India’s top 500 pvt cos value more than total GDP: Report

These companies value higher than the GDP of India and the combined GDPs of UAE, Indonesia, and Spain.

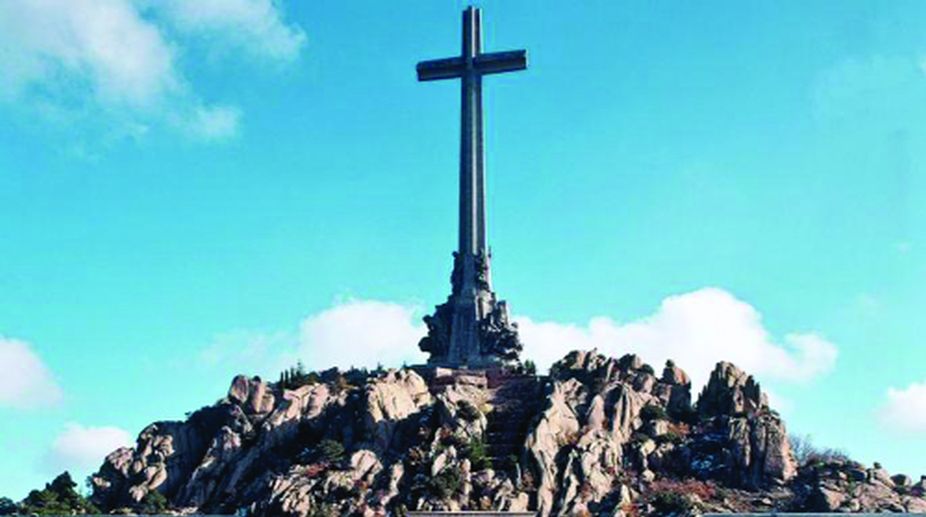

Valle de los Caídos.

Heading north on the motorway, leaving behind Madrid, as the terrain changes to mountainous, one can’t help but notice at a distance a 150-metre tall grey cross towering above the lush green mountain on your left.

This cross built by the prisoners of war during Spain’s civil war marks the tomb where Spain’s dictator Francisco Franco is interred in what is called El Valle de los Caidos or the Valley of the Fallen. A Reuters report said Franco himself inaugurated this monument in 1959. He died in 1975

Advertisement

The Valley of the Fallen is thus named because it also contains the unmarked graves of reportedly tens of thousands of (mostly) Republicans who were killed fighting the fascists during the civil war and whose bodies were brought here and buried without the permission of their families.

Advertisement

The process of healing of the wounds inflicted on the Spaniards by the dictatorship that ended with Franco’s death was so gradual and done so super-cautiously that the boat was not rocked; the constituency he had in the military and the security apparatus meant that many of the dictatorship cronies and beneficiaries were left untouched.

The party that was dislodged from power through a vote of no-confidence last month, the right-wing Partido Popular or PP, though officially may have distanced itself from Franco’s policies at least in terms of its public posture in the 21st century, was vehemently opposed to moving Franco’s remains from the monument.

Now Spain’s new socialist Prime Minister Pedro Sanchez has said that the dictator’s remains at the state-funded monument will be exhumed and handed over to his family. Pedro Sanchez also said that the remains of the Republicans will be identified and handed over to their heirs.

The 43 years since Franco’s passing have seen a number of tenures of left-leaning socialist governments in office but perhaps earlier the dictator’s legacy was far too fresh to be shunned with such a public statement.

Mr Sanchez’s Socialist Party has a mere 84 seats in the 350-seat parliament and rules via the support of a number of smaller parties ranging from the leftist Podemos and Izquierda Unida to the right-leaning Basque and Catalan nationalists, among others.

But it is clear the prime minister or the presidente del gobierno as he is called in Spain is taking strength from a series of massive corruption scandals, leading to convictions and imprisonment of both elected and unelected PP officials across the country.

The PP is visibly wounded and a party that has a tradition of accepting the leadership nominee of the outgoing leader to replace him has now got six candidates in the run to replace party leader and recently ousted prime minister Mariano Rajoy who refused to nominate his successor.

The track record of the Socialists themselves is not blemish-free in terms of corruption and the seeking and dishing out favours from/to the corporate sector. But the scale of the PP’s financial scandals speaks of the culture of impunity that existed in the party and reflected a hangover of no accountability from Franco’s period.

Despite his fragile government, Pedro Sanchez has been clear that he intends to govern till fresh elections are scheduled in about two years’ time. He also said after the planned removal of Franco’s remains, El Valle de los Caidos would be converted to a monument to reconciliation.

The country’s new leader is also moving to address the prickly Catalan independence issue and, as a gesture of goodwill, has ordered all those Catalan leaders who were jailed for making a unilateral declaration of independence and packed off to prisons hundreds of kilometres away from their home and, in cases, very young families shifted back to facilities close to their homes in Catalonia.

Given that he lacks an outright majority to make huge concessions to the Catalans it remains to be seen how he deals with the challenge. It is clear to most in Spain that Catalan independence is not an option but, short of that, some work seems to be under way to examine what acceptable solutions there can be.

But his desire to provide leadership, despite all his political vulnerabilities, and to address some basic issues of import to the ordinary Spaniard are being well received in the country, with criticism mostly coming from an angry and frustrated PP which has accused him of talking to traitors and those who want to break up the country.

This last fact must be reassuring to many Pakistanis. We aren’t the only ones who describe difference of opinion as treason and advocate the muzzling of voices of reason. Spain, sadly, suffered under a brutal dictatorship well into the 1970s while the rest of the countries in Western Europe had been transformed into vibrant democracies.

This primarily happened because, with the rise of the Soviet bloc after the Second World War, the West decided to look the other way rather than topple Franco and risk a leftist government elected to power. After all, Spain had an elected Republican government as far back as the 1930s which Franco deposed after a bloody civil war in 1939.

Pedro Sanchez’s desire today to have a monument to reconciliation must also strike a chord with Pakistanis. We also need a national reconciliation and decide once and for all after an open debate what kind of society we want.

For a country with a burgeoning population, water and power shortages and an economy that represents in perpetuity a seesaw ride and a dismal state of education, how long can we have state institutions acting in transgression of their constitutionally defined role with the impunity they became accustomed to under dictatorship?

This state of play is not viable in this day and age. The sooner we understand this the less pain we’ll inflict on ourselves and our country.

Dawn/ANN.

Advertisement