for a Narendra Modi-Xi Jinping dialogue at the venue.

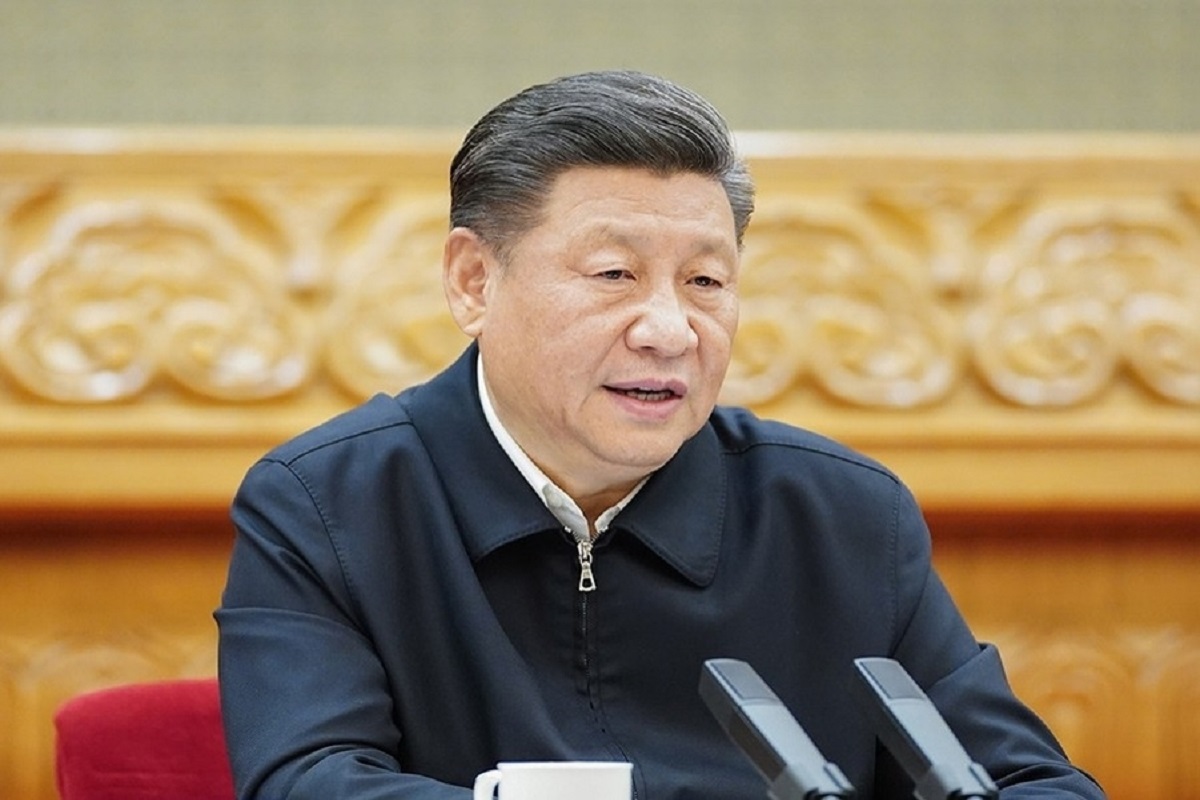

Chinese President Xi Jinping (Photo: IANS)

Conspiracy theories are seemingly circulating at the speed of sound in the wake of the unprecedented changes wrought by Chinese President Xi Jinping in the upper echelons of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) earlier this week. The facts are as follows. Top officers of the PLA’s Rocket Force, responsible for overseeing China’s nuclear and conventional missile forces, have literally vanished from public view.

Among those unaccounted for is Mr Li Yuchao, commander of the PLA Rocket Force, who was conspicuously absent from Mr Xi’s recent promotion of senior generals. A Canadian consultancy firm which specialises in tracking China’s power elite has flagged ten current and former Rocket Force officers whose status remains unclear, including Mr Li and his deputy Mr Liu Guangbin. The South China Morning Post has reported that several serving and former Rocket Force officers are being probed for graft and/or indiscipline. What these developments tell us about the state of the party-state under Mr Xi has two aspects. First, the disappearances exhibit that the Chinese President, clearly his country’s most powerful leader since Mao Zedong, retains substantial political heft despite murmurs of disenchantment within the Chinese Communist Party (CPC) at his clique-centric policymaking process, autocratic manner of functioning and, in the economic, public health, and foreign policy domains, many rather inexplicable decisions. Indeed, some commentators have gone as far as to say that the sweeping, overnight changes he has initiated in the most powerful organ of the CPC, the PLA, are reminiscent of the ‘Great Leap Forward’ years, if not in scale at least in intent. But the flip side is that these regular purges in the silos that comprise the communist state apparatus are also an indication that his over a decade long reign, which has been marked by a concerted effort to establish personal loyalty of the armed forces to himself and exert complete control over senior officers, has not been successful. That, it is argued by observers, is precisely why they continue. Of course, these decisions have been dressed up as a cleansing of the system.

Advertisement

At recent high-level meetings held in Beijing, Mr Xi conveyed what a media report described as a “strong message” to military leaders, stressing the necessity to address the persisting issues related to party organisations’ enforcement of absolute leadership over the military at all levels. It is in this context that last week’s abrupt removal of the President’s hand-picked Foreign Minister Qin Gang from his post needs to be seen. To underline the messaging, the Central Military Commission, chaired by Mr Xi himself, has called for the establishment of an “early warning mechanism for integrity risks in the military” while launching an investigation into corruption in equipment procurement going back over five years. The last word on the issue is yet to be heard but one thing is certain: China rests uneasy. That is not good news for either the country’s allies or its adversaries because it provides a fertile ground for bad decisions.

Advertisement

Advertisement