Thousands of people, adorning the colours of the women’s suffrage movement ~ green, purple and white ~ marched in England, Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales on 10 June with the banner, ‘We have the vote, Now, we want equality’. They were commemorating the 100th anniversary of women securing the right to vote (1918) .

Till then, women were politically invisible and the political domain was dominated by men alone. Even propertied women were not considered eligible for vote as women were not legal persons: their wages, inheritance, jewellery and money belonged to their fathers and husbands. The husband voted on behalf of his wife as a married couple is “one” in the perspective of the law.

Advertisement

New Zealand was the first country to grant the right to vote to women, but it was in Britain that there was an intense debate about women’s nature, role and status in society, marriage and femininity. It challenged the notion of separate spheres that industrialization had brought about, cutting across party lines and ideological positions with supporters and opponents in every party and within every ideology.

The first Women’s Petition, drafted by Katherine Chidley, Elizabeth Lilbrune and Mary Overton was presented to Parliament in 1649. It questioned patriarchy. In 1792, Mary Wollstonecraft and some radical dissenters recommended representation for women but shelved it as it would evoke sarcasm. In 1832, prior to the passage of first Reform Act that provided the voting right to propertied men, Mary Smith presented the first women’s suffrage petition to Parliament.

Despite the ascendancy of Queen Victoria to the throne in 1837, women did not get the right to vote, as she opposed women’s suffrage and their admission to universities. In 1847, the first women’s suffrage bill came up in the House of Commons. In 1848, Disraeli speaking in the Commons, questioned women’s exclusion from suffrage.

Education, rapid industrialization and women’s employment enabled women to organize themselves and campaign intensely for securing the right to vote. The first women’s suffrage organization was the Sheffield Female Political Association, which was founded by Anne Knight in 1851. In 1866, John Stuart Mill presented a petition for women’s suffrage in the Commons but it was rejected.

Edward Kent Karslake, a Tory MP from Golchester, remarked that he had not met a single woman in Essex who was in favour of women’s suffrage. Despite 129 women signing the petition to the contrary, only 73 MPs lent support, while 196 opposed Mill’s proposal. As a result of the failure, the National Society for Women’s Suffrage with Mill as president was formed in order to disseminate information throughout England on the issue.

In the aftermath of the 1867 Reform Bill, suffrage societies were formed in Edinburgh, London and Manchester. In 1881, the Isle of Man granted voting rights to its women. In 1884, the third Reform Bill was passed, enfranchising a section of the working class… but not women.

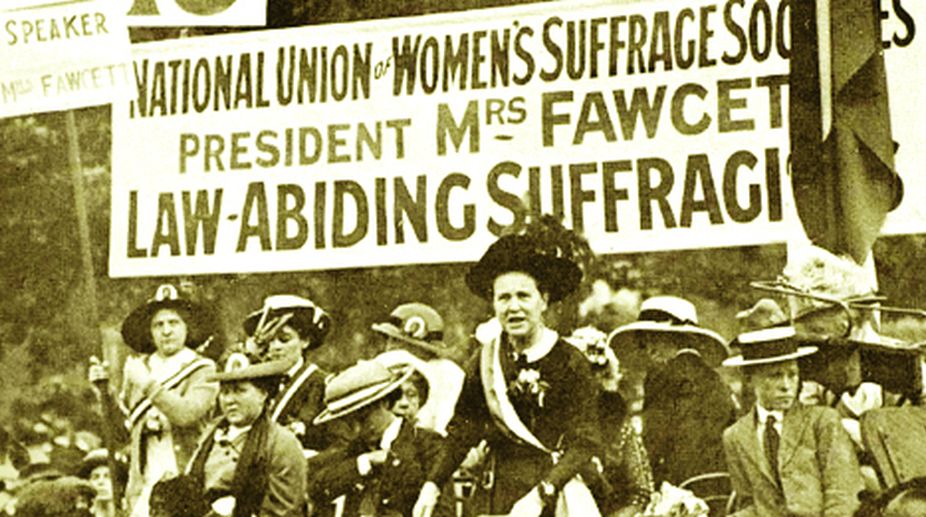

In 1897, the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies (NUWSS) was formed with the support of 20 national societies under Millicent Fawcett’s leadership. It was committed to ‘constitutional agitation’ through lobbying, petitions and letters to Parliament in order to secure the vote for women.

Frustrated with the NUWSS’ ‘wait and watch’ tactics, Emmeline Pankhurst and her two daughters ~ Christabel and Sylvia ~ split and formed the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) in 1903. Their methods are were militant, almost similar to that of the Russian radicals.

Their slogans were ‘deeds not words’ and ‘Votes for Women’. The latter was also the name of their newspaper which sold 40,000 copies each week. The rift between the NUWSS and WSPU became open with the former continuing with petitions and the latter with protests. They were described as the ‘Suffragettes’ by Charles Hand of the Daily Mail in 1909.

Fawcett and her followers were the ‘Suffragists’. The WSPU later split in 1907 rejecting the dominance of the Pankhursts. The breakaway group, the Women’s Freedom League (WFL) emerged with its paper, The Vote and was committed to non-violence and such measures as non-payment of taxes and non-completion of census forms.

Fawcett described the NUWSS’ methods as the ‘spirit of order’ and that of WSPU as the ‘spirit of audacity’. Together they ensured success to the cause

The women’s struggle for suffrage, for equality, their ‘Cause’ that began in the 1850s continued till women secured the vote, which for them was their single, simple and overarching aim though they cares for many other causes such

as admission to universities, access to professions and sexual double standards. In their reckoning, they were “hedgehogs but foxes in their causes”.

As Arblaster observed, “The vote was crucial to improving the status and conditions of women which they believed would be achieved as a result of women’s enfranchisement”. This is contrary to contemporary women’s movement that lacks a “specific issue that supersedes all others, within countries, let alone between them”, writes The Economist.

There are several reasons why women secured the vote in 1918: (1) the first working class revolution in Russia in 1917 and the shockwaves it released in the rest of Europe; (2) women’s contribution towards the war effort and as Joll observed, “their obvious ability to do jobs hitherto regarded as men’s work made a telling argument”. (3) Changes without disrupting a basic sense of continuity in the British political process namely the gradual widening of suffrage through the Reform Acts of 1832, 1867 and 1884 and the electoral changes particularly between 1883 and 1885 that brought in members from the middle class and professionals and first-time working class constituencies.

The debate and the struggle for women’s suffrage at one level unified and projected a collective identity ~ that of ‘women’. But simultaneously it brought out the contradictions within each gender, between genders, between gender and class and, between gender and race in a social order that was highly stratified and differentiated.

Feminists, since then continue to wrestle with these contradictions. In this centenary year of the British women receiving the right to vote, both the suffragists and the suffragettes deserve salutation as their struggles remind us, in the words of Ralph Miliband, that “rights are never given but are earned”.

The writer is Associate Professor in Political Science, Jesus and Mary College, New Delhi